By Matthew B. Cox

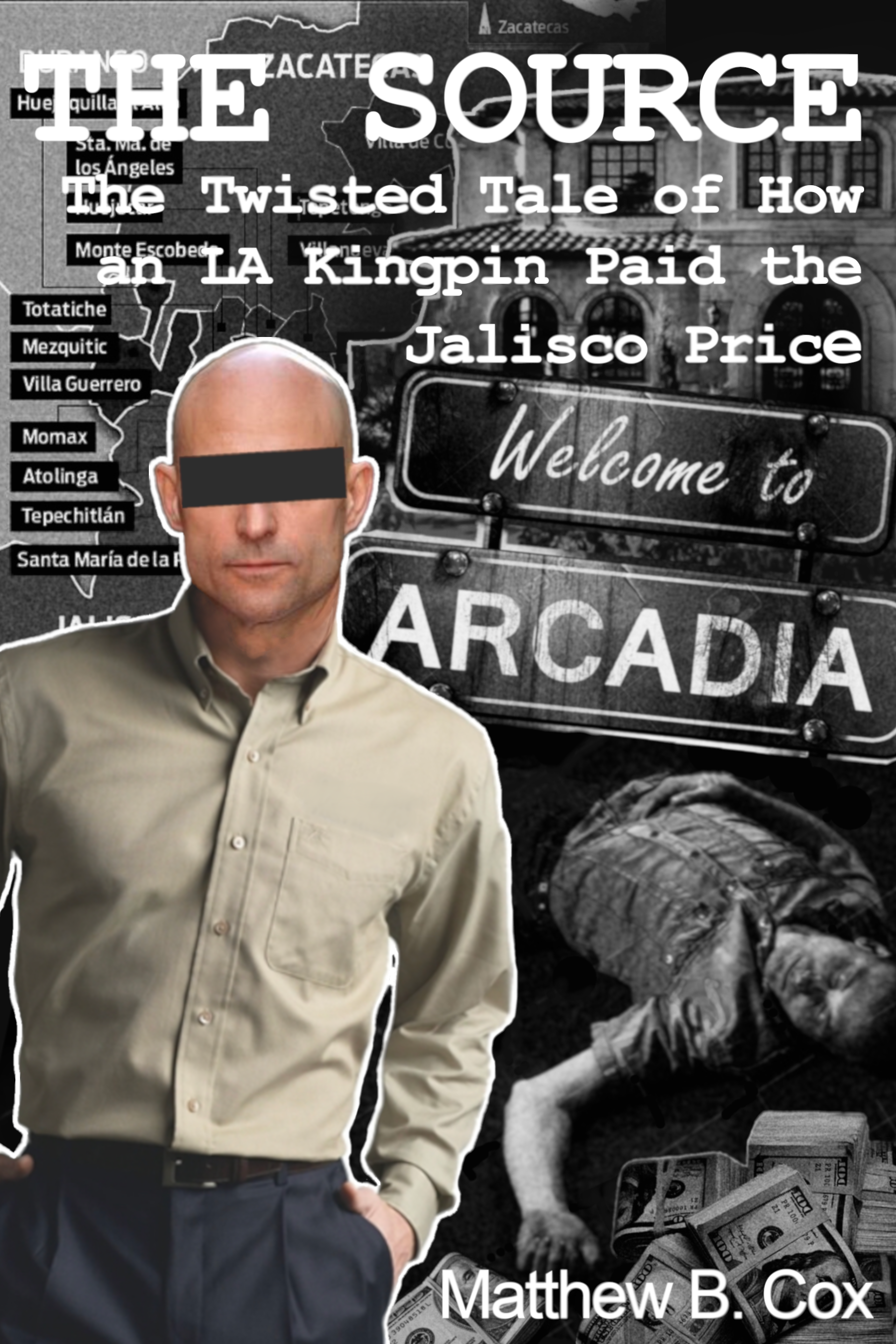

THE SLENDER HISPANIC male, veiled in a hooded sweatshirt and dark pants with short black cropped hair, stealthily approached the large beige house—a pistol tucked in the small of his back. It was December 12, 2011, in the city of Arcadia, a wealthy suburban Los Angeles bedroom community, nestled against the San Gabriel foothills. The man slipped around the corner of the three-car-garage, to the single side-door. There he pressed his weight into the door and frame, forcing it to give. The assassin stepped into the garage and was enveloped by the darkness where he waited for his prey.

Not unlike the character Carlos Ayala—the dashingly handsome top cocaine distributor for the fictitious Obregon Cartel—in the movie Traffic, Jose Antonio Parra lived in a large affluent home resting on its own private cul-de-sac called Kristi Court surrounded by lush manicured shrubs and a freshly cut lawn.

Just another well-kept Spanish-stucco multi-story home, revealing nothing of its owner. The neighbors knew only that the couple’s three young children played in the fenced backyard under their mother’s watchful eye. By all appearances their father was a successful businessman. Nothing indicated that Parra worked for the Sinaloa Cartel.

At its peak (between 2003 and 2008), the Sinaloa Cartel—taking its name from the Mexican Pacific state of Sinaloa, where the cartel was formed—was the largest and most powerful drug trafficking organization to have ever existed. The cartel’s leaders controlled a multi-billion-dollar network responsible for importing hundreds of tons of cocaine into the United States. Throughout that period, Jose Parra operated a Los Angeles-based wholesale distribution cell for the cartel and was a key operative in its American-based distribution network.

