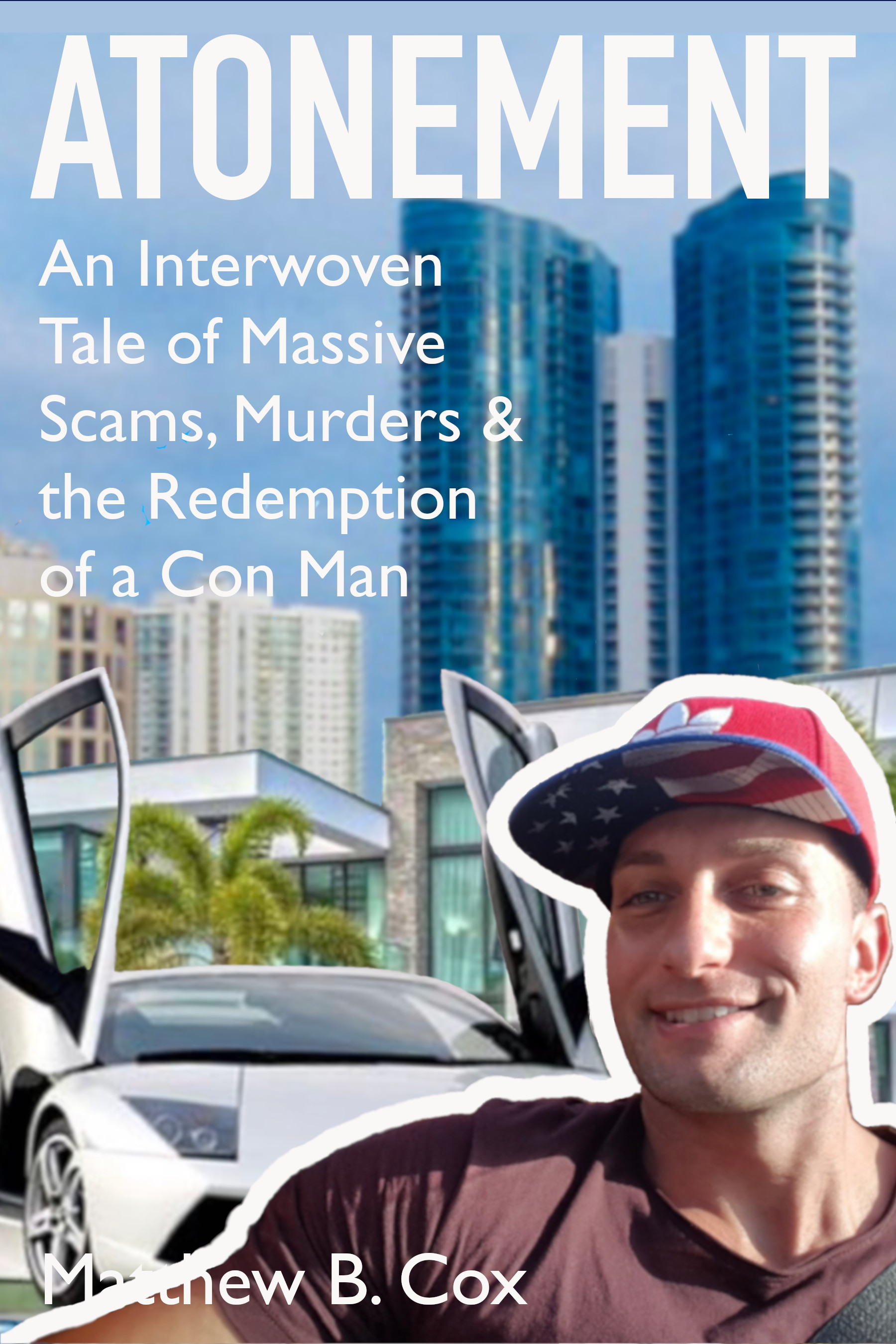

By Matthew B. Cox

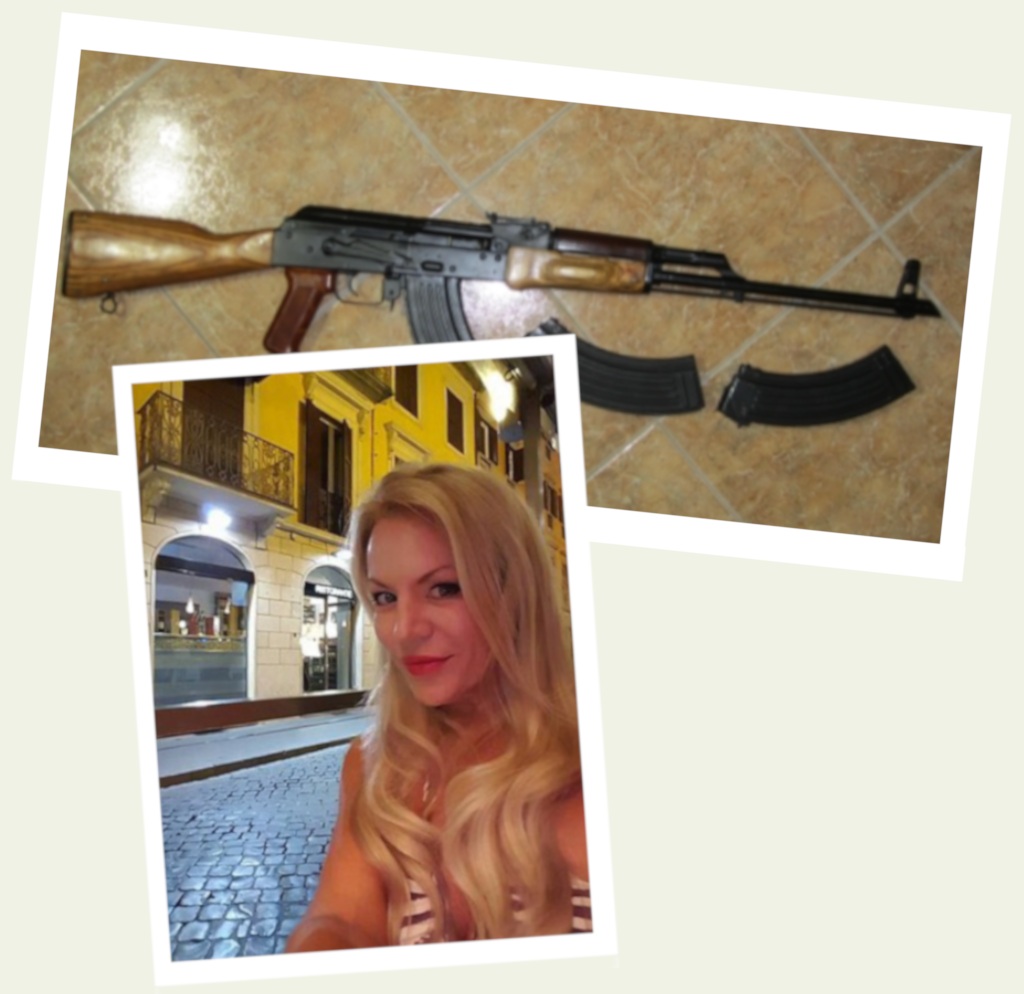

THE AK-47 CRACKED, sending a 7.62 projectile spiraling down the assault rifle’s barrel. It briefly traveled through the air, then plunged into the attractive forty-two-year-old blonde’s chest. The round blew a dime-sized hole in her ribcage as it spiraled through the woman’s upper-torso and tore out of her back, leaving a silver-dollar size exit wound—hours later, forensic examiners with Broward County would locate the mangled bullet lodged in the baseboard.

The blonde immediately dropped to the living room floor. None of the neighbors in south Florida’s exclusive Plantation subdivision heard the shot, or at least they didn’t report it.

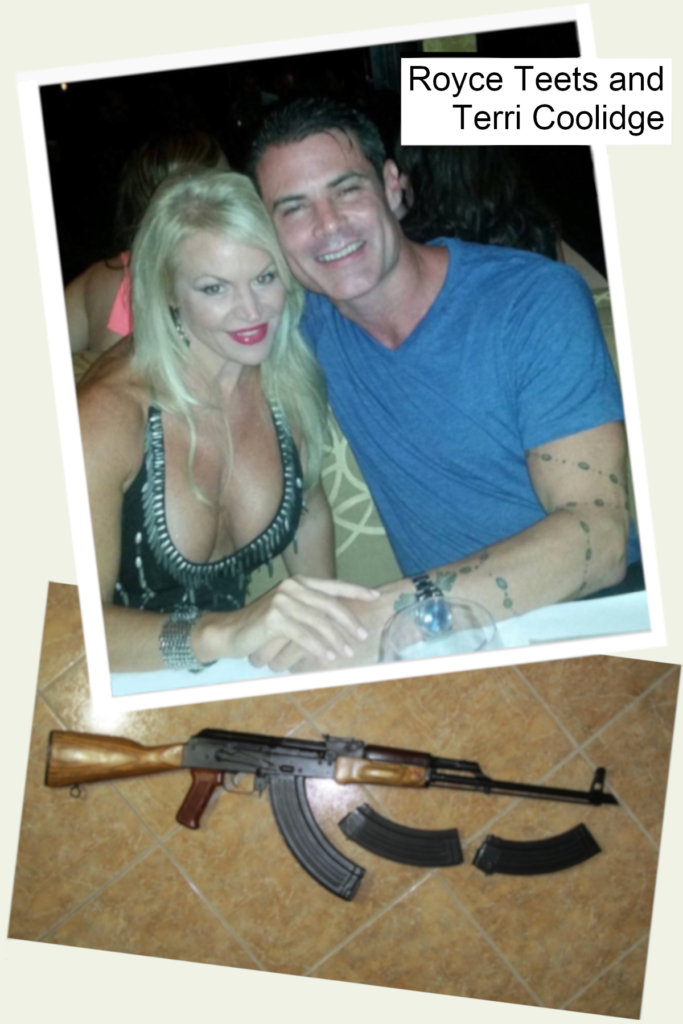

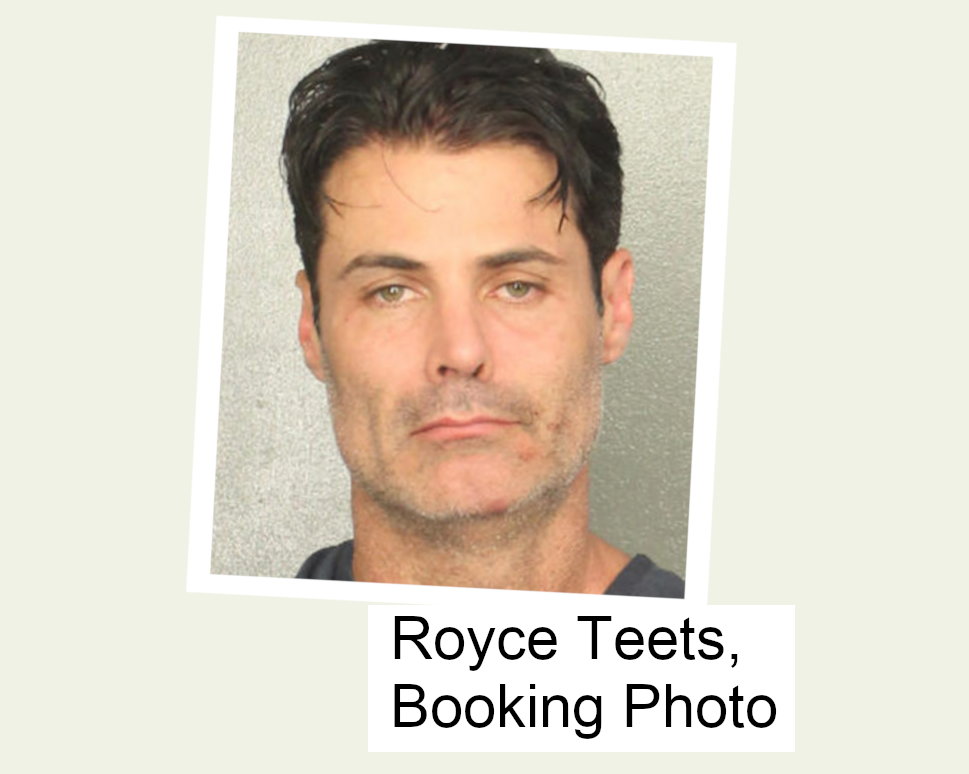

Terri Coolidge’s lifeless body lied in an ever increasing pool of blood on the wood floor as her fiancé, forty-six-year-old Royce Teets stared down at her. The smoldering assault rifle, clutched tight in his palms. Her eyes gazed into the abyss.

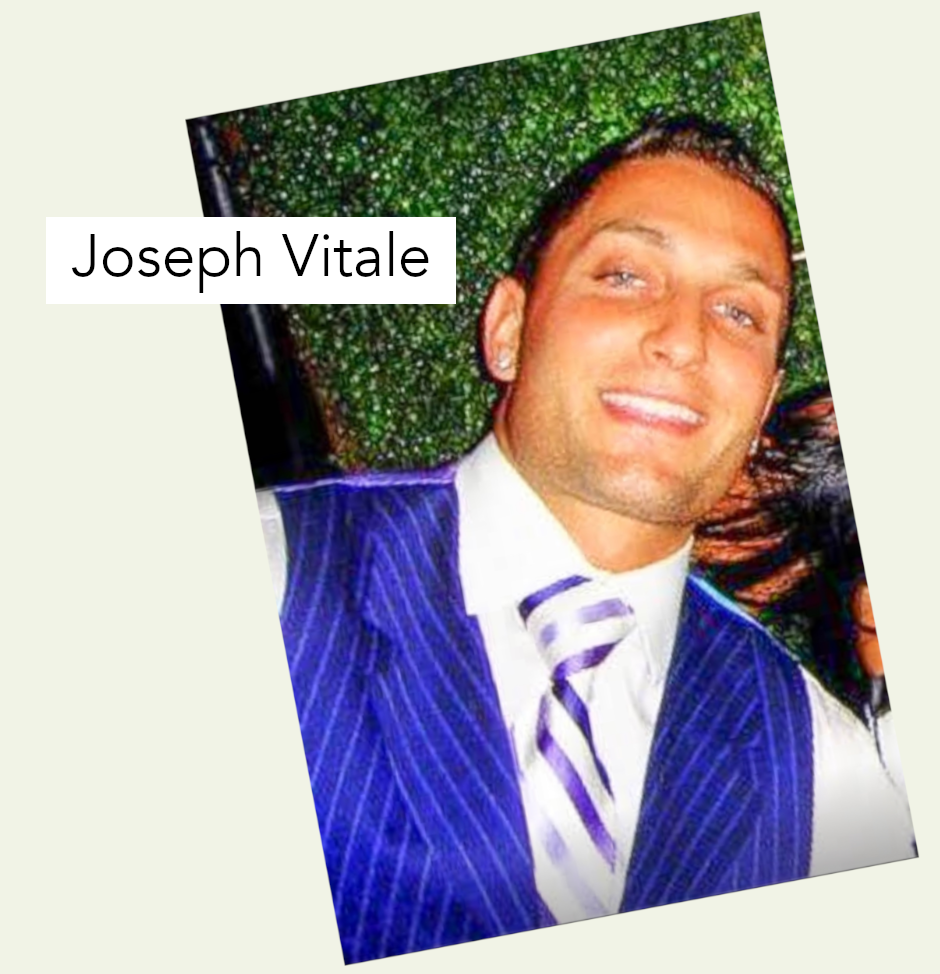

Why Royce, a seemingly-successful stock broker, killed Terri Coolidge on July 10, 2016, is debatable. According to the police report, the couple had been arguing for several hours regarding Royce’s drug addiction and infidelity. However, there is another explanation which the authorities failed to address. Specifically, Royce planned on killing his business partner, Joseph Vitale. A decision that Terri, due to her friendship with Vitale, was no doubt opposed to.