The assassin waited in the shadows while the Parra family attended Catholic mass at a nearby church. Just after 8:00 p.m. Parra pulled his expensive sedan into the garage. Once the family exited the vehicle the man emerged, pointing his weapon—his hood pulled taut around his head exposing little more than his brown eyes and a band-aid on his upper-left-check. Everyone was herded into the house where the intruder locked Parra’s wife and children in a first-floor bedroom.

Parra’s wife would later tell the homicide detectives she heard her husband and the intruder speaking briefly in the hallway—arguing about a debt owed to the cartel. A $2 million loss Parra insisted he wasn’t responsible for.

Then, the assassin fired four shots into Parra’s head from close range. He went to his death denying responsibility. Seconds later Parra’s wife and three young children found him lying motionless in a crimson pool on the cool marble floor.

A professional, cold blooded murder that to this day has not been solved.

MY NAME IS MATTHEW COX and I write true crime from inside the Federal Correctional Complex in Coleman, Florida—the largest prison complex in the United States. I’ve been incarcerated since November 16, 2006, for a variety of bank fraud related charges, and I’m one hundred percent guilty of them all.

Some inmates do their time working out in the institution’s recreation yard, others learn to play an instrument—it probably sounds silly—I write my fellow inmates’ stories.

In the fall of 2016, I was introduced to Cristiano Silva1, an inmate who had recently been transferred to the prison. Chris is tan with a wiry build and a burr haircut; a bright guy who quickly became known for having a keen legal mind. I had some legal questions regarding a manuscript I’d authored with a fraudster named Efraim Diveroli2—a true crime memoir chronicling Diveroli’s life as a teen-stoner-gunrunner who’d made millions selling weapons to the U.S. military, until the government turned on him.

[1 Name has been changed.]

[2 In the movie War Dogs, Jonah Hill portrays Efraim Diveroli.]

Upon his release from prison Diveroli published the book, under the title Once a Gun Runner…, then he turned around and sued Warner Brothers for theft of intellectual property. “But he never paid me for it,” I gripe to Chris during one of our first discussions on the subject. “The guy’s using the book that I wrote to sue Warner Brothers.” Diveroli had alleged that Warner Brothers had stolen the manuscript and used it to make the movie War Dogs. “The same manuscript that he stole from me. The guy’s a total scumbag.”

“The lack of payment alone shows Diveroli’s intent of never honoring your agreement,” replies Chris. He mentions needing to do some research in the institution’s legal library the following morning and offers to “check into it.”

He’s very professional—a rare characteristic among inmates. I don’t know anything about Chris or his case and I ask, “Were you an attorney on the street?”

“Nah,” he grunts, “drug dealer; what about you?”

“Con man.”

“Nice, nice.”

That’s how I met Chris Silva. Our interactions are typically short, clipped and direct. Above all, brutally honest. There’s simply no reason to bullshit one another.

The next day the drug dealer turned jailhouse lawyer informs me that based on Diveroli’s bad faith he feels I have a strong case. Additional research solidifies my standing regarding Warner Brothers; and Chris starts ordering court documents.

“You need to sue these guys,” says Chris, after receiving Diveroli’s Amended Complaint against the studio, “Diveroli and Warner Brothers.”

“I’m in prison; how am I gonna sue ’em? I don’t have any money to hire a lawyer—”

“I’ll do it!” he fires back. Chris has fought dozens of inmates’ criminal cases over the course of his tenure. However, following a transfer from Lompoc Federal Correctional Institution, California to Coleman FCC in Florida, he has ceased doing legal work for other inmates. “Civil law can’t be that much different than criminal.”

Using a thirty-year-old Swintec typewriter with no word processing function Chris begins litigating against Diveroli and Warner Brothers. During the course of the suit we began to spend more and more time together. At one point I ask him why he stopped doing legal work for other inmates?

“On the west coast the prisons are packed with drug cases,” he says. “That’s mostly what I focus on.” The answer was nonspecific, almost evasive. Incomplete. Based on our many conversations it felt wrong, so I kept probing him for details. Eventually he informs me that most of his past “clients” were Mexican cartel guys. “Specifically, members of the Sinaloa Cartel.”

BY THE TURN OF THE CENTURY, Ismael “El Mayo” (pronounced My-o) Zambada was the head of the Sinaloa Cartel. This was before the drug trafficking syndicate had achieved international notoriety. Back then, it was merely one of a handful of cartels operating out of western Mexico.

The Sinaloa Cartel was embroiled in full blown gang warfare; simultaneously fighting the Tijuana Cartel from the north and its more powerful ally, the Gulf Cartel in the east. While eachof the west coast cartels operated independently, they all struggled with the same problem: the rise of the Gulf Cartel. Drastic action was necessary before they were all swept under the control of their rivals.

Deep in the Sierra Madre mountains in Sinaloa, Mayo formulated a plan. With the help of Joaquin “El Chapo” Guzman, whom, along with Mayo, were the founders of the Sinaloa Cartel, they were able to persuade Ignacio “El Nacho” Coronel (the leader of the powerful organization controlling the Mexican state of Jalisco) to help them form a confederation among the Pacific coast cartels—a super-cartel. Mayo’s plan was to create a drug trafficking behemoth strong enough to mount a united front against the Tijuana and Gulf cartels.

In short order, Mayo, Chapo and Nacho entered into a strategic alliance with the leaders of other regional cartels throughout Mexico to create what became known formally as “el Cartel del Pacifico (the Pacific Cartel),” or, less formally, “el Federacion (the Federation).”

The Sinaloa Federation operated on a horizontal leadership structure. The cartel’s operatives each controlled certain territories, making up a decentralized network of bosses who conducted business through cooperative arrangements. Together, under the leadership of Chapo Guzman, the Federation launched offensives against the Tijuana and Gulf cartels.

Over the next few years the Sinaloa Federation eliminated all competition along the border from San Diego, California to El Paso, Texas. Seventeen ports of entry were firmly under their control. Each of the Federation’s major factions worked with one another to smuggle drugs into the United States, where American-based organizations then distributed the product throughout the country.

One of the primary drug smuggling routes between the United States and Mexico stretches from Tijuana to Mexicali in Baja California—a one-hundred mile stretch of the American border with six ports of entry, three of which fall within the metropolitan San Diego area. Mayo Zambada’s faction of the Federation controlled the San Diego-Tijuana corridor.

A high-ranking member of Zambada’s Organization—German “El Paisa” Olivares—controlled the flow of cocaine through the lucrative Tijuana plaza. German Olivares, known simply as “G” to his American associates, has been described by Justice Department officials as a “shadowy underworld figure” and a member of the Federation’s “upper echelon.” As Mayo’s top lieutenant, G coordinated the importation of multi-ton quantities of cocaine into the U.S. on behalf of the Zambada, Guzman and Coronel factions of the cartel.3

[3 German Olivares was indicted in Chicago along with Chapo Guzman, Mayo Zambada and other Sinaloa Cartel leaders in case number 09-cr-00383. See Exh. 1. See also Exh. 2: DOJ Press Release (Aug. 20, 2009). As of 2015, according to the Department of Justice, German Olivares remained a fugitive. See Exh. 3 at p. 3, paragraph 3.]

It was Jose Parra in Los Angeles who took delivery of G’s shipments. Parra operated a distribution cell for Mayo and G—distributing thousands of kilograms of cocaine, worth hundreds of millions of dollars. He was also responsible for coordinating the delivery of shipments to the Federation’s other distributors in Los Angeles including, among others, Juan Garcia.4

[4 See Exhibit 4: Excerpt of Government Memorandum, U.S. v. Juan Garcia, No. 1:13-cv-03040- GHW (S.D.N.Y.) (Dkt 10), at p. 24 n. 7 (quoting DEA Agent’s Testimony identifying “G” (German Olivares) as “one of the main bosses of the organization in Mexico.”).]

“THERE ARE CARTEL GUYS here,” I inform Chris in January 2017. We’re walking the half-mile track in the prison’s rec yard while discussing my civil case, “they might be Sinaloa.”

“Yeah, but I’m not interested in picking up any law work right now.” We walk in silence for a while and he continues, “I worked a guy’s case in Lompoc; an idiot, named Juan Garcia, whose sister married Nacho Coronel’s nephew.” Although the bulk of the cartel’s operations are decentralized, their internal hierarchy is very much a family business. Fathers, brothers, sons, nephews, cousins and in-laws occupy the top positions in most of the organizations. As insurance, everyone holding a key position knows their associates’ family. The potential for murderous reprisals is ever-present. “Because of this lying-Lilliputian,” grumbles Chris, “the whole case went sideways.”

THE AIRBRAKES HISSED as J & M Express’ tractor-trailer—bound for New York—rolled out of the Inland Empire truck-stop, one of dozens of massive asphalt parking lots scattered throughout Southern California packed with big rigs—all virtually indistinguishable from one another. Juan and his driver, Jesus Dominguez, had just loaded one hundred and eighty kilos of the Federation’s cocaine into a clavo (or secret compartment) within the rig’s bowels.

A smug smile crept across Juan’s face as the trailer’s taillights grew faint. The first generation Mexican-American’s diminutive frame only accentuated his over inflated ego. It was more than a simple Napoleon complex. Juan was arrogant.

Perhaps, in that moment, he had a right to be. Juan had multiple drivers traversing the lower forty-eight’s Interstate system—containing all manner of goods—however, his bread and butter was trafficking the Federation’s cocaine. Only days earlier one hundred and eighty kilos had been delivered to Chicago and an additional one hundred and eighty more were en route to New York.

It was the fall of 2003 and Juan Garcia was at the top of the trafficking game.

Due to the cartel’s interconnected web of family relations, he’d been given a position within the organization ran by Nacho Coronel’s nephew, Ricardo Madrigal Barajas—Juan’s cunado (brother-in-law) and best friend. Using tractor trailers, equipped with hidden compartments, Barajas and Juan were responsible for distributing the Federation’s cocaine to the Bernales Organization in Chicago and the Moreno Organization in New York, both of which were headed up by Barajas’ cousins: Cuco Bernales and Johann Moreno. Between the Spring of 2001 and the Spring of 2002, the cunados transported in excess of 2 tons of product without so much as a hiccup. Then, on March 25, 2002, Barajas was arrested in Indiana for drug trafficking.5 Luckily, Juan managed to avoid being indicted. Regardless, the trafficking operation had come to a screeching halt.