As Terri’s body lie motionless on the floor, Royce’s cell rang. Vitale was minutes away.

“Do me a favor,” Royce said into the receiver. “Meet me in the back, at the dock.” But Vitale wanted to come in and say hello to Terri. He had pictures of his Fourth of July shenanigans that she just had to see. “She’s sleeping,” Royce retorted, looking down at his former-fiancée. “Don’t come to the front door. Walk around back to the dock.”

The request struck Vitale as odd. The partners’ relationship had grown strained. In fact, weeks earlier, a mutual friend had confided that Royce was openly talking about having Vitale murdered. At the time, he hadn’t taken the threat seriously. Now, however, at ten o’clock on a Sunday night, Royce was making odd requests to meet him at a secluded dock.

“I don’t know Royce,” replied Vitale wearily; turning his Ferrari California into the subdivision, “something’s not right.”

“Bro!” spat Royce. “Just meet me around back.” Vitale could hear the desperation in his partner’s voice as he swore, “I’d never hurt you. Terri loves you, you’re like family.”

Whoa, whoa, thought Vitale. Who said anything about hurting me?

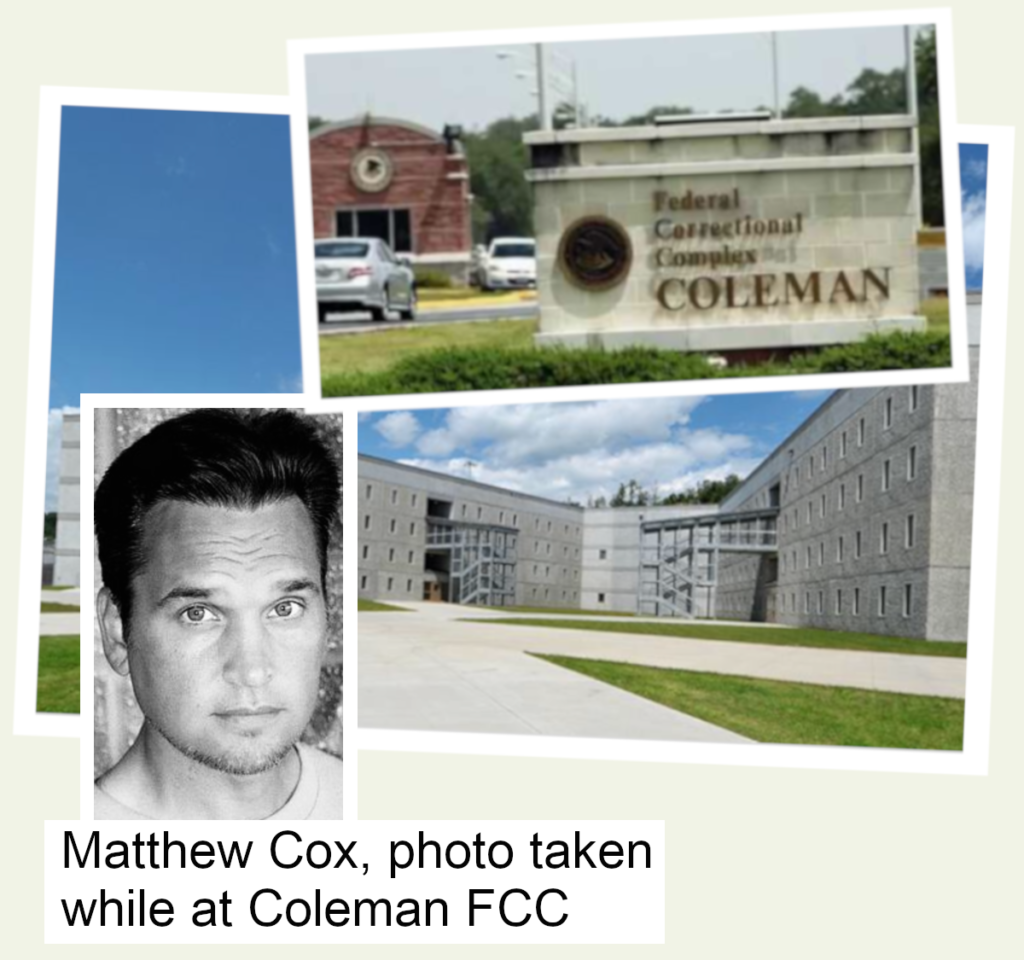

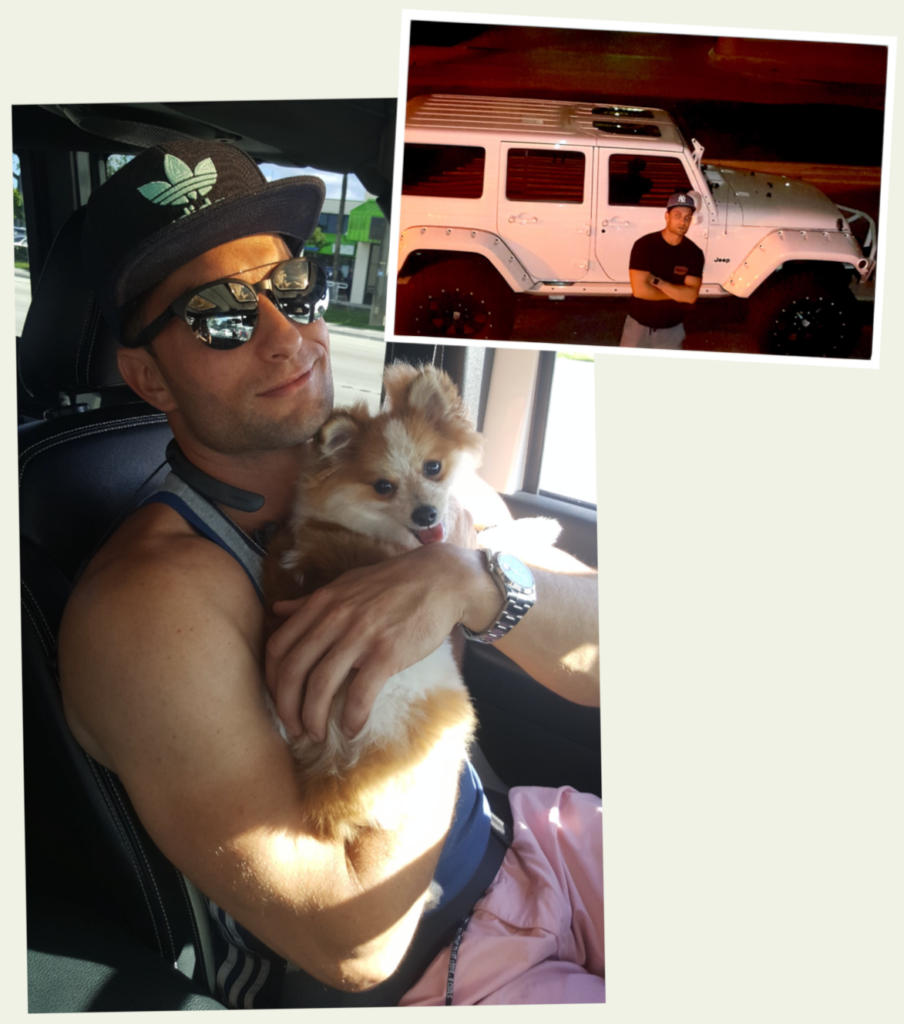

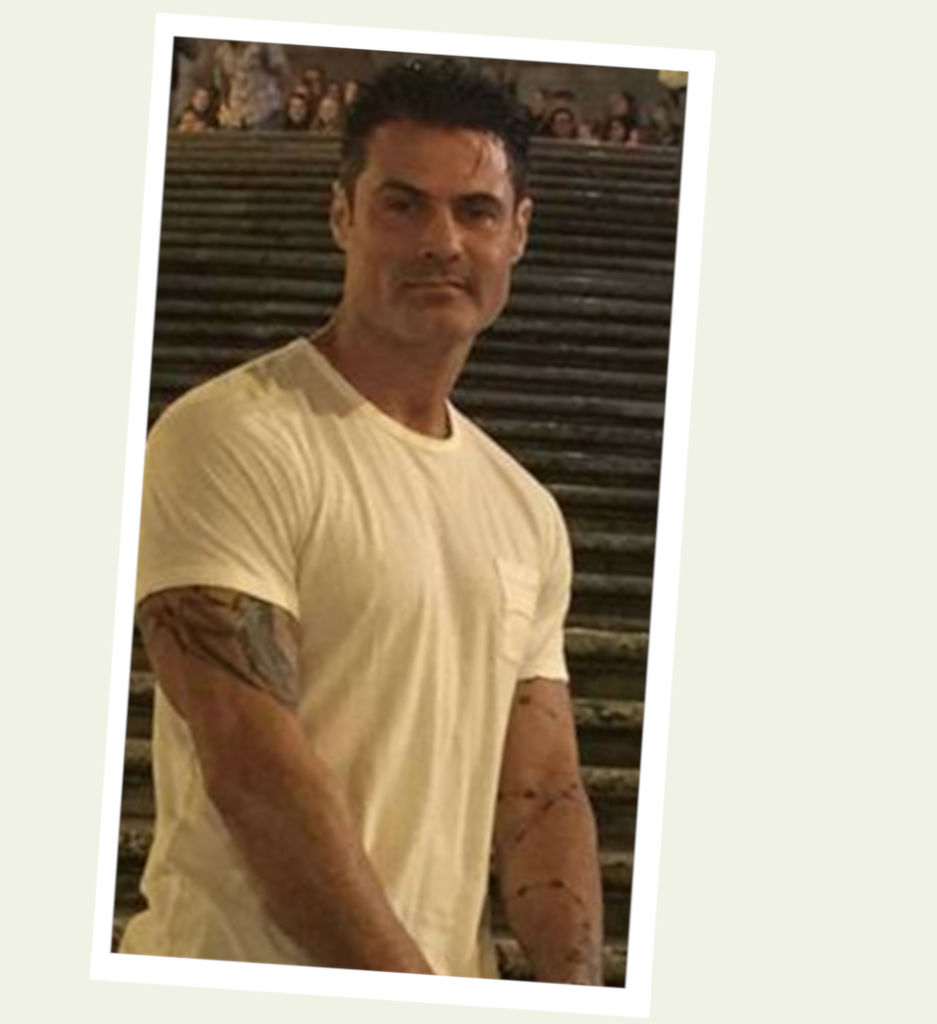

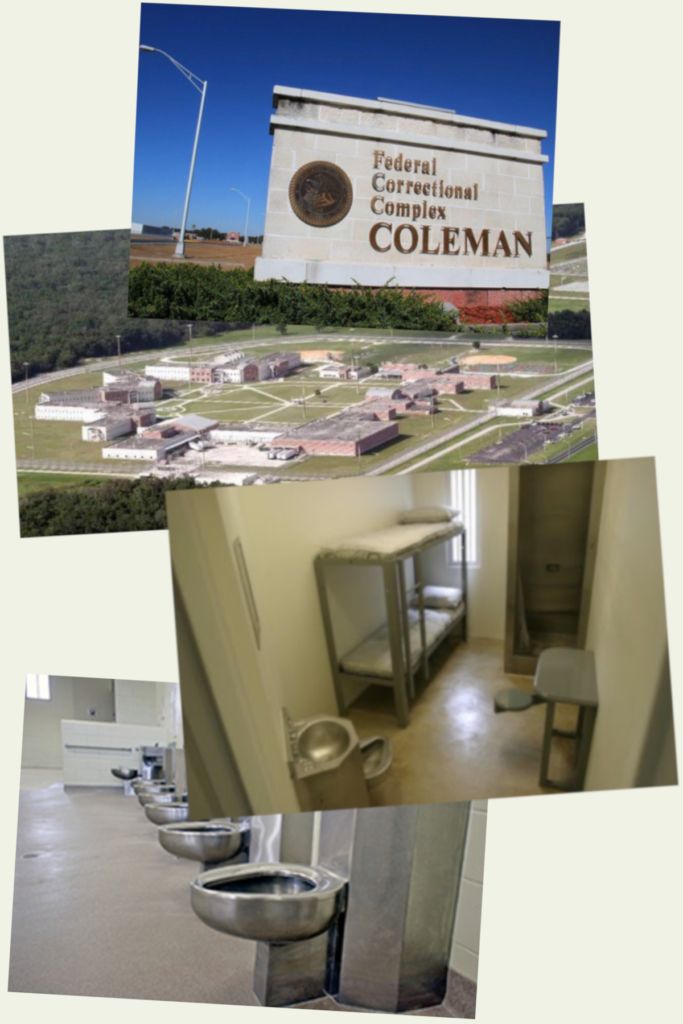

I FIRST NOTICE JOSEPH VITALE when he takes the seat next to me. It’s Monday, March 26, 2018, our first day of the Residential Drug Abuse Program at the low security prison in the Coleman Federal Correctional Complex in central Florida. I should probably mention that both Vitale and I are federal inmates—con men, according to our respective prosecutors. As a part of Vitale’s sentence he’s required to enroll in a drug treatment program. For good reason, admittedly, he has a drug and alcohol problem. Vitale is unquestionably handsome. At thirty-two, the American-Italian has short dirty blond hair, blue eyes and the chiseled Romanesque features of a battle hardened legionnaire—an Italian Chris Evans. He is in such good shape, in fact, I notice he somehow makes our typically unruly prison issued hunter green uniform look stylish.

While myself and the twenty other participants share our personal struggles with addiction and criminal behavior, over the next few weeks, I pick up that Vitale—a transplant from Long Island, New York—is charismatic and self assured as well as gregarious.

Over lunch in the cafeteria, sometime in late-April, I mention to him that I’ve spent the last few years of my incarceration writing our fellow prisoners’ true crime stories. I tell Vitale I’m currently working on an exposé entitled Devil Exposed. “It involves a double-murder.” I glean a hint of something in his eye. Not curiosity or intrigue, but something darker, and I inquire, “You okay?”

“A friend of mine was murdered,” he says. I’ve heard bits and pieces of Vitale’s criminal history; he’s a non-violent offender incarcerated for fraud. “They said it was an accidental overdose, but I know he was murdered.”

“How do you know?”

Vitale glances up from his tray, his expression void of emotion, his gaze empty, and he confides, “Because I met the piece of shit that killed him.”

ISAAC GROSSMAN’S SILVER LAMBORGHINI Gallardo was sitting in the parking lot of an upscale restaurant in Ft. Lauderdale, Florida, when Vitale and his girlfriend, Alicia Puglice, arrived. It was summer 2005, and they were late for their double-date with Alicia’s friend, Erica, and Grossman, the guy she was seeing.

He seemed like a nice enough guy, Vitale thought. A professional-type, in his early-thirties that had the swagger of a man who had the world by the balls. Grossman was not only wearing an exquisite suit, but he was sporting Erica. Despite his wife and children, Grossman had been keeping her as his mistress for nearly a year.