[5 See Unites States v. Ricardo Madrigal Barajas, No. 3:02-cr-00046 (N.D. Ind.). Please note that Barajas was represented in Indiana by David Arredondo, a prominent Los Angeles drug attorney. See also Exh. 5: Affidavit of Attorney Arredondo (Jan. 2005) at ¶16.]

By this point Mayo, Chapo and Nacho had formed the Sinaloa Federation. The factions these men controlled coordinated their smuggling activities through the Federation’s cooperative arrangements and relied on one another’s American-based networks to distribute the cocaine and facilitate its transportation to regional hubs for delivery to wholesale customers. Basically, their networks were interconnected; cocaine supplied by Chapo’s faction might be smuggled through tunnels controlled by Mayo’s people and transported throughout the United States by Nacho’s Organization.

Shortly after Barajas’ arrest, Juan was contacted by Parra’s right hand man, Jose Salinas. The Federation needed him to fill the void left by the arrest of his cunado. Within months Juan had purchased two slightly used Freightliner tractor-trailers—which he then had modified with a hidden compartment designed to remain undetectable by Department of Transportation inspectors—and opened J & M Express with a truck driver, Jesus Dominguez. He put together a network of drivers willing to transport tons of cocaine to Chicago and New York. Juan and “Cuco” Bernales formed a partnership; took over responsibility for Barajas’ operation and began shipping cocaine throughout the United States.

Like clockwork, every month to six weeks Parra and Salinas dropped off three hundred kilos for transportation. The product was stored at Juan’s stash house—an upper middleclass residence in the conservative suburb of Rancho Cucamonga.

The taillight disappeared into the distance. Dominguez would arrive in New York within five days; he would drop off the product and pick-up $4 million owed from the previous month’s shipment. Juan had it all figured out. During the course of the past ten months he had made millions for both the cartel and himself.

“THIS GUY DIDN’T EARN his position,” Chris informs me with a hint of disdain. Juan hadn’t risen through the ranks, learning the drug trade through trial and error. He hadn’t dodged indictments and watched his peers go to prison. He hadn’t learned the lessons that only came with experience. Unlike Chris, who started his drug career at nineteen with a single ecstasy pill, “Juan’s sister married him into the business. The guy drove a canary-yellow Hummer with over a dozen flat-screens in it and blew tens of thousands of dollars in strip clubs; which is fine in Vegas, but you don’t do that in your own backyard.”

“He did all the things a professional doesn’t do,” I interject for clarity.

“Precisely,” agrees Chris. “He thought he was Chapo Guzman.”

IN THE AUTUMN OF 2003, the police received a 9-1-1 call regarding a domestic dispute at a shabby apartment complex in Bellflower—a routine call for the area. Parra and two of his associates where seated at the dining room table in Parra’s stash house located within the complex. Methodically, the three men counted out drug proceeds—segregating G’s money into ten thousand-dollar stacks held in place by a thick rubber-band. Hundreds of thousands of dollars were heaped into a duffel bag lying on the carpet.

When the Los Angeles Sheriff’s Department deputies arrived at the complex they mistakenly went to the wrong apartment. Parra and his henchman were unprepared when the officers banged on the front door; seconds later they forced their way into the apartment—in search of the domestic dispute victim—catching Parra and his accomplices in the act.

The three men were arrested. Parra’s associates were subsequently released on bond. Parra, however, was on state parole in addition to being an illegal alien. Therefore, Parra was held in custody for violating parole; he remained in custody until the following spring.6

[6 See Exh. 5.: Attorney Arredondo Affidavit at ¶11-12]

Weeks later—on December 9—while transporting forty-six kilograms of Parra’s cocaine to New York7, Juan’s driver, Dominguez, was pulled over by the Illinois State Police. The officer asked Dominguez to consent to a search.

[7 These were kilos of cocaine that Parra had left stored at Juan’s stash house at the time of his arrest.]

It wasn’t the first time Dominguez’s rig had been randomly chosen for inspection—none had ever come close to finding the clavo. As a result, he confidently volunteered a search of the rig. This time, however, the officer noticed a slight inconsistency in the living-quarter’s cabin space betraying a concealed compartment containing nearly one million dollars’ worth of cocaine. Dominguez was promptly arrested for drug trafficking.

Shortly after the DEA arrived at the police department Dominguez agreed to cooperate.8 He admitted to transporting in excess of 1,000 kilos from Los Angeles to New York in addition to shuttling over $12 million in drug proceeds over the preceding 11 months.

[8 See Exh. 6: DEA Report (Dec. 16, 2003).]

Within hours Dominguez made several calls to Juan that were monitored by the agents. Those calls, coupled with his statement, gave the government probable cause to obtain a wiretap on Juan’s cell phone nine days later. From that point forward—December 18—everyone that Juan spoke with became a target of the DEA’s investigation. Their phones were then subjected to wiretaps and the individuals they called then became targets as well. Out of this overlapping, interconnected spider-web of wiretaps emerged dozens of potential targets consisting of thousands of hours of highly incriminating recordings.

Following Dominguez’s last call, he vanished off Juan’s radar. However, during the lag-time between the monitored calls and the wiretaps, Juan arranged—through Juan Ordenes’ company (Debee Do Trucking)—to have a second driver, Cleofas Vasquez, transport one hundred and eighty kilos to Cuco in Chicago. Cuco then had the shipment rerouted to his cousin, Johan Moreno in New York. There he picked up $4 million and delivered it to Juan in LA.9

[9 See Exh. 7: exert from Sergio Medrano v. United States, 2015 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 24123 (S.D.N.Y. Feb. 27, 2015).]

On February 4, 2004, Vasquez picked up a vehicle transport loaded with automobiles—one of which was a Mitsubishi Montero containing a clavo with nearly $1 million concealed inside.10 Based on the information obtained from the wiretap on Juan’s phone the DEA arranged to have the New Jersey State Police pull over the tractor-trailer, at which time the DEA identified the Mitsubishi out of several vehicles, which the state police promptly seized.

[10 Notably, the Montero was supposed to have been loaded with $2 million, however, there was a timing issue with the money Moreno owed. Juan made the decision to have the driver return to LA with the available cash and collect the remaining $2 million owed on a later trip.]

The detectives then discussed the situation with Vasquez, who vehemently denied having any knowledge of the Mitsubishi’s contents stating, “I’m just a driver, man.” At that point a detective handed him a business card, said, “Tell the Montero’s owner to call me,” and then released him.

Once he was back on the road, Vasquez called Juan; in a panic he conveyed the news about the seizure. The following morning—at 7:32 a.m.—Juan called Salinas11 and said, “They’re after us, dude.”

[11 See Exh. 8: Excerpts from DEA transcripts of the wiretapped conversation between Juan and Salinas.]

“Uh?” Salinas grunted, half-asleep.

“They are after us,” repeated Juan. “They got that guy. The one with the money.”

“No way.”

“I’ll call you back, dude,” said Juan. “I’m all fucked up right now.”

At this point, between the Dominguez and Vasquez seizures, Juan had lost over $2 million of the cartel’s cash and cocaine and all he had to show for it was a business card. He was frantic. Desperation was setting in.

“THE THING ABOUT THE CARTEL is they don’t like losses, but they’ll deal with them,” says Chris as we sit at a table made of concrete and rebar, sweating in the merciless Florida humidity, “provided the losses aren’t suspect—that was the problem.”

Juan had no explanation as to how the DEA knew about the Mitsubishi or why the driver hadn’t been arrested. Nor could he account for why there wasn’t at least $2 million in the truck.

“So, the cartel was going to kill ‘im?”

“Well,” Chris rocked his head from side-to-side in contemplation, “yes and no. If you can convince them that your actions were reasonable, typically they’ll let you work off the loss.”

The source of the cartel’s cocaine originates from the fields in the Andes Mountains and the jungle labs of Colombia. The product is then transported to Venezuela; there, it’s distributed in multi-ton loads to various Mexican drug cartels. Back in the mid-2000s, a kilogram of cocaine would cost $2,000 in Venezuela, with a minimum purchase of 1,800 kilos. Each time the product is moved it incurs additional costs. In Acapulco, that same kilo costs roughly $4,000. The closer the cocaine gets to the border the more it costs. Once the product reaches Mexico City the amount increases to around $7,000. By the time it gets to the Tijuana border, the value of that kilo is somewhere in the neighborhood of $9,000.

“But you’ve gotta get it across the border.”

“That’s where G comes in,” admits Chris. G controls multiple tunnels for the Sinaloa Cartel, which are used to transport drugs into southern California—a service they provide to all of the organizations operating in Sinaloa controlled territory for a modest $2,500 per kilo fee, known as piso. “For Parra, LA prices ran around fourteen thousand dollars per kilo. Juan and Cuco were paying Parra eighteen-five per on a consignment basis. Now if you lose the product you’re on the hook for that material, but there’s always the chance they’ll let you pay it back atthe Tijuana price.” In a lull between Chris’ statement I jot down “Tijuana price” and he punctuates his statement with, “assuming they don’t kill you.”

THE SMALL RESTAURANTE was closed, however, there were well over two dozen serious men—holding fully automatic weapons—standing guard scattered about the entrance, perimeter and inside. It was Spring 2004, the area surrounding the restaurant in Guadalajara, Jalisco’s state capital, was desolate—the local policia had been told not to enter that section of the city. Cartel business.

Day’s earlier, Salinas had called Juan with the news he didn’t want to hear, “G wants to see you in Guadalajara.” Parra had been deported to Mexico and he and G wanted “an accounting.”

As Juan, Cuco and Moreno stepped into the restaurant Nacho Coronel—the head of the Federation’s Jalisco faction—G and Parra were seated at a table with several other men. None of them looked happy.

Standing in front of Nacho, G and Parra, the scene played out like an inquisition, with one relentlessly harshly worded accusation after another, while half a dozen grimfaced body guards stood poised to put a bullet in their heads.

G—who was there representing Mayo—one of the founders of the Sinaloa Cartel—wanted to know precisely how the DEA knew to take the Mitsubishi. “Why wasn’t the driver arrested?” he asked the trio. “You got an answer for that?”

“Maybe someone out of New York is cooperating.”

“Well then how do you explain the [earlier Illinois] seizure?”

Juan stammered out one pathetic excuse after another—each one more implausible than the next—as Cuco and Moreno stood silent. With each of Juan’s excuses he tossed another shovel full of dirt onto their graves.