Grossman bought lots of drinks, and, as they finished dessert he invited everyone to Auto Slims, a trendy downtown club.

Vitale and Alicia were headed to the parking lot in search of his aging Volkswagen Passat, as the valet pulled to a stop in Grossman’s Lambo.

The twenty-year-old Vitale, distinctly recalls gawking at the over-the-top, high-gloss, black rimmed, heart pounding Italian bull, thinking, I want this guy’s life. “Nice car,” was all he managed to say as Grossman helped Eric in. Vitale felt like a child, but he had to know. “What do you do?”

“I’m a stock broker.”

That night, while the girls were in the restroom, Grossman bragged that he made a hundred grand on a bad month. Vitale, who’d moved south months earlier to pursue a degree in Graphic Design from Florida Atlantic University, and was struggling financially, enquired how he could acquire a Lambo. The broker gave him the once over, sized him up, and said, “I gotta see if you’ve got what it takes first.” Grossman handed the starving artist a business card and added, “Call me next week.”

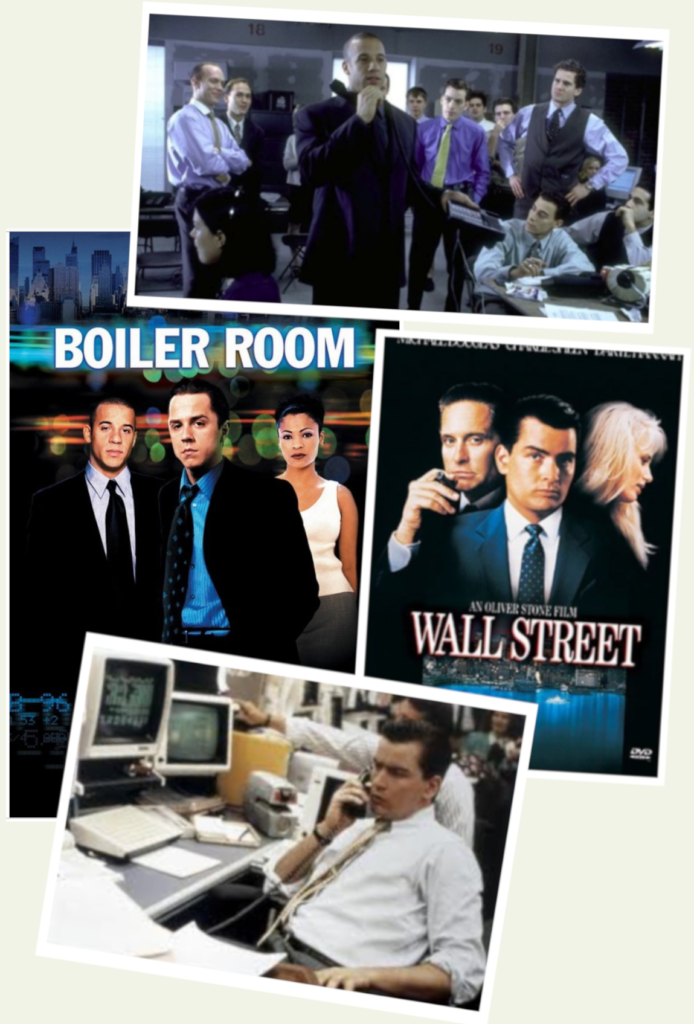

Monday afternoon Vitale was seated across the desk from Grossman at the brokerage firm of Emmett A. Larkin. He’d toured the office and seen the brokers—young, good looking guys just like him—in their crisp suits chattering into headsets. Making pitches and closing deals. Vitale thought it looked like a scene out of the movie Wall Street or Boiler Room. Big money was being made, Vitale could see that, and he wanted in.

Grossman went over the firm’s training program. “You’ll be paid two hundred dollars per week; and you’ll call prospective clients under my license.” Once Vitale opened fifty accounts for the firm, they would schedule his Series 7. “If you pass, we’ll give you twenty of the accounts back.”

“When do I start?”

“Right now.”

VITALE’S MOTHER AND FATHER were furious. “My dad’s a super conservative Italian-immigrant,” admits Vitale. His parents had hoped their son would get a college degree in a safe, secure industry and get a stable job. “He wasn’t all that thrilled about the Graphic Design degree; you can imagine how he felt about me ditching school to be a broker.” Specifically, according to Vitale, his father warned that if he dropped out of FAU, he’d cut him off financially. “He said, ‘You do this and you’re on your own.’—”

“You quit anyway?” I interject.

Agitated, Vitale throws his hands in the air. “Grossman was driving a Lamborghini—a fuckin’ Lamborghini!”

THERE ARE TWO PARTS of the stock brokerage business. One, acquiring new clients or “new accounts.” This requires cold calling leads—potential customers—and pitching them on investing with the firm. If they seem remotely interested, the potential client is handed off to a broker who persuades the potential client to open an account for whatever amount they can squeeze out of the firm’s new client. Step two, necessitates the account to be managed by a broker or “trader.” Stocks had to be evaluated. Companies and trends had to be studied as potential investments.

“I’M DEALING WITH TOO MANY brokers as it is,” sighed Vitale’s potential client. It was Vitale’s first day on working the phones and he’d just recommended one thousand shares of Porta Player, a manufacturer of semiconductors. “I can’t do it.”

Over the last week he’d sat and listened to several brokers call leads. Vitale had picked up bits and pieces of the business, he’d memorized the script, and multiple rebuttals. However, he was only supposed to be making “soft inquiries” as to potential clients’ interest in opening an account with the firm, not “hard closes” on particular stocks.

“You’ve got too many brokers, because you haven’t found the right one!” pounced Vitale, repeating a rebuttal he’d heard a senior broker use. “I work with three hundred and fifty clients that I’ve cherry picked in forty-eight states, including the senior vice president of Hewlett Packard, Randy Mott, and Guy Harrison with IBM. I’m the guy that can make you money day in and day out, again and again.”

“Okay, okay,” interrupted the potential client, “I’ll do five hundred shares.”

That was the unlicensed trainees first new account and sale. Typical trainees take over six months to open the required fifty new accounts. Vitale did it in three weeks.

“Grossman and his partners thought I was a rain maker,” admits Vitale during one of our many discussions, which eventually turned into interviews for his true crime.”But the other brokers; the other brokers started hating me. I was opening two, sometimes three accounts a day—one day I did twelve. The other guys despised me.”

He passed his Series 7 exam in early-2006, allowing him to solicit business under his own name, trade stocks, bonds, and options. Shortly thereafter, he obtained his Series 63 giving him the ability to work in every state.

Vitale could see the commissions being generated based on the accounts he’d handed off to Grossman and his partners. “They never gave me the twenty accounts they’d promised,” he says. According to Vitale, part of the firm’s business model was to screw their trainees out of their accounts. “It’s a brutal industry, but I didn’t complain. I was just trying to hang on until I could build up a book of business.”

“How were you paying your bills?”

“I wasn’t,” he admits. By the time he’d obtained his licenses, Vitale had been evicted from his apartment. “Alicia had gone back to New York. I was living out of my car and showering at LA Fitness, but it didn’t matter, ’cause I knew I’d found an industry where I could excel.”

Then, the bottom fell out. Erica—Grossman’s mistress—called his wife and sent her pictures of she and Grossman having sex. The marriage began to deteriorate, as well as Grossman’s relationship with his business partners.

“These guys, and their wives, were all friends,” says Vitale. They wanted Grossman to stop seeing Erica or resign from the firm. The affair tore his world apart; and because Vitale was Grossman’s protégé, his employment at the firm became tenuous.

THE SUPPLE LEATHER CHAIRS, Mahogany table, and expensive commercial carpet in the conference room at InterCap Wealth Management radiated blue chip stability; even if the brokers occupying the chamber didn’t.

“Quarter of a million,” snapped Grossman at InterCap’s regional manager. “You get me, Mr. Vitale (he motioned to Vitale seated beside him at the conference table), and our entire book of business.”

“We’re willing to do one hundred and seventy-five,” he replied. It was a solid signing bonus, and Vitale was ready to take it, but Grossman continued to push for the $250,000.

He’d agreed to split everything fifty-fifty with Vitale if he’d abandon Emmett Larkin. Grossman moved him into his new bachelor pad, however, Vitale was still struggling financially.

“Can’t do it,” retorted Grossman. He assured the manager their book contained several hundred accounts—wealthy clients that trusted them implicitly. The statement was nowhere near accurate, but Vitale remained stone faced. “We’ll make you double that in the first quarter.” Grossman sighed in frustration and added, “This is starting to feel like a waste of time.”

“Two hundred thousand,” growled the manager. He leaned forward and extended his hand. “Two hundred thousand dollars and you and Mr. Vitale start tomorrow.”

Grossman smiled, stood, and the two shook hands. Vitale had just made his first $100,000.

They started calling their clients and persuading them to move their accounts to InterCap. Vitale opened nearly fifteen accounts the first day; by the end of the first month they had made $114,000 in commissions.

Unfortunately, due to Grossman’s cocaine addiction, coupled with his inability to keep appointments, cracks began to show. Within several months Grossman and InterCap’s manager got into a massive argument. This led to he and Vitale quitting.

They moved to I-Trade Direct, but were thrown out after two months; once again, due to Grossman’s erratic behavior. This time they landed positions with the firm of J.P. Turner; a boiler room swimming with alpha males. Hard closing adrenaline junkies, cold calling bad leads, sixty to seventy hours a week. Vitale gave Grossman a stiff lecture. “Cut the shit, bro,” he told him. “This is the last time I’m following you anywhere.”

“I got it,” agreed Grossman. He gave him some half assed excuse and assured Vitale, “I’ve been having a hard time, but I’m back, bro. I’m back.”

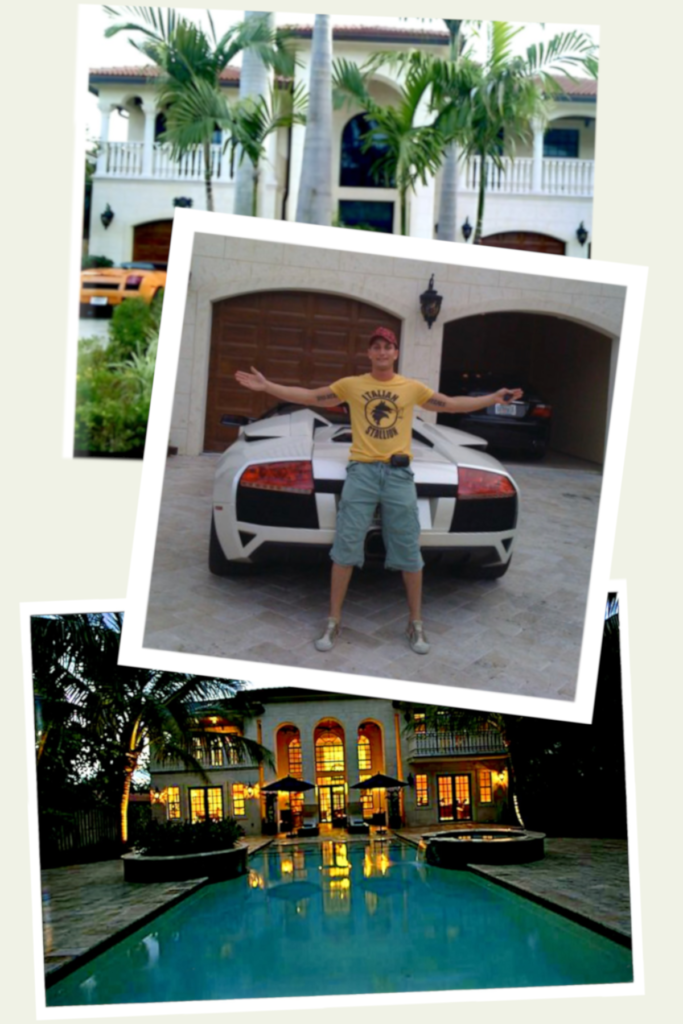

They dug in and quickly rose to the top of the pack. Over the next year, they averaged “unheard of commissions,” according to Vitale, in excess of $100,000 per month. He got his own place and bought a black, heart-pounding five hundred horsepower BMW M6. Life was getting good.

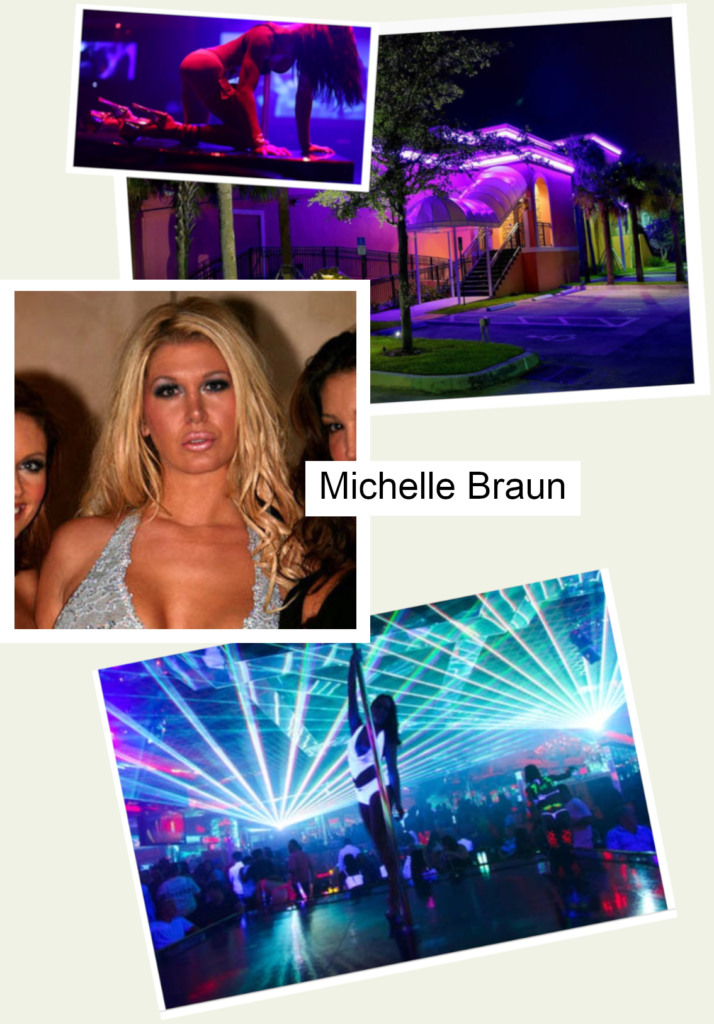

THE BROKERAGE INDUSTRY as a whole, according Vitale, is designed to look professional, conservative, stable, and above all trustworthy. But he quickly learned it’s teeming with questionable characters. “Degenerate gamblers, alcoholics, drug addicts. Functioning addicts like Grossman,” he says, “but they’re still addicts; and I was no exception.” The average broker’s day starts around six a.m.—assuming he ever went to sleep—with several cups of coffee and some cocaine, confesses Vitale. He might analyze some financial reports and put in a few trades. “Around nine you start smashing out calls to doctors, lawyers, business owners, anyone with the ability to invest big money. More coke at lunch—basically, you’re doing coke throughout the day. Everyone’s driving a Mercedes or a Porsche or a Lambo—”

“What about after work?” I interrupt.

“After?” Vitale hesitates. I can see that he’s questioning how much to disclose, and I remind him that he agreed to tell me everything. “Strip clubs and hookers—you don’t have time to do anything else. Drugs, strip clubs, prostitutes, sports cars, and lots of money. That’s why so many of these guys end up in rehabs and divorced, getting DUI’s or killing themselves in car accidents. It’s fuckin’ chaos.”

In fact, despite that his parents had come around once Vitale appeared to be doing well, his lifestyle remained a constant point of contention. He seldom answered his father’s calls or emails and missed numerous family functions. “Look, at the time,” Vitale’s answer trails off as he searches for an acceptable excuse, however, we both know there isn’t one. “I was so busy, and so, yeah, I neglected my family. But that was the lifestyle, not me.”

That was the life of a high-pressure broker.

GROSSMAN STARTED MISSING appointments, “blowing off” work, and not returning calls. By the end of the year he was only coming in one day a week. His absentees got so bad that the firm’s manager started transferring clients to Vitale, who didn’t have any idea of how to trade stocks.

“He’d never taught me that part of the business,” says Vitale. “The truth is, he didn’t want me to know how to trade; he was getting half of everything I brought in.” Grossman would invest the client’s money into a stock and he and Vitale would split the commission. “It didn’t matter if it made money or not.”

Over the next few months Vitale simultaneously brought in new accounts, while teaching himself to trade. Eventually Vitale was running his and Grossman’s accounts—raising money, analyzing stocks, and making the trades.

“What did Grossman say about that?” I ask.

“He wasn’t happy about it,” confesses Vitale. However, Grossman was doing “roxies” (oxycodone) and cocaine to excess, as well as not coming in to work on a regular basis. “The manager got tired of it; there was a big argument and he fired Grossman.”

This time, however, the younger broker refused to abandon ship. He’d come to the conclusion that, despite Grossman’s experience, he was better off without him. He buckled down and hit the phones. Over the next year he raked in hundreds of new accounts as well as massive commissions.

BY MID-2008, the DOW Jones Industrial Average Index was in free-fall. Between Lehman Brothers, Bear Stearns, Merrill Lynch, Goldman Sachs, and Morgan Stanley alone, there were reported losses of over $4.1 trillion. Roughly thirty percent of U.S. GDP for 2007 had vanished and the entire financial system was melting down.

New business slowed considerably. Clients started pulling out of the market and liquidating their assets. Regardless of the financial crises Vitale didn’t feel the pinch nearly as much as his brethren. Specifically, because he moved his clients’ assets into “Ultra Shorts.” In fact, in November 2008, he made J.P. Turner’s “Heavy Hitters List.” Out of the firm’s 20,000 brokers nationwide, Vitale ranked among the top ten.

The banks had stopped extending credit and businesses were desperate for cash. The opportunist in Vitale recognized the potential to capitalize on the lack of liquidity. He resigned from J.P. Turner and began making calls to private equity firms. Vitale ended up taking a position with Balfaur Management which came with a signing bonus—a yellow Lamborghini Gallardo—and a twenty-five percent commission on everything he raised.

The exorbitant commission structure—like most of the private equity industry—was sketchy. Due to the excessive amount of the commissions, firms typically don’t disclose the size of their commissions to their investors, thereby making it illegal. Yet, highly lucrative.

The offices of Balfaur Management were located on the fourteenth floor of the Bank of American Building in Ft. Lauderdale, just below Scott Rothstein’s office; coincidently, during the same time period, Rothstein ran the largest Ponzi scheme in Florida history.∗

Vitale brought in several of his own brokers—heavy hitters like himself—and the team began “cranking out calls.” Within the first two months they’d raised over $2 million for Helix Wind, a company out of California that manufactured computer chips; as well as bringing in several million dollars for multiple other companies.

Vitale was twenty-three and living like a rock star.

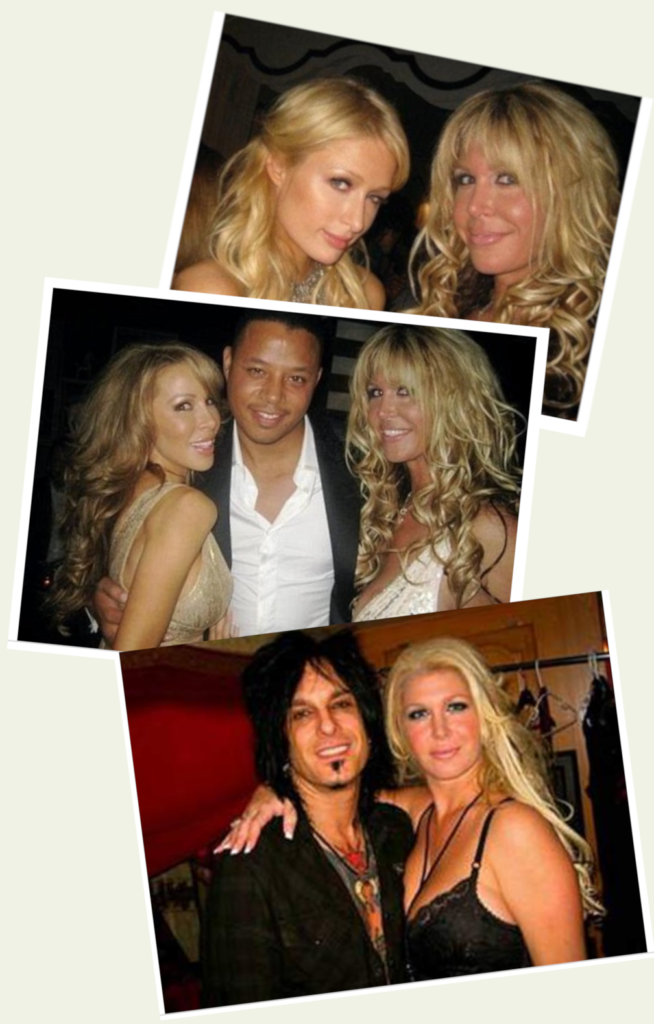

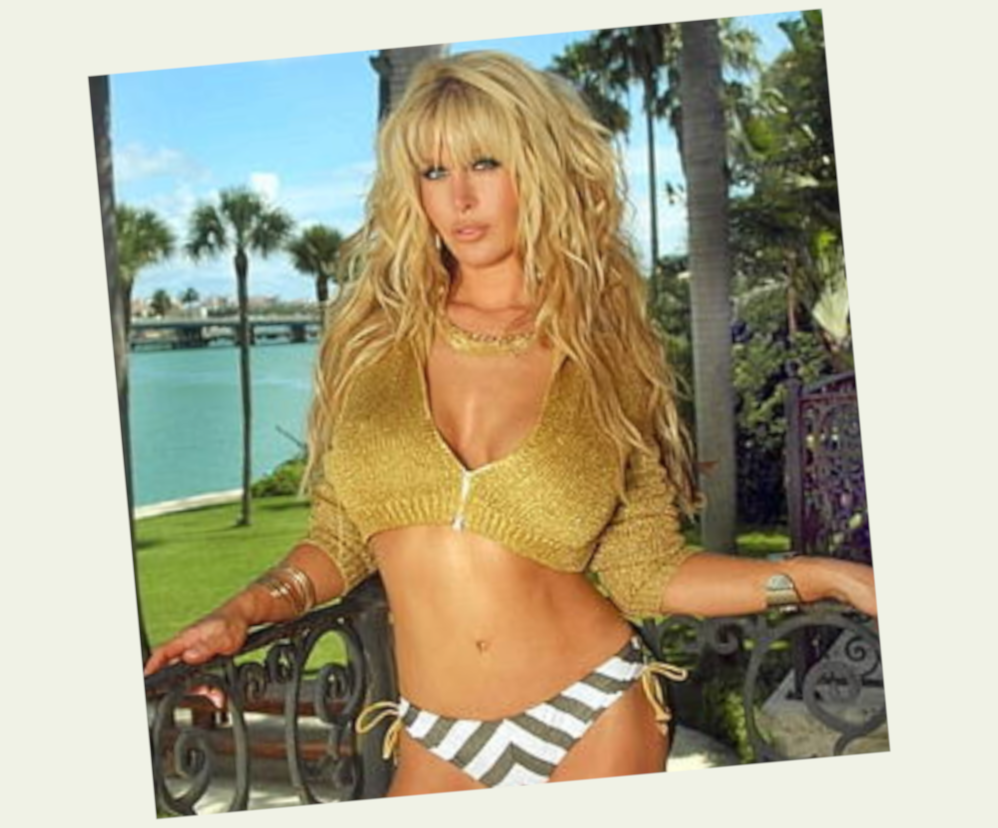

THE LONG LEGGED BLONDE BOMBSHELL that sauntered into the Solid Gold Gentlemen’s Club, in February 2009, was not a stripper, although, she was deep into the sex trade.

Michelle Braun—with her enhanced Angelina Jolie lips and Pamela Anderson breasts—was synthetically attractive in an excessive plastic surgery kind of way. The Barbie Doll beautiful Braun was smart and confident to the point of being cocky; she’d spent more than a decade running the exclusive members only escort services: NicisGirls and BellaModels.

Specifically, Braun had taken the escort business to a new level of profitability by connecting Playboy models and porn stars with wealthy actors and sports stars like Charlie Sheen, Mickey Rourke, Courtney Love, Tiger Woods, and Jose Canseco as well as Russian oligarchs and princes from Dubai to Istanbul.

During Braun’s tenure she’d made nearly $9 million, however, due to an ongoing federal investigation and media interest in her high profile clientele, the high-end cyber madam had recently fallen on hard times. She was desperate, but when Braun stepped into Solid Gold that February, she had a plan.

Braun recognized Vitale by his signature three-piece-suit. He was seated in a private area near the stage along with several of his brokers, surrounded by six gorgeous Solid Gold exotic dancers. The group was half drunk, “lit up” on cocaine, and watching multiple dancers work the stripper-poles on stage when Braun tapped Vitale on the shoulder.

“Is that your Lamborghini outside?” she yelled over the club’s music. Vitale proudly admitted the European super car was, in fact, his. The long legged blonde threw out her hand and introduced herself as an equity financier—an individual who acts as an intermediary between investment bankers and companies in need of financing. In addition, Braun confided she was “John Boyle’s girlfriend; he told me I should talk to you. It’s regarding startup capital for a project I’m shepherding.”

Boyle was a wealthy trust fund scion, heir to his family’s lucrative development company—worth several hundred million dollars—and highly respected. As such, Vitale had no reason to doubt Braun’s credibility.

“Sure, I know John,” he replied, a little shocked that Braun had approached him in a strip club, “but, maybe we should meet at my office tomorrow morning.”

Vitale walked Braun outside and handed her his business card. Admittedly, he was impressed by her confidence and the black Rolls Royce Phantom she drove off in.

The next morning, Braun laid out the opportunity; an alternative energy company, Agro Energy, had a revolutionary refining technique to convert algae into bio diesel fuel. “We need to raise five million,” she confessed. “Can you do five?”

“If it’s sound,” Vitale replied, “yeah, I can do five.”

Braun scheduled a meeting with Agro Energy’s CFO Mark Yagala and Professor Jacob Gittman, PhD. The professor was not only in charge of the science and manufacturing behind the company, he was also the owner.

Days later, Vitale and Braun arrived at the Miami office building. Both Yagala and Gittman were already seated at the table in the conference room when the secretary led Vitale and Braun in.

Introductions were made, the professor handed everyone some promotional material and went into the science behind the refinement process. He gave specifics on how the $5 million would be spent; including the construction of a prototype factory outside of Miami, the custom equipment necessary for the refinement process, and operational expenses.

“It was an impressive presentation,” admits Vitale. “No red flags went up. The professor (Gittman) seemed extremely knowledgeable; Yagala—the CFO—said very little, but he seemed professional . . . I had a good feeling about it.”

Braun called Vitale over the next several days; attempting to pressure him into committing to the project. He had his attorney conduct a background check on Professor Gittman—Agro Energy’s owner—but never considered looking into its CFO or the pushy equity financier.

Less than a week later, Vitale’s lawyer informed him that Gittman as well as the company were solid.

Vitale was in the midst of several projects, however, he told Braun that he’d agree to raise the capital for a twenty-five percent commission. “Once we reach five,” he explained, “we’ll do another raise to bridge any gaps in capital.”

The next morning she showed up at his office with all of the paperwork—Private Placement Memorandum, Subscription Agreement, everything he’d requested.

“All you’ve gotta do is sign,” said Braun and she thrust a pen at him.

Braun insisted they open a corporation, Sterling Capital Trust LLC, to collect the investor funds, which, as the LLC’s vice president, she would release to Agro Energy as they assigned the investors stock certificates. It made sense to the seasoned broker. In fact, Vitale personally accompanied Braun to TD Bank to open the corporate account.

“AGRO ENERGY—I HAVE NO DOUBT—will be the next Exxon Mobil,” said Yagala, the company’s CFO, during a gathering of Vitale’s brokers at his office in the Bank of America building on April 6, 2009. He handed out promotional material and answered questions. According to Vitale, Yagala delivered one of the most informative and concise presentations he’d ever heard in connection with a startup’s growth potential.

The brokers were so energized by the explosive numbers they started “smashing” the phones, “cold calling” potential investors up to ten hours a day for a month straight; and the money began coming in.

Sterling Capital had raised over $450,000 of Agro Energy’s required $5 million when the team manager, Brian Dunlevy, informed Vitale “there’s an investor on line six for you.”

It seemed like a benign call from an investor; he’d put $30,000 into Agro Energy. “It’s been over thirty days and I still haven’t received my stock certificates. I should’ve gotten them by now.”

“Yes sir,” agreed Vitale, “you should have.” He promised to look into the delay and get back with him.

Vitale didn’t know it yet, but that call was the first rumble of what would become an avalanche that would irrevocably derail the remainder of Vitale’s life.

Over the next two days Vitale sent Braun several emails enquiring when she planned to issue the certificates; with no response. As more investors requested the documents, Vitale began frantically firing off emails and leaving voice messages. But Braun couldn’t be reached.

Finally, after realizing she’d changed the online password—thereby locking Vitale out—to Sterling Capital’s account, he drove to TD Bank and spoke with the manager. She pulled up the account’s most recent transactions. Out of the $450,000 raised, Braun had drained $370,000—Puppy Palace got $2,000, $20,000 went to the local Mercedes dealer, $7,500 for her rent, Club Liv got $15,000, and the remainder was spent on a massive designer shopping spree—leaving a balance $80,000.

At the sight of it Vitale’s stomach tightened into a knot, and the room spun around him as desperation set in. In a panic he punched in the number of Agro Energy’s CFO. “Mr. Yagala, this is Joe Vitale, she spent the money,” he sputtered. “Michelle Braun—your equity financier spent it—”

“What money?” replied Yagala. According to the CFO, Braun had told him that Vitale’s team hadn’t started the raise.

Vitale frantically described the situation; his main concern being, “I owe my clients four hundred and fifty-thousand dollars of Agro Energy stock.” Standing in the bank’s parking lot, staring at his Lamborghini his mind drifted to his old Volkswagen Passat, and he said, “I’ve gotta call the FBI—”

“Wait a minute now, let’s not involve the authorities just yet.” Yagala was concerned that the energy company’s name might be damaged by an investigation; making it impossible to raise the $5 million they still needed.