“You took it upon yourself to sell my product—not your product, my product—which you lost,” interjected Parra. “That cost us eight hundred thousand!” Juan then had another million seized by the DEA. He was currently short an additional $2 million. “Not your cash, my cash,” spat Parra, as he flipped the detective’s card over in his hand—suspiciously examining the thin cardboard rectangle. “You owe us three point eight million dollars and you hand me a business card. How’d this happen, Juan?”

At this point Nacho interrupted, pointing out to G that Juan was his nephew’s cunado, and Cuco was his nephew’s primo (cousin). “These are good men. They’ve done a lot of work for us, they didn’t steal the money.”

Everyone in the room knew their relationship to Nacho was the only reason they were still alive, but there was no guarantee they were going to stay that way.

“Maybe, maybe,” before Juan could come up with an excuse that would potentially get them all executed and buried in the desert, Cuco stepped forward and replied, “Look, we can’t account for what happened, but we’re here; and we’re gonna get you the three point eight. We just need some time.”

Juan, Cuco and Moreno walked away from that meeting with their lives. Shortly thereafter—as a show of good faith—Cuco returned to Guadalajara and transferred the title to his ranch in Mexico to G. He and Juan then began frantically scraping together the funds owed. In a moment of desperation, Juan called Parra and pleaded with him to give them “a break on the price.” They wanted Tijuana prices of $8,500 per kilo on at least the ninety-one kilos that had been seized in New York and Illinois. But Parra refused.12

[12 See Exh. 9: Excerpt from the DEA wiretap.]

“Let’s see what G has to say,” said Juan; asking to discuss the matter with G directly. “If G wants to, then it’s a go, alright?”

“Well no,” replied Parra, “it can’t be done.”

Regardless, of Parra’s objection, Juan called G. However, the call did not go well and Juan was specifically told they could not pay Tijuana prices.

Miraculously—within a month—Juan and Cuco managed to come up with the remainder of what they owed Parra, G and Mayo. Once they’d piled the bundles of bills into Juan’s Hummer the partners stared into the rear of the vehicle. The cash represented everything they had and they were about to hand it over to Parra.

Cuco turned to Juan and said, “One day, we’re gonna kill this motherfucker.”

“HE ACTUALLY SAID THAT?” I ask.

“Yeah,” admits Chris. “Juan said Cuco was adamant Parra had to go—he was just biding his time.”

Once they cleared the debt, Parra suggested that Juan setup a new trucking company. He bought another tractor-trailer and had it outfitted with a clavo. He was back in business. Then, just prior to the arrival of an eight hundred kilo shipment—three hundred of which were allocated to Juan and Cuco—the DEA executed arrest warrants13. They snatched up Salinas on July 8, 2004 and, two days later, they grabbed Juan, followed by Ordenas, Vasquez and Juan’s cousin, Ernesto Garcia.

[13 On June 22, 2004, a federal grand jury in the Southern District of New York returned an indictment charging Juan and five others with participation with conspiracy to distribute cocaine. US vs. Juan Garcia, No. 1:04-cr-00603 (S.D.N.Y.).]

UNDER THE FLORESCENT LIGHTS in a conference room at the Metropolitan Detention Center in Los Angeles, David Arredondo slid a DEA Report across the table to Juan during their second attorney-client meeting. Arredondo, a prominent Los Angeles drug attorney who served as counsel for Nacho Coronel’s Organization, tapped his pointer finger at the phrase “Jose (LNU [Last Name Unknown]) CI” on the report.

“Your buddy Jose’s the informant,” he said—indicating Parra was a “CI” or confidential informant (as it turned out, that report was nothing more than a summary of Salinas’ statement to the DEA; wherein Salinas indicated his belief that Parra was a CI). “I’ve had my suspicions about him since that Baltimore case.”

“No, that can’t be right. He’s G’s guy,” replied Juan. Despite the lawyer’s certainty, Juan refused to accept it. “Jose’s too high up.”

Within days of that meeting Juan spoke to another inmate named Mamucas, who told him he’d been busted directly after purchasing fifty kilos of cocaine from Parra and Salinas. “I didn’t get but a couple miles and they pinched me,” he said. “I think Jose [Parra] set me up.”

In addition to Mamucas’ arrest, Parra’s brother-in-law had earlier been indicted in Baltimore for conspiracy to distribute over one hundred kilos.14 Plus there was Fortunato Franco, another of Parra’s distributors—he’d gotten in excess of one hundred kilos seized in LA, as did Jesus Montano and Abel Zendejas. They were busted with twenty-six kilos purchased from Francisco “Chico” Perez, another one of Parra’s distributors, while Basquel, one of Salinas’ customers, got picked up for fifteen kilos. Despite all of these seizures and arrests, Parra had never been charged.

[14 See Exh. 5 at P8-10.]

This, coupled with Arredondo’s statements that Parra was a “CI” convinced Juan that Parra was responsible for his predicament. Suddenly it all made sense. Parra had been secretly working with the DEA. As a result, Juan’s attorney, David Arredondo filed a motion to suppress the wiretap evidence based on the fact that the government had an informant, Jose Parra, operating within the organization and therefore lacked the necessity to obtain the wiretaps.

During arguments, Assistant U.S. Attorney Marc Berger stated that Arredondo’s claim was “baseless conjecture” and unfounded “speculation.” The prosecutor insisted that the government had no knowledge of any Jose Parra. AUSA Berger argued that “[i]f Mr. Arredondo wants a hearing, he has to provide some sort of factual basis to believe that there was an informant named Jose Parra. [Arredondo’s motion] basically is wild speculation… [I]t’s ridiculous.”15

[15 See Exh. 10: Government’s Memorandum of Law in Opposition (Feb. 1, 2005); See Exh. 11: Transcript of Feb. 4, 2005 Hearing.]