He suggested that Vitale wire him the remaining $80,000 and he would issue the $450,000 in stock out of his personal shares. “But you have to keep this between us; the professor would never approve.”

“Of course,” he said. “Of course.”

Vitale immediately stepped into the bank and instructed the manager to wire Yagala the account’s remaining balance. Everything’s gonna workout, he told himself. Unfortunately, when Vitale called the company’s CFO the next morning to arrange for the stock to be assigned, Yagala failed to return any of his messages.

By the end of the workday Vitale had come to the conclusion that Yagala, Braun, and the money . . . were gone. He’d been conned.

“WAIT A SECOND,” I interrupt. “That’s all they got, four hundred and fifty grand?” Vitale and I are seated in an area within the low security prison’s recreation center. In the distance—past the fences and razor-wire—the sun is sinking behind one of the Coleman complex’s two penitentiaries.

“Yeah,” he confesses. “She and Yagala got four-fifty.”

“You got lucky.” I point out that had Braun simply fabricated the Agro Energy stock certificates and issued them to the investors “they wouldn’t have known the difference; and you wouldn’t have gotten tipped off . . . You would’ve raised the whole five million.”

“Absolutely,” says Vitale. He estimated that within six to ten months he and his team would have raised the capital.

“See, that bothers me,” I admit. As a con man I’m personally offended that Braun didn’t perform the basic maintenance required to maximize the take. “She left over four and a half million on the table; it’s just sloppy. Unprofessional. She could’ve gotten you for the whole five.” Vitale stares blankly. Dumbfounded. His brow half arched and his lips slightly adjure. Unmoved, I continue, “I’m just sayin’ . . . I’d have gotten you for the whole five.”

SITTING IN HIS ATTORNEY’S office, in June 2009, Vitale described how thoroughly Braun had duped him. He’d already repaid $250,000—out of his own pocket—to the investors that he had contact information on. However, the remaining clients contact information was in Braun’s laptop, but she’d disappeared.

“Calling the authorities is out,” said the lawyer. Vitale had opened the company—he was listed as the CEO—opened the corporate account, raised all of the capital, and then personally wired the last of his funds to Yagala—one of the conspirators. “They’re absolutely going to conclude that you’re involved.”

“So what do I do?”

“You need to get that laptop.”

On Vitale’s way out he called Braun’s cell and left her a message pleading with her to email him the clients’ contact info as well as the amount each had invested. “I’ll pay ’em back,” he explained, “you can keep the money.” Still, she didn’t respond. No email, text, or voice message. Just radio silence. Desperate to find a solution, Vitale called Professor Gittman at the office. He told him he was trying to reach Yagala.

“Who?” he replied.

“Yagala, your chief financial officer.” Vitale reminded him that Yagala had been at the professor’s presentation months earlier. “Mark Yagala, he’s the company’s CFO.”

“I don’t have a CFO,” Gittman stated, emphatically. “That guy was with you and Ms. Braun.” In fact, the professor informed Vitale that Yagala had arrived shortly before he and Braun. He further revealed that Braun had told him that Vitale had “passed on the opportunity” to raise the $5 million in capital.

“No, no, that’s not true,” stammered Vitale. “We’re in the middle of the raise right now, but Michelle [Braun] and Yagala stole the money.”

He rambled off the events of the past two weeks—including his desperate attempt to locate Braun or Yagala so he could repay the investors. Unfortunately, the professor wasn’t in a position to help. “I’m sorry Mr. Vitale, it sounds like you’ve been the victim of an elaborate confidence game.”

Unbeknownst to Vitale, Gittman was so unnerved by what he’d heard, within minutes of finishing the call, he notified Broward County’s Sheriff’s Office of the incident. This sparked an investigation into Sterling Capital Trust LLC, its Chief Executive Officer Joseph Vitale and Michelle Braun, the company’s Vice President.

OVER COLD TATER TOTS and burnt veggie-burgers in the prison’s cafeteria, Vitale explains that—due to Braun’s refusal to provide him with the investors’ info—he was unable to repay all of the stolen funds. “Every few months I’d get a call asking if we’d done the raise for Agro,” says Vitale. “I’d explain that there’d been an issue, I’d apologize, and wire them their money back. But they weren’t all able to track me down.” With no clear solution, all he could do was hope that, “eventually, all off Agro Energy’s investors would reach out to me.”

“You were in a bad spot,” I offer.

“It was like a black cloud over me,” replies Vitale. “Eventually though, I put it behind me and, and I just, you know . . . I just kept doin’ what I do.”

VITALE’S NEW PEARL WHITE LAMBORGHINI Mercialago was parked in the garage—wedged between his white Mercedes and black Lexus—of his $2.8 million beachfront home. All 10,000 square feet of the opulent Mediterranean had been decorated for Vitale’s New Years Eve black-tie blowout.

There were live mermaids in the pool, fire dancers walking the premises, top-shelf caterers serving, and two fully stocked open bars. Naked escorts were available in the upstairs bedrooms and cocaine in the master suite. “It was,” according to Vitale, “complete decadence and debauchery. I dropped forty-thousand on the entertainment, alone—not including the hookers.”

Five hundred guests—south Florida socialites, businessmen, and investors—stood shoulder-to-shoulder to bring in 2010. While he watched the ball drop on his monster-flat-screen, Vitale thought, with the exception of the Michelle Braun thing, I’ve had a pretty fuckin’ amazing year. He’d raised $10 million in capital for a technology company out of north Florida and was in the middle of raising $7 million for an Internet streaming startup. I love my life, he told himself, and it’s only gonna get better.

THE U.S. MARSHALS kicked in the front door at eight a.m., in early 2011. They had a warrant for Vitale’s arrest— he’d been charged by the State of Florida with unlawful operation of a boiler-room. Regardless, the marshals had missed him. Coincidently, Vitale had stayed the night at a girlfriend’s place, as a result, he wasn’t home during the raid.

After his criminal attorney had arranged for bond, a month later, Vitale turned himself in to Broward County Sheriff’s Department. He was booked, photographed, finger printed, and released within hours.

Over the course of a couple years he and his co-defendants lawyers negotiated a variety of plea bargains. Vitale agreed to serve one year of home confinement, four years probation, and pay—$105,000—the outstanding balance owed to the victims.

Despite the fact that Braun was the ringleader of the stock scam—in addition to having recently plead guilty to charges of transporting an individual for the purpose of prostitution and money laundering in federal court—amazingly she was granted the same deal as Vitale.

The bulk of Vitale and Braun’s six additional co-defendants received similar sentences.

Brian Dunlevy—the team manager—however, refused to accept a deal, instead opting to throw himself on the mercy of the court. He received fifteen years. According to Vitale, Dunlevy had done nothing more than fall for Braun’s scam.

Miraculously, Yagala—who was already on federal probation for a fraud charge—somehow managed to avoid being indicted altogether.

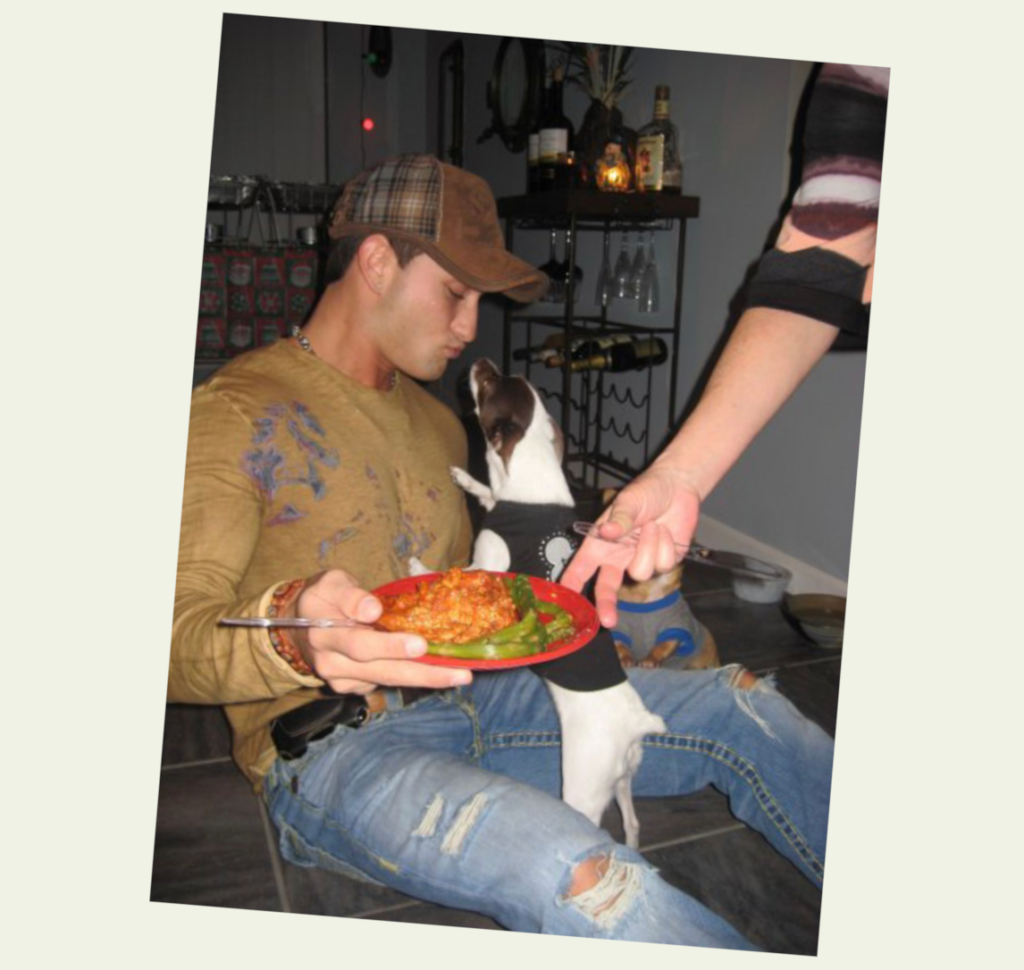

FRESH OFF OF HOUSE ARREST Vitale and his girl, Mariuxi Carrera—a hard-bodied Ecuadorian beauty in her thirties he’d recently gotten serious with—were sprawled out in lounge chairs at Ft. Lauderdale Beach. Her three-year old son sat nearby playing. Tourists and locals were enjoying a children’s festival with clowns making balloon animals, cotton candy, and icys several hundred yards away. Close to twenty bouncy-houses and water-slides littered the dunes.

It was Memorial Day, 2015, and Vitale was watching Mariuxi’s son build a sand castle when he noticed a large tornado coming in from the ocean. That’s odd, he thought, as the storm system reached land near the festival. Vitale had never seen anything like it, nor did he understand the strength of the weather anomaly.

Before he realized the danger, parents and children began to scream as the lightweight bouncy-houses and slides started to teeter and shift in the wind. Suddenly, one of the bouncy-houses—packed with over a dozen kids—was lifted off the ground by the tornado and launched ninety feet into the storms spiral.

The structure traveled through the air, over the beach, and dropped into the traffic on Ocean Drive—multiple kids received injuries ranging from scratches to broken bones, however, all of the children survived.

“That’s where I saw Royce [Teets], at a restaurant on the beach,” Vitale informs me. “Right after the bouncy house thing.” They’d worked together several years earlier on a raise, but hadn’t spoken since. “Royce told me he had a nice office downtown and ten brokers working for ‘im.” The firm specialized in raises for exempt private offerings, as a result, none of the brokers needed their series-seven. Royce said was he was “kicking ass,” still, he needed a “super star” like Vitale to take it to the next level. He suggested they become partners, “but I declined.”

Vitale was on state probation and reluctant to get involved. Royce understood his dilemma, and he suggested that he simply use an alias. Vitale was still apprehensive, however, he hadn’t worked in over a year and his savings were dwindling. He agreed to stop by and checkout the operation. “Royce’s guys were working the phones, pitching prospective investors. It got my adrenalin pumping and I immediately knew I wanted in,” says Vitale. “Outta the gate—my first month—I opened forty new accounts. Made fifty grand like it was nothin’. I hadn’t realized how much I missed it, and then, you know . . . it was on.”

Understand, the governors restraining Vitale—such as the threat of losing his license and damaging his reputation—vanished the moment he became a felon and actually lost his licenses. Additionally, using the alias Donovan Kelly and working on non-registered raises only amplified his reckless behavior. Vitale admits, “I’d say anything, short of promising clients a guaranteed return, to open an account.”

Once the money started coming in Vitale began teaching the other brokers how to pitch deals using a variety of closing techniques. “The economic close, the takeaway close, the soft close, the hard close . . . After awhile the place was a fuckin’ powerhouse—a real live boiler-room—raising tens of millions.”

“NINE OUT OF TEN STARTUPS FAIL,” admitted Vitale. “Those are the stats.” It was the day before Thanksgiving and the hard-core brokers were working the phones. Smashing potential investors. Vitale let the statement sink in and he closed with, “but in my professional opinion, this is the startup that makes it. This is the next Apple, the next FedEx, the next Facebook, the next Twitter; this is the investment that makes you a millionaire . . . or not. There’s nothing wrong with being middle-class; guys like you are the backbone of this country.”

The potential client emptied out his IRA and invested $33,000. Vitale has no idea what became of the startup. However, he did recall that his father called the next morning to remind him that he’d promised to be at his house by four p.m. for Thanksgiving dinner.

“Of course I’ll be there,” Vitale assured him; lying in bed hung over and groggy. “Four, no problem.”

“You’re sure?” his father asked. “We’re all here.”

“Of course.”

Unfortunately, by the time Vitale was on the Interstate he’d done a few lines of cocaine and was in no mood for dinner with the family. Then, he saw a billboard for the Hard Rock Casino. No, he thought, they can’t be open on Thanksgiving. Sure enough, when he pulled his Lamborghini up to the valet the guy said they were open. Vitale spent that night losing $25,000 on blackjack while directing his father’s calls to voicemail.

“ME AND ROYCE were never really cool,” says Vitale. “He was always talkin’ shit about people—that guy’s a fucking idiot or she’s a whore. It got old real quick.”

The other issue Vitale had with Royce was his propensity to act like he was some type of mobster. He’d make comments about loyalty or how he’d “like to stick a fuckin’ bomb in some disloyal broker’s Porsche or pop a hole in a competing venture capitalist’s head. That just wasn’t cool. I’m not a gangster and I didn’t wanna hang out with someone who thought he was.”

Once, Vitale tells me, he and Royce were drinking at the office and his partner explained Florida’s Castle law, which states that if someone is on his or her property and they feel threatened by an individual, the property owner has the right—by law—to use deadly force.

“Nah,” replied Vitale. “That can’t be right; you can’t just kill someone.”

“Bro, they’ve got the Castle law and the Stand Your Ground law,” said Royce. “This isn’t New York or California; this is the south. These hillbillies shoot each other all the time. It’s not that hard to get away with murder down here.”

It wasn’t the defining factor as to why Vitale disliked Royce; however, the conversation is worth noting.

WORKING THAT POLE can’t be easy, thought Vitale, unabashedly staring at the stripper on stage at Scarlet’s Gentlemen’s Club. He and Mariuxi watched from the VIP section as the dancer straddled the cylindrical chrome then slowly spun around the prop, gently coming to her feet. She gave Vitale a girlish-wave as she sashayed down the catwalk. The instant she disappeared behind the curtain three more stripper sauntered out.