Shortly thereafter, the motion was denied, and with it, all hope of going to trial. The government had hundreds of calls incriminating Juan and Salinas and there was nothing they could do. On March 29, 2005, Juan appeared before Judge Baer and pled guilty to Count One of the Superseding Indictment. A few days earlier, Salinas had done the same.

Prior to their sentencing, however, Ordenas, Vasquez and Ernesto Garcia proceeded to trial. On April 20, 2005, DEA Agent Keuler testified regarding two of the wiretapped calls. The agent testified that on May 13, 2004, three months after the Vasquez seizure, the DEA had intercepted a call between Juan and someone named “Jose” that indicated that Juan owed “Jose” and someone named “G” a considerable amount of money stemming from multiple seizures of cocaine and drug proceeds.

Ordenas, Vasquez and Ernesto Garcia were all found guilty.

Then, at Juan and Salinas’ sentencing on July 13, 2005, Arredondo, in an attempt to mitigate Juan’s role in the conspiracy, told the judge16, “[i]t’s interesting that the guy, [Jose Parra, the] central figure of this whole thing was never…arrested, never apprehended.” He explained that Parra was the “supplier” of the cocaine and the “prime mover of this case. For some reason he is still out there, even though in California he was arrested and released.”

[16 See Exh. 12: Excerpts from sentencing transcripts.]

“Well,” replied the judge, directing the question to AUSA Berger, “what does the government have to say about all that?”

“I’ll start with this name, Jose Parra, which seems to keep surfacing but really only from Mr. Arredondo’s mouth. This name was never mentioned at trial, as best as I can remember. No case agents have ever heard of this individual.” The prosecutor continued with “[i]t seems that what [Juan and Arredondo are] trying to do is create this imaginary individual who is the big kingpin whereas, in reality, the two kingpins are sitting right behind me.”

Based on the government’s denial of Parra’s existence, the court determined that Juan and Salinas were the most culpable participants in the conspiracy. “If there was a leader,” said the judge to Juan, “you and your co-defendant are it.”

He then sentenced Juan to 292 months; Salinas subsequently received 264 months.

“WHAT ABOUT PARRA and Cuco?” I ask Chris.

At the time of Juan’s arrest both Cuco and Parra had been in Mexico. Shortly thereafter both of them returned to California. “Cuco took over responsibility for Barajas’ trafficking operation in Los Angeles,” replies Chris. “Before Juan ever even appeared before the judge in New York, the operation was firing on all cylinders.”

Both Nacho and G were impressed by how Cuco had handled himself and the debt owed by him and Juan; that resulted in fast-tracking Cuco’s position within Nacho’s organization. In fairly short order he was moving a considerable amount of product and interacting with not only Parra, but G as well. Cuco’s star was on the rise.

“When you were out there—in Los Angeles—did you know G?” I ask. At this point I know some of the particulars regarding Chris’ case. They’re not pretty. “Were you at that level?”

“Yeah,” he sighs, “I knew ‘im. He wasn’t Mayo’s top lieutenant back then, but still pretty important.”

Cristiano Silva was a drug trafficker long before he was a jailhouse lawyer. He began distributing MDMA (ecstasy) in the Beverly Hills area back in the late 1980s. Within a few years, his drug activity escalated to cocaine and crystal methamphetamine (“ice”); the bulk of the cocaine and, later, methamphetamine used to produce the “ice” was supplied by the Sinaloa Cartel. Although Chris’ contact was subordinate to G, he had participated in various meetings with high-ranking representatives from the cartel who had tried to persuade Chris to shift the “ice” manufacturing operation to Mexico.

As the operation grew, the quantities, the money and the stakes got higher. According to law enforcement, Chris’ drug activity helped create the “ice epidemic” and led to the murder of an FBI informant.

Chris’ drug activity sparked investigations by the FBI, the DEA, the California Bureau of Narcotics Enforcement and the Los Angeles Police Department. Ultimately, he was indicted in the latter part of the ’90s for conspiracy to distribute cocaine and crystal methamphetamine, operating a continuing criminal enterprise, and murder in the furtherance of a drug conspiracy, among other charges.

In 2000, Chris, then 30 years old, was convicted and sentenced to over 30 years in prison. Over the next decade he bounced between institutions within the federal prison system.

“When I first fell,” says Chris, “it quickly became clear I didn’t have any natural allies.” He wasn’t affiliated with any gang or cartel, nor was he physically big enough to stand alone against the various factions competing for power within the maximum-security prison where he was being housed. As a result, it became important to make himself indispensable to the inmate population. He needed to be someone that everyone would need at some point. “There aren’t a lot of articulate inmates. So, guys started coming to me, they’d ask me to help them write a letter to their lawyer or their judge. That turned into quashing warrants for drug traffickers, many of whom were Mexican nationals.”

The mindset of a Mexican-national prisoner is vastly different than that of an American inmate. An American prisoner wants to get his sentence cut to time served. The Mexican-national inmate, however, only wants to get his sentence reduced low enough to be eligible for a treaty transfer back to Mexico. Unfortunately, none of that’s possible as long as there are outstanding U.S. warrants.