Vinessa Noriega and a few of her friends were seated near Vitale and his girl inside the exclusive area of the club. Vinessa was an attractive thirty-year-old brunette-Latina; a younger more “street” version of Jennifer Lopez. Her diamond-studded-grill, tight designer outfit, and brash ghetto attitude let everyone know she had some money, but she was also a little dangerous.

Despite the description, according to Vitale, there was something sexy about “V.”

Throughout the night the groups merged, and Vitale ended up doing several line of cocaine with Vinessa in the restroom. She slipped him her number and indicated she always had “weed and blow.”

From then on, Vinessa was always around; she’d stop by the office, flirt with the guys, give “blow jobs” in the back room, and “hookup” with everyone at various strip clubs after work. Before long, Vinessa was supplying half of the brokers with whatever drugs they wanted.

“LOTTONET,” ANNOUNCED ROYCE. “It’s a tech company.” He and Vitale were standing in Royce’s private office far from the shouting and turmoil of the brokers in the bull-pen. Staring out of the window at the federal building—which housed the FBI and the federal courthouse among other government agencies—Vitale realized Royce was hung-over. “I need you to close this guy. It’s a great opportunity.”

Twenty minutes later the owner of LottoNet, David Gray, stopped by the office. Gray was a computer geek cut with some frat boy cocky. He described the company as a concierge service that gave costumers the ability to play all of the state lotteries using their web-app. It was a compelling presentation and the statistics were astonishing. So much so, that Vitale made it a point to jot them down.

Gray had a solid concept and he knew it. “What I want to know,” asked the startup’s owner, his eyes pinging between Royce and Vitale, “can you guys raise the five million or not?”

Vitale scrunched his upper lip into a snicker. Earlier in the day he’d spoken with a potential investor he’d yet to pitch a private placement. He dialed the lead’s number and placed him on speakerphone. “Dan,” he pounced before the investor could answer. “I don’t have a lot a’ time; an opportunity just hit my desk, LottoNet, tech company with massive revenue potential.” Vitale glanced at the figures he’d scribbled minutes earlier and rambled off the number in an adrenalin-infused, polished, non-stop pitch. “Two hundred and ninety-two million is spent on U.S. based-lotteries per day. Now—hypothetically—if LottoNet were to capture a one percent share, that’d come to thirty-million a day in gross revenues, which—on a fifty-thousand dollar investment—would equal fifty-three thousand per month. Again, persuaded-hypothetically.” Vitale never even gave the investor an opportunity to comment before he hit him with “look, Dan, I’ve got forty other investors to call today—are you in or out?”

“I’m in,” he enthusiastically replied, “I’m in, send me the wiring instructions.”

Vitale transferred the call to the office manager, turned to Gray, and asked, “My question to you is, are you ready to do this?”

Royce agreed to a fifty-fifty partnership on the LottoNet raise after Vitale persuaded Gray to entertain a double equity raise consisting of an initial raise of $5 million followed by a second raise of $5 million—totaling $10 million at a forty percent commission.

It took two months for the LottoNet app to go up, but once it did, the floodgates opened. Within months, Vitale and the brokers had raked in $3 million. Royce, however, had only raised $12,500 of it.

“That was in December 2015,” recalls Vitale; Royce had taken his girlfriend, Terri Coolidge, to Italy where he’d bought her a 4.9 carat engagement ring, “which was great—’cause I loved Terri—but he started doing more and more drugs—coke, oxies, adderol . . . alcohol. After that, he stopped coming in. He became useless.”

“WHERE’S MY NIGGER?!” yelled the chunky white seventy-year-old, Vitale knew as Old Man Bruce. “Get me my nigger!” One of his four private security personnel immediately moved to find the strip club manager. A second security guard exited the club to get the supplies.

Vitale had been dragged to the VIP area by one of the Solid Gold dancers an hour earlier. Old Man Bruce wanted some cocaine and all of the girls knew that Vitale typically had some on him. Subsequently, he’d joined the party made-up of four body guards, nearly a dozen exotic dances, a couple of the old man’s associates, and an aging multi-millionaire—one of the majority shareholders in Home Depot worth nearly half a billion dollars—that was insistent on getting his hands on an African American dancer.

Vitale turned to the stripper next to him—she was snorting a line of cocaine off of the table—and he asked, “What’s going on?”

She wiped her nose, did a hair flip and giggled. “Yeah, so like . . . Bruce’s gotta thing he does with the black girls—he likes to paint ’em white and do ’em doggy in the back room.”

“Seriously?” gasped Vitale. “How often does he do this?”

Suddenly, the manager appeared with a gorgeous African-American dancer, accompanied by one of Bruce’s bodyguards holding a five gallon paint bucket and some painting equipment. He pulled off the lid, placed a screen inside the container, and handed a paint-roller to Bruce.

Vitale’s companion leaned into him and whispered, “Here he goes.”

The black dancer slipped off her bikini and stepped in front of the seventy-year-old seated in his chair. She stared down at him as he worked the roller over her naked body. The old man slopped white paint all over the stripper as well as the carpet, himself, and the chair.

It all happened so fast, Vitale was still reeling from the use of the “n-word” and Bruce’s poor painting skills when his cell rang. It was his father, but he wasn’t about to take the call. Vitale was too coked-up and too appalled by what he was witnessing to deal with his father. Vitale noticed that she was coming out more like a zebra than a white girl. But she didn’t seem offended, in fact, she couldn’t stop grinning and laughing.

Even stranger than the spectacle, was that no one else seemed shocked. Not the security guards, the manager or the other dancers—they’d seen it all before. I cannot fucking believe this is my life, thought Vitale. This is insanity.

VITALE’S NEW BOILER-ROOM was straight out of the Wolf of Wall Street, a massive 5,000 square foot office space and an additional 3,500 feet, housing LottoNet’s’ tech support and new headquarters. All of it equipped with modern office furniture and state-of-the-art computers.

The soul of the operation, however, were the twenty guys—fronters, new account openers, and loaders—in the bull-pen. Each and every one of them cranking out call after call to potential clients using a variety of high-pressure tactics. Rattling off scripted pitches into headsets hour after hour after hour.

Vinessa, of course, was always in and out of the place. Dropping off cocaine, marijuana or whatever the brokers needed to keep them pushing LottoNet stock.

The best part of the new office, according to Vitale, wasn’t the pool table or full-bar, it was the stage he’d had installed—complete with a stripper-pole.

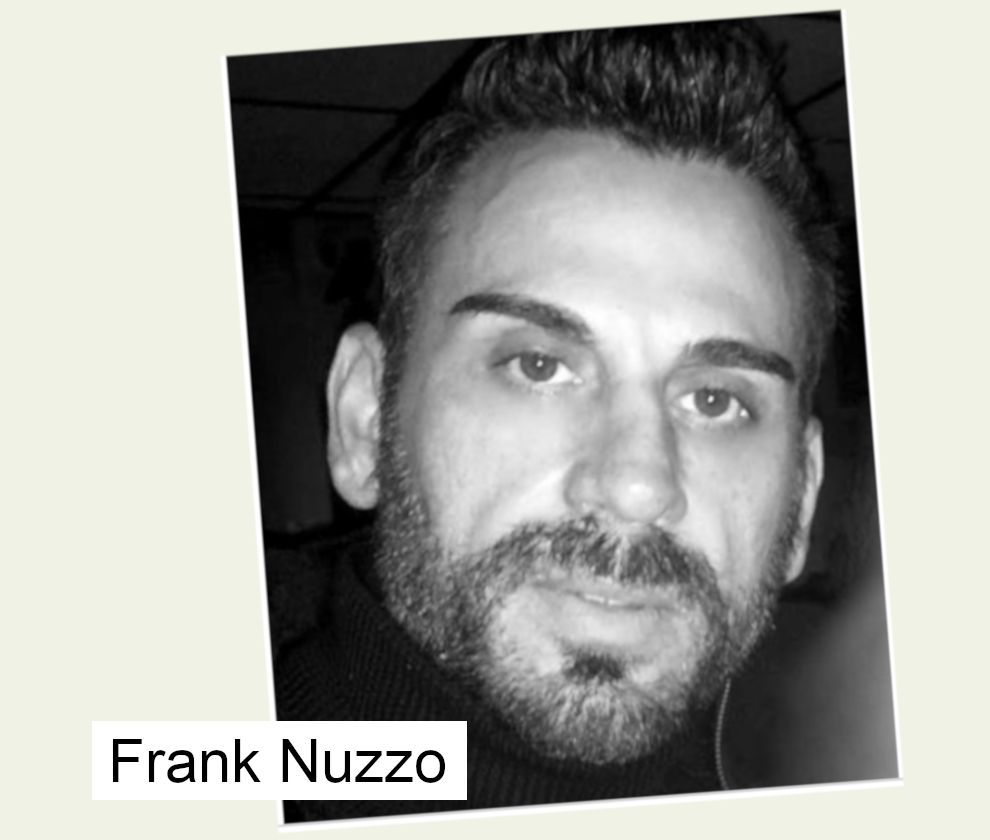

ANTHONY CALAVOPE looked vaguely familiar as he approached Vitale’s one hundred thousand dollar custom made Jeep Wrangler at Hollywood International Airport’s express lane.

Vitale had met Calavope months earlier through a potential client—Thomas Jacobson out of Texas—whom he’d pitched LottoNet. The Texan liked what he’d heard, however, he wanted Vitale to run it by his financial advisor.

Calavope was out of Las Vegas and—despite being in competing industries—after a three hour phone call, wherein they battled over public versus private stocks, IPO’s, and the viability of emerging markets, Vitale sold him on LottoNet. In fact, Calavope was so taken with the opportunity, not only did he advise Jacobson to invest, he agreed to pitch the startup to his entire client pool.

Over the next two months Vitale and Calavope pitched twenty of his clients, raising $1.5 million while building a strong long-distance friendship. But, they’d never met in person.

After the million and a half, however, Vitale invited Calavope to come see his operation. He wanted him to be a part of the team. Still, he definitely recognized Calavope from somewhere. So, before getting out of the Jeep Vitale whipped out his smartphone and surreptitiously snapped a photo of him.

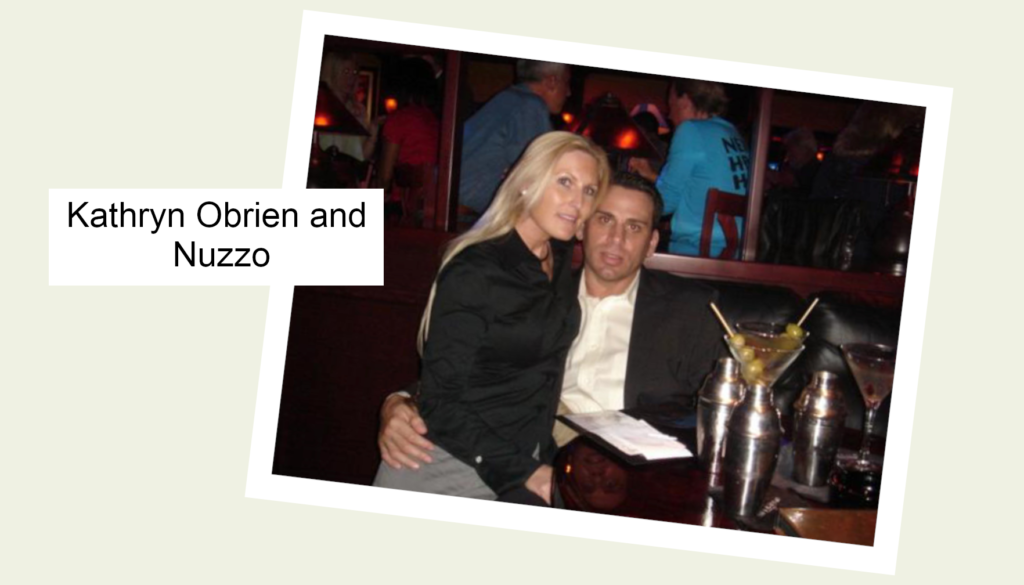

That night—after dropping Calavope and his fiancée, Kathryn Obrien, off—Vitale stopped by Royce’s place. It was seven p.m. and he was already drunk. Regardless, Vitale showed him the photo and questioned if he recognized Calavope.

According to Vitale, Royce turned white and slurred, “This a joke? That’s my mentor, Frank Nuzzo; I showed you his mug shot.” Vitale recalled that Royce had pulled up Nuzzo’s booking photo domestic violence while describing their failed business relationship. “He ripped me off. The guy’s a scumbag.”

Based on his experience, Vitale doubted Royce’s word. Nuzzo—other than the use of an alias—had never lied to him, in addition to being a workhorse that had just raised $1.5 million for LottoNet. Royce, however, hadn’t lived up to one of the multitude of promises he’d made to Vitale. “We need this guy,” he stated. “He’s a fuckin’ machine.”

“No,” Royce grunted, defiantly, “he’s evil. I don’t want ‘im around.”

“Evil? What the fuck are you talkin’ about; I’m not asking your permission,” replied Vitale. He then brought up the fact that Royce didn’t even come into the office anymore. “You’re not pulling your weight and this guy, Nuzzo, is. He’s a closer and he’s staying.”

Two days later Nuzzo and Vitale were in a meeting with Gray discussing the second raise. Nuzzo was pushing for an alternative script when Royce stumbled into the conference room, drunk. He began griping that Nuzzo had fucked him over.

“I carried you Royce,” he replied. “You couldn’t close a door, let alone, a deal without me. You’re a bureaucrat.”

“Fuck you!” shouted Royce. “No, fuck, fuck . . .” Royce lost track of his thought and snarled, “Yeah, fuck you.” Then he staggered out of the room and exited the building.

Vitale called Royce later that night and informed him he was no longer welcome at the office. Royce was making a ton of money for doing absolutely nothing. Vitale instructed him to stay home and stay out of the way.

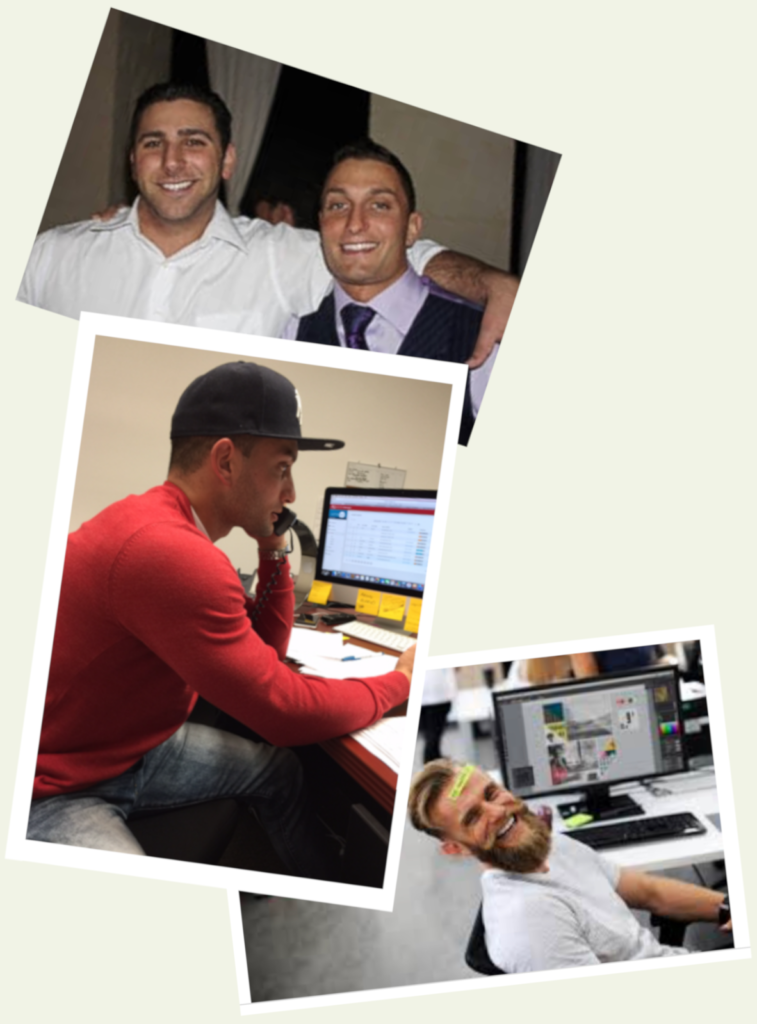

PROFESSIONAL COURTESY, is how Vitale described it. “You know, both Nuzzo and I were using aliases,” he tells me while we wait for one of our classes to start. Although, Vitale was aware of Nuzzo’s real name and Nuzzo was aware of Vitale’s, neither of the con men ever let on that they were aware of the other’s true identity.

“He’s calling me Donovan [Kelly] and I’m calling him Anthony [Calavope], and it’s like we both know.” Vitale laughs at the absurdity of the situation and continues, “But because we’re professionals . . . we say nothing.”

Vitale reflects on the situation and adds, “I loved that guy.”

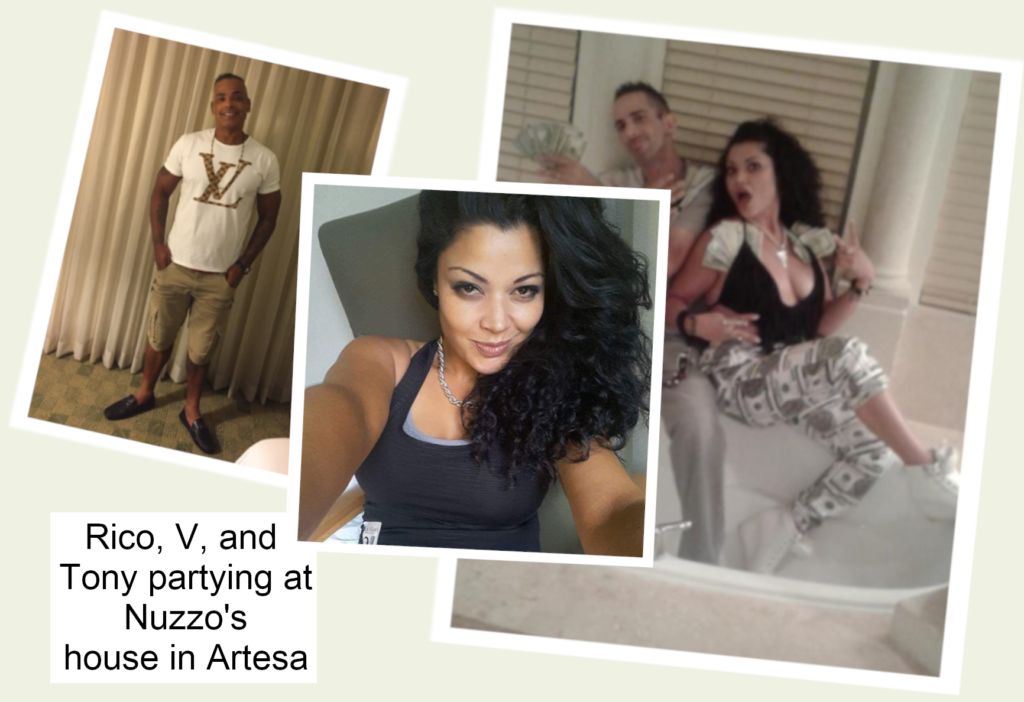

VINESSA AND SEVERAL of the brokers were already at Diamond Dolls strip club when Vitale and Nuzzo arrived. It was after eight p.m. on the first Friday in August 2016, and they were celebrating. Vitale and Nuzzo had raised over a million dollars in less than two weeks.

In the midst of ogling the exotic dancers on stage Vinessa inquired whether Vitale or his “handsome friend” needed anything.

Vitale introduced her to Nuzzo, and, before long they were thick as thieves. They began spending time together. Partying. Whether they were sleeping together Vitale couldn’t tell me, however, he was certain she was supplying Nuzzo with cocaine, weed, and pharmaceuticals.

Although the amount of drugs my have been excessive, Vitale recalls, Nuzzo’s habit was never an issue. He was one of the hardest working brokers Vitale had met.

“HE SEEMED SERIOUS,” warned James Cohen. Royce’s drinking and cocaine use had caused him to cycle between alcohol induced delusions and coke fueled paranoia.

It started with his unfounded belief that Vitale was going to “screw him out of his share” of the LottoNet commission—despite the fact that not one week had gone by that Vitale hadn’t wired Royce his fifty percent.

Both Royce’s fiancée, Terri, and Vitale had tried to convince him to check into a rehab, but he wouldn’t go.

Eventually, his drug paranoia turned to anger, and Royce started making vague comments to Terri, regarding physically harming both Vitale and Nuzzo.

Then, over dinner with a mutual friend, James Cohen, Royce confessed that he believed Vitale was stealing from him and he was planning on killing him. Cohen immediately called Vitale. “I’m telling you he’s talkin’ about having you killed or doing it himself.”

“Nah,” replied Vitale. He insisted that Royce was all talk. “Do you have any idea how much money I’m making ‘im? He’d have to be an idiot to do anything stupid.”

“Okay, I mean, he was pretty fucked up. He’s definitely not thinkin’ clearly.”

Around midnight, two weeks later, Vitale was about to exit the office when he noticed a lone vehicle near his new Ferrari California—there were three, possibly four, males inside. The parking lot was empty—with the exception of the two automobiles—as were the neighboring businesses. It struck Vitale as odd. He thought about Royce’s threat and his gut told him to be concerned. He stood inside peering at the guys in the car outside. The more time that passed the more certain he was that they were waiting for him to exit the building.

Just after two a.m. they drove off.

The next morning Royce notified Vitale’s probation officer that he was using cocaine. She called him in for a “random” urine test, which, miraculously came back negative.

“I CALLED ROYCE and explained that if we couldn’t come to some type of resolution,” says Vitale, “I was going to stop sending him his half of the commissions. He could go open his own place; I was taking over the boiler-room.”

That sent Royce into a full-blown frenzy, wherein he threatened to call the FBI and report the “illegal kickbacks.” But Vitale knew he was bluffing, since that would have opened Royce up to prosecution as well.

Finally, Royce seemed to succumb to reason. He suggested that Vitale stop by his house so they could discuss the issue. Work something out. “I thought, maybe, just maybe we could come up with a settlement and I could pay ‘im off.” Vitale confessed to me during one of our interviews, “I was so thrilled at the idea of getting Royce outta my life that, when he said, ‘call me when you get to the subdivision,’ I didn’t think it was strange.”

WHY ROYCE AND HIS FIANCEE, Terri Coolidge, were arguing prior to Vitale’s arrival, will never be known—Royce has given numerous conflicting versions. However, based on the sequence of events it’s reasonable to infer that Royce intended to kill Vitale, a plan that Terri would have vehemently opposed.

What I am sure of is this, on July 10, 2016, at approximately ten p.m., Royce fired his AK-47 assault rifle, sending a round into Terri’s chest—killing her immediately. Her body dropped to the living room floor. As Terri lied motionless on the hardwood in an ever increasing pool of blood Royce’s cell rang. Vitale was minutes away.

“Do me a favor,” Royce said into the receiver. “Meet me in the back, at the dock.” But Vitale wanted to come in and say hello to Terri. He had pictures of his Fourth of July shenanigans that she just had to see. “She’s sleeping,” Royce retorted, staring down at his former-fiancée. “Don’t come to the front door. Walk around back to the dock.”

The request struck Vitale as odd in connection with Royce’s recent threats. “I don’t know Royce,” replied Vitale wearily; turning his Ferrari into the subdivision, “something’s not right.”

“Bro!” spat Royce. “Just meet me around back.” Vitale could hear the desperation in his disgruntled partner’s voice as he swore, “I’d never hurt you. Terri loves you, you’re like family.”

Whoa, what the hell, thought Vitale. Who said anything about hurting me?

“Alright, Royce, I’ll be there in a minute,” he said. But something was definitely wrong. Vitale called his girl friend, mentioned Royce’s request, and asked, “Does that sound weird to you?”

“Are you crazy?!” she snapped. “Get outta there; this guy’s telling people he’s gonna murder you.”

Vitale agreed, it was a bad idea. He called Royce back and offered to meet him at a steakhouse up the street. Royce, however, got upset and insisted they had to meet at the house. He was adamant there was nothing to worry about. Everything would be okay if he’d just meet him at the dock. But Vitale knew better. He hung up, turned his car around, and headed home.

That was the last time they spoke.

The following morning he received a call from a mutual friend, Angel. He informed Vitale that Royce had shot and killed Terri the night before. “I’m at the house right now,” said Angel. “There are cops and crime-tape everywhere. She’s dead, man. I’m sorry, I know you liked her, but she’s gone.”

“TERRI WAS A GOOD GIRL,” Vitale tells me. A pained expression takes a hold of him and he informs me that she deserved better. “She saw the best in people. She thought she could fix Royce and he killed her for it.”

During the conversation with Angel, Vitale realized that Royce was going to murder him that night. There’s no doubt in his mind. Although Vitale had gotten lucky, he knew it wasn’t over. Understand, Royce was in a considerable amount of trouble, and, knowing Royce, Vitale was certain he would try to talk his way out of it.

“I knew he’d cooperate,” says Vitale, “using the illegal commission as a way to lower his sentence.” Vitale contacted his lawyer who assured him that, at worst, it was a violation of SEC guidelines governing private offerings. “He told me that these things were typically settled civilly. They hardly ever go criminal. So, I wasn’t all that worried about it.”

Shortly thereafter, Royce convinced a federal prosecutor that Vitale, Gray, and Nuzzo were conducting a massive scheme to defraud investors. That, conversation sparked an FBI investigation into LottoNet.

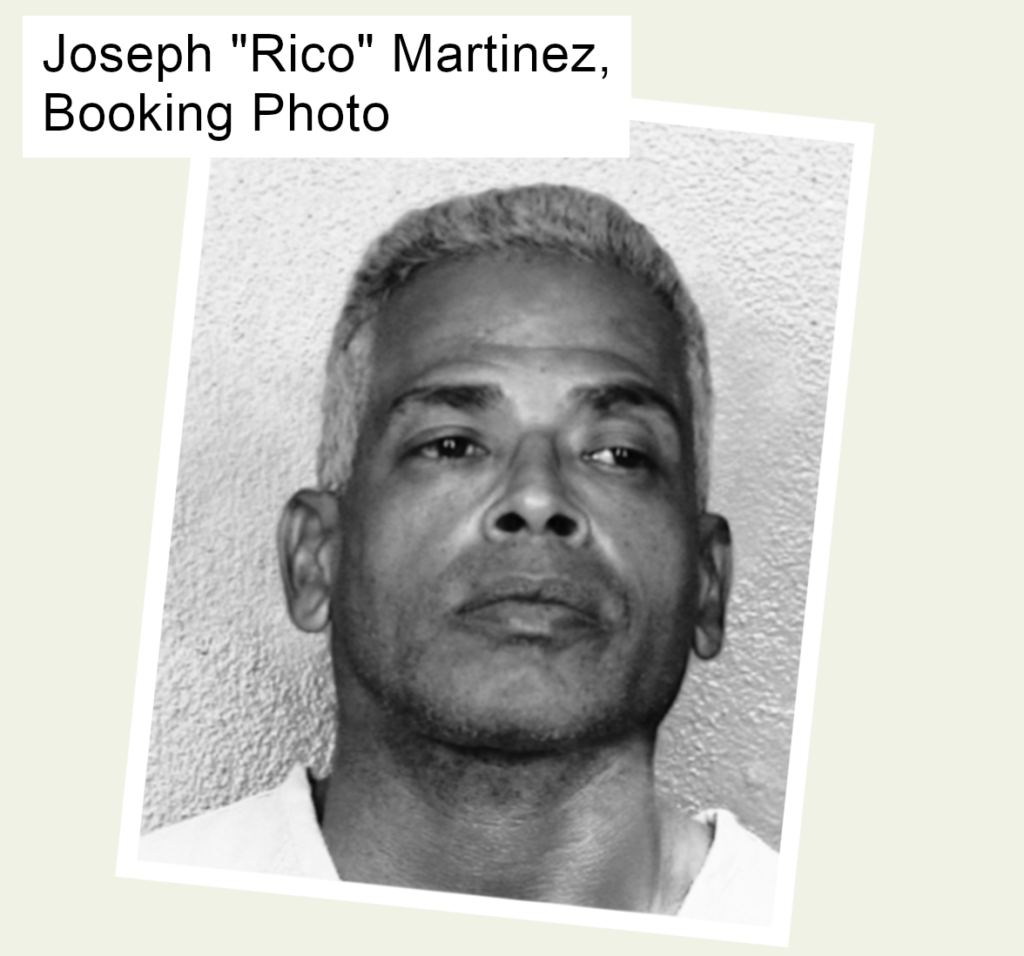

JOSEPH MARTINEZ sat, deep in thought, on a grungy bed in the overcrowded Ft. Lauderdale halfway house. At fifty, Martinez—who insisted he be addressed by his street name “Rico”—sported a gray ponytail and a muscular frame covered in crude prison tattoos and scars. He’d spent most of his adult life in and out of state and federal institutions for a variety of crimes. However, he was primarily a robber of banks and convenience stores. In fact, Rico had only recently been transferred from the Coleman Federal Correctional Complex to the federal halfway house in South Florida.

Although Rico liked to brag that he had “mad-potential,” in reality he was no more than a dimwitted thug with zero marketable skills. No sooner than he’d come to this conclusion did he grab his duffel-bag of clothes, sign for a three-hour-pass, and walked out of the halfway house with no intention of returning.

Now, I can’t say for certain where Rico met Vinessa—it may have been a seedy bar or a high-end strip club—but I do know that shortly after absconding from the Bureau of Prison’s custody, he and Vinessa “hooked up.” Rico had on a pair of thrift store jeans and a tight-wifebeater showing lots of ink. Vinessa, being a sucker for the “thug-life” look, was taken by him immediately. They did a dozen lines of cocaine in a restroom, had sex in a toilet-stall, and she decided he was a “keeper.”

Vinessa could always use the muscle—guys were always “jerking her around” regarding their outstanding debt.

Days after she and Rico met he was driving her charcoal gray four-door Mercedes, making collections for his girl.

EXPAND, THAT WAS Vitale’s solution to the question of what to do once they’d completed the second half of the $10,000,000 LottoNet raise. They’d completed the first raise and by August 2016, Vitale, Nuzzo, and the team were one million dollars into the next $5 million. At the rate the money was coming in Vitale knew they’d hit their goal within months. But he had a plan. “Why not expand the LottoNet brand into South America?” he mentioned to Gray over dinner. “It’s wide-open down there.”

“Sure, but how?”

Vitale’s Colombian-American attorney, James Evor’s,∗ associate, Alex Alonso had family in Colombia—affluent family with mega-connections throughout Central and South America. Vitale, Gray, and Evor agreed that Evor and Alonso would explore the viability of entering the market place.

Within days of their plane touching down in Colombia, the Colombian-lawyer and his associate met with the company that ran Colombia’s lottery, Gana (Spanish for “You Win”), and they were very interested. Evor and Alonso then spoke with the owners of the lotteries in Brazil, Costa Rico, Mexico, and Peru.

Latinka—the company that held the exclusive license to run Peru’s lottery—however, explained that, although, they were interested in a partnership, LottoNet would need to be approved by the governing commission which over saw the lottery, Beneficencia De Ica. Therefore, the Americans flew to Peru.

Following Evor and Alonso’s presentation to Beneficencia De Ica, several of the commissioners expressed how impressed they were, not only with LottoNet’s proposal, but with the technology. The app gave everyone in Peru with a wi-fi connection the ability to play the lottery—potentially quadrupling the market as well as the revenue.

“Tell me,” asked one of the commissioners, “does anyone involved with LottoNet have family in Peru?”

The question seemed strange, but benign. “No,” replied Evor. “Is that a requirement?”

“On the contrary.” In fact, the government of Peru is so inundated with nepotism, corruption is rampant. So much so that it had spread to every branch including the private lotto company, Latinka. Although Latinka was making tens of millions of dollars in profit per month the company hadn’t paid corporate taxes in twelve years.

Beneficencia De Ica hadn’t cancelled the company’s exclusive license, specifically, because Latinka was generating 1.8 million per day in sales tax and the Peruvian government was afraid to lose the revenue. Understand, the company’s license expired in one year, unfortunately, there wasn’t a competent company to take over the lottery that wasn’t corrupt with family relations of one sort or another. “However,” admitted the commissioner, “based on your presentation I believe that LottoNet could take Latinka’s place . . . Is that something you would be interested in?”

The two Americans made eye contact for a split second and Evor replied, “I believe our client would be very interested.”

The Beneficencia De Ica’s commission’s only requirement being “complete financial transparency. If you can guarantee us that we’ll issue LottoNet the license.”

“WE LOST OUR MINDS over the Peruvian lottery news,” confesses Vitale, while I scribble the quote in my yellow legal pad. We are at our usual table in the prison’s rec area and he is elated at the recollection.

Based on the news Vitale convinced Gray that it would be in LottoNet’s best interest to make him a twenty-two percent partner in the company. Gray couldn’t have agreed more. As such, Vitale immediately began “up selling” the Peruvians; he arranged for LottoNet’s license to include the exclusive rights to offer pre-paid casino cards, slot machines, poker, blackjack, et cetera.

“Owning the license to Peru’s lottery would give LottoNet the credibility to either expand into other Central and South American countries or at least convince the other lotteries to partner with us on the LottoNet app.”

Nuzzo and Vitale began discussing raises for Brazil, Colombia, Chile, Costa Rico, Mexico, Panama, Venezuela, and on and on. “The investors went nuts when they heard the Peru news,” Vitale says enthusiastically. They hadn’t even started the raise and clients were trying to invest. “I remember Nuzzo joked, ‘I feel like I’m sitting in the garage with Steve Jobs and Steve Wozniack.’ This is history in the making.”

DETECTIVE JUSTIN DAMERON with the Palm Beach County Sheriff’s Office Violent Crime Division stepped into the guest bathroom at approximately ten a.m., on October 25, 2016. The room was dimly lit, however, the detective could clearly make out Frank Nuzzo’s body laying in the bathtub. Oddly, he was clothed only in camouflage shorts with the pockets pulled out—as if having been searched.

There were small puncture wounds in his left bicep as well as several syringes lying haphazardly about the tile floor. Lividity had firmly established its presence. His pale, ashen skin and bluish veins only solidified the obvious, Nuzzo had been dead for days.

There were used needles in the bathroom wastebasket, noticed the detective, and drug paraphernalia throughout the home—a white box of new syringes were found in an adjacent room, an orange bottle filled with cocaine, and numerous other items. Someone had scrawled the saying Keep Doing Keep Getting on the mirror with black spray-paint.

Although there was a plethora of evidence pointing to a simple drug overdose, when Detective Dameron spoke with Nuzzo’s neighbor, Mark Joseph, he indicated that Kathryn O’Brian, Nuzzo’s fiancée, had left for Virginia several weeks earlier and—directly following her departure—there had been several suspicious individuals coming and going at all hours.

Specifically, the neighbor described a white male and female. “They were driving a dark gray or black four-door Mercedes,” he recalled. “They looked like trouble.”

In fact, the couple was so out of place in the exclusive gated community of Artesa, Mark jotted down the vehicle’s tag number—surveillance footage would later reveal that the Mercedes last exited the front gate at 3:16 p.m., on October 21, capturing both the male and female occupants’ image. The vehicle and tag were registered to Vinessa Noriega.

The following morning the detective spoke with Kathryn. During the call she admitted that Nuzzo had a serious addiction problem and stated his “dealers were Vinessa, Rico, and a guy named Tony. I can give you their cell numbers.”

Kathryn also pointed out, she’d been through the house, and discovered that someone had robbed the deceased. Over $30,000 in clothes and electronics were missing, in addition to $45,000 in cash.

With this information in hand, on October 26, Detective Dameron called Vinessa to speak with her regarding Nuzzo’s death. However, she was reluctant to talk; stating only that the deceased “was doing a lot of drugs the last time I saw him. That’s all I know.”

“When were you last at his residence?”

“Last Friday (October 21, 2016), I left around three o’clock,” she admitted, hesitantly. “Look, I can’t talk to you.” At that point Vinessa ended the call. Understand that both Rico and Tony wouldn’t return the detective’s messages and Vinessa refused to speak further.

During the CSI investigators’ search of the residence, they discovered a small caliber revolver, several live rounds, and one spent round—all of which were dusted for latent prints.

THAT SAME DAY, Vitale was driving home when Kathryn called and blurted out that Nuzzo was dead. Vitale hadn’t spoken with him in nearly a week. Presumably, Nuzzo had been working out of his house on the South American LottoNet raises. Vitale was blindsided by the news.

Kathryn explained that the Palm Beach Sheriff’s Office was investigating it as an overdose. However, Vinessa and Rico had been at the house on October 21 and suddenly, nearly $80,000 in cash and valuables were gone, and Nuzzo was dead.

The day before Nuzzo’s funeral Kathryn stopped by Vitale’s house. She was distraught over his loss. Nuzzo was a flawed individual, she admitted, “but he didn’t deserve to die. I know that Vinessa and that idiot Rico had something to do with it.”

“Don’t worry,” replied Vitale, attempting to console her. “They’ll show up. They’ll get what’s coming to ’em.” However, he didn’t truly believe there had been anything sinister about Nuzzo’s death. According to Vitale, Nuzzo had struggled with addiction, therefore Vitale assumed that he’d died an addict’s death.

Shorty thereafter, Detective Dameron closed the case—regardless of the robbery, the suspicious conversation with Vinessa, and the fact that several of the latent prints taken from the house belonged to a federal fugitive named Joseph Martinez (aka “Rico”). Despite all of the evidence to the contrary, the detective’s report specifically indicated Nuzzo’s death was an accidental overdose.

RICO WORE ALL BLACK when he entered the Ft. Lauderdale branch of Bank United, at 2:40 p.m., on November 10, 2016. He casually slipped beside a female employee and grunted, “I’m here to rob the bank.” He glance around the lobby at the other patrons. “If I see one fuckin’ cop I’m gonna start shooting customers.”

He motioned toward the teller stations and the employee escorted Rico behind the counter. There—per his demands—she quickly emptied out the drawer. Rico inspected the money for GPS trackers and exited the bank. He got less than $1,200.

At a Bank of America branch, four days later, Rico once again forced an employee to hand over the cash in her teller drawer—slightly over $3,200. He then exited the bank.

On November 19, Rico placed a single candy bar on the conveyor belt of a Publix Supermarket, leaned into the cashier, and said, “Gimme all of the money in the register.”

The nineteen-year-old male cashier assumed Rico was joking. He chuckled at the demand. “I don’t think so, bro.”

Rico then pulled out a knife—not a firearm, but a knife—and snarled, “Give me the money or I’ll blow your head off.”

The cashier scoffed and refused to give up the cash. This sent Rico into a furry, he lunged forward and stabbed the teen in the upper chest. Then turned and ran out of the supermarket.

Less than a week later, he robbed the Lauderdale Lake’s branch of Bank United. This time, however, he got away with nearly $3,800.

“YOU GIVE ME A DYE PACK,” Rico barked at the female Bank of America teller, on November 25, “and I’m gonna start poppin’ people off, you feel me?”

She nervously nodded her understanding and handed Rico $28,000 of the bank’s money—nine bundles of $2,000 and one $10,000 bundle. Rico quickly stuffed the cash in his right pocket and exited the building.

He climbed into a four-door Mercedes parked just outside the bank and tore out of the parking lot. At the same time a witness called in a description of the man dressed in all black and the vehicle. However, Rico immediately abandoned the Mercedes on a set of railroad tracks not far from the bank. While fleeing the scene, Rico seriously injured his knee.

Shortly thereafter the Broward County Sheriff’s deputies discovered the vehicle. They quickly set up a perimeter of the surrounding neighborhood. At the same time a tip was called in. The tipster stated he’d located a Hispanic male that matched the description of the bank robber.

As a result of his injury, Rico had collapse in the street outside the tipster’s house. Sure enough when the deputies arrived, Rico was sprawled out on the asphalt—unable to walk and reeling in pain—with $28,000 of Bank of America’s cash in his right pocket.

He was processed and transferred to the Miami Federal Detention Center to await trial.

THE PRESS CONFERENCE announcing LottoNet’s deal with the Peruvian government was attended by Evor and Alonso as well as numerous department heads and, of course, the press. There were questions and official photographs. The announcement was front-page news.

VITALE SWALLOWED a mouth full of scotch—he was in shock. He and Gray were seated at a table in The Lobster Bar, an exclusive restaurant and bar in Ft. Lauderdale, and Evor had just called with the news. It was official, they’d been issued the exclusive rights to operate Peru’s lottery.

“I can’t believe it,” gasped Vitale. He slapped his glass on the face of the table. “We own the lottery! We own the fucking lottery!”

Gray laughed. “This is amazing.” The purported profit, based on the current numbers were in the hundreds of millions and the projected number using the LottoNet paperless system was in the billions. “You’ve taken LottoNet to a level I never imagined.”

Now, according to Vitale, is when the real work began. He began looking for additional office space, furniture, computers, et cetera—gearing up to take the completed U.S. LottoNet raise and repeat the process in every country in Central and South America.

Just as things were about to kick into high gear Vitale’s probation officer called. She asked him to stop by the office the following morning for a random urinalysis test—it was no big deal. However, the next day, March 7, 2017, as Vitale pulled his Lamborghini into the probation office his cell rang.

“Don [Vitale],” blurted out one of his brokers using Vitale’s alias. The broker was sitting in his vehicle outside of the office. “The FBI just raided the office—they’re in there right now, dude.”

“Fuuuck,” replied Vitale. Instinctively, he knew that the UA test was a ruse. He promptly swerved the Lambo around, pulled out of probation’s lot, and punched the accelerator.

“THE FBI DIDN’T ARREST anyone,” Vitale informed me. However, the agents did seize everyone’s laptops and smartphones, in addition to the office computers, servers, and files. “I knew I was in trouble; there was the alias— which was more unethical than illegal—and the kick backs. At the very least, I’d violated my probation.”

Vitale spoke with his lawyer, Frank Maister. The attorney indicated that there had been a civil complaint filed, but it could, and most likely would become criminal any day.

Vitale decided that his best course of action was to go to Ecuador. “My girlfriend, Mariuxi, had family there,” he confides. As part of the license, LottoNet had opened a Peruvian corporation and a bank account. LottoNet-Peru was already online and ready to go. “Gray and I decided I could cross into Peru and run the LottoNet Corp., wait out the statute of limitations or negotiate a reasonable term with the federal prosecutor—probation or a fine or maybe even a couple of months jail time.”

THE GUY LEANING against the support column near the boarding counter glanced at Vitale one to many times. The Miami International Airport terminal was busy on March 25, 2017. Travelers were rushing to make flights, waiting for their seats to be called, and checking carry-on bags.

While Mariuxi casually flipped through a magazine, Vitale was nervously looking from person to person. Sure enough the guy near the counter snuck another peek at him and Vitale’s stomach began to churn.

The airline’s rep called Vitale and Mariuxi’s row and they approached the counter. Simultaneously, the man leaning on the column started walking toward them as did two other guys Vitale hadn’t noticed. All three of them stared directly at him and Vitale froze.

The men converged on he and Mariuxi. One of them thrust his FBI credentials in Vitale’s face and asked to see his passport. “You won’t be getting on that flight.”

“Why?” asked Vitale, feigning confusion. “What’s going on?”

“You’re being detained,” the agents replied, as a second law enforcement officer slipped a pair of handcuffs on his wrists, “on a complaint filed in federal court.”

Vitale was processed and taken to the Federal Detention Center in Miami. He was placed in one of the facility’s many housing pods with over one hundred and fifty other prisoners. Days after his “detention,” Vitale was indicted for mail fraud by the U.S. Attorney’s Office.

The government was insisting that LottoNet was a scam to defraud investors. A theory that Vitale’s attorney was vehemently disputing. Regardless—due to Vitale’s attempt to flee the country—the federal judge refused to grant him bond.

VITALE’S CELLMATE was getting a haircut—maybe a week or two into his incarceration—by another prisoner. A gray ponytailed bank robber with bad ink work. A real chatter box. “Yo. You look mad familiar,” he said to Vitale as he ran the clippers on his cellie’s head. “You from Lauderdale, bro?”

“Yeah,” he replied. Vitale introduced himself as “Joe” and extended his hand.

“Me too.” He laughed at the coincidence. “I’m Joe too—Joe Martinez.” He took Vitale’s hand and the two Joes shook. “But my friends call me Rico.”

Vitale recalled Kathryn’s description of Rico and Vitale thought, Holy shit, this might be the same guy. As a result, over the next month Vitale made it a point to spend as much time chatting up Rico as possible. They began working-out together, eating their meals together, and swapping stories.

Initially, they had very little in common, but Vitale was patient. Then, one day in the recreation area Rico mentioned, “I was fuckin’ crazy over this bitch, V. You might know her. She hung out at a lot of them high-end strip clubs.”

“V?” replied Vitale. “Vinessa? I know a chick named V. She dealt coke and weed to a bunch of my guys.”

“Yeah, bro, that’s my girl. She’s a little firecracker.”

Rico then went on and on about how he used to do collections for her and eventually they got onto another subject. A few days later Vitale worked Vinessa back into the conversation and Rico began rambling on about “fuckin’ this bitch until she couldn’t walk straight” and how he once had to “slap her ass around” and drag her into a hotel room by her hair.

As Rico told an endless parade of white trash stories Vitale began to hate him. He decided Rico was scum. A low life.