“What type of warrants?” I ask.

“It could be anything—DUI, failure to appear in court—anything.”

He then moved on to challenging inmates’ sentences—by then he had begun developing the skills necessary to litigate habeas actions (also known as a Section 2255 motion) and various other motions seeking sentence reductions. “Once a Mexican-national has less than eight years remaining on his sentence, he’s eligible for a treaty transfer,” says Chris. “If he’s got money—which most of these cartel guys have—it’s not unheard of to have a corrupt Mexican prosecutor file bogus charges against one of their citizens in federal prison to get him extradited to Mexico to face those charges. Of course, once he’s on their soil they drop the charges and the guy walks, after he gets resentenced in accordance with Mexican law.

“So, over the period of what, a decade,” I say, “you educated yourself on criminal law and post-conviction litigation.”

“A little less than that, but yeah.”

By the time Chris was transferred to the low security prison at the Federal Correctional Institution in Lompoc, California, in 2010, he was primarily focusing on the more wealthy prisoners cases which, for the most part, meant interacting with cartel members. He had become a conduit between the inmates and their high-end defense attorneys; over the years Chris had developed claims that some of the most prominent criminal defense attorneys on the west coast had litigated.

“The way it works is this,” Chris tells me, “aside from the difficulty involved with communicating with an inmate—many of whom barely speak English or have a formal education—if an inmate pays an attorney one hundred thousand to file a section 2255 motion the more time that lawyer spends learning the facts of the case, the less profit they make.” For example, if there’s two hundred hours of DEA wiretap recordings that need to be reviewed—at $600 an hour—that’s two hundred billable hours. Not to mention, court appearances, researching case law, reading transcripts, drafting motions, et cetera. It doesn’t take long before the attorney is working for free. “Any lawyer that tells you that’s not a factor is lying.”

To overcome this obstacle, Chris became a conduit between the inmates and their attorneys. He began spending time with the inmate-clients, reviewing their cases, and identifying claims and marshalling together the facts which could be used by their outside counsel. “I became someone that the inmates respected and trusted more than their attorneys; and the lawyers valued my input because I could spend the time necessary with the prisoner to fully learn the facts of the case in a way no attorney could never do.”

JUAN HEARD about the new hotshot jailhouse lawyer shortly after Chris stepped off the bus in May 2010. Over the preceding year Chris’ legal prowess had culminated in four inmates receiving sentence reductions and the immediate release of a fifth inmate.

When Juan approached Chris outside his housing unit that summer, Chris was in the process of working on Eloy Sanchez-Guerrero’s case, a Sinaloa Cartel trafficker convicted of being the head of a massive multi-ton cocaine conspiracy who’d been sentenced to three hundred and sixty months. Chris was working with David Cheznoff’s office—Guerrero’s prominent criminal defense attorney out of Las Vegas—to prepare Guerrero’s reply to the government’s response to his habeas action.17

[17 See Exh. 13: Letter to David Cheznoff (Sept. 7, 2010); Ultimately, Cheznoff was able to obtain a reduction of fourteen years in Guerrero’s sentence.]

Chris arranged to meet with Juan the following week. At that time, while walking the track encircling the low security’s rec yard, Juan laid out his conspiracy theory regarding Jose Parra acting as a confidential informant for the DEA and how the government had covered that up by denying Parra existed. “Is that something I can use?” asked Juan. “They lied, Parra’s real.”

There were a couple of errors committed by Juan’s attorney at sentencing; both of which could have been used to file a habeas action alleging ineffective assistance of counsel. “However,” Chris told Juan, “at this point, you’re time-barred.” As an inmate convicted of a federal crime Juan had to file his 2255 motion within one year of the date his sentence became final which, in Juan’s case, had been five years earlier. Barring certain circumstances—which didn’t apply to Juan—any claims that he were to bring would have been time-barred. Chris explained to Juan that Congress and the courts had placed a higher value on the finality of a conviction over justice. “There’s nothing you can do.”

Over the next six months Juan bounced some ideas off Chris in connection with his case, but none of them amounted to a viable claim. Then, eight months later, on January 18, 2012, Juan caught up with Chris in the housing unit’s quad. He’d just found out that during his codefendants trial, one of the DEA agents had testified regarding Jose Parra and his involvement in the drug conspiracy.

“Does that help?” asked Juan. “Can I bring a claim?”

“Maybe,” replied Chris with a shrug. In his opinion federal prosecutors are very good at manipulating the facts of a case. They do so, however, through omission, rather than resorting to telling bold faced lies. Chris explained that if Juan could prove the government knew (or should’ve known) Parra existed, “then you could attack the sentence based on newly discovered evidence of prosecutorial misconduct, assuming your attorney wasn’t aware of the factual predicates underlying your claim. If that’s true, you might have a chance, but I’d need to see your codefendant’s transcripts.”

Knowing there was a chance Chris might end-up referring Juan to Cheznoff, he asked some of the paisas about Juan’s ability to pay the high-end lawyer’s fee. Everyone he spoke with told him Juan’s word was good. “He won’t have no problems paying,” said one cartel member. “His partners got the Guadalajara Plaza; he’s Jalisco New Generation.” Another member told Chris, “That’s one stand up mother-fucker.”

By the time the transcripts arrived, on April 30, 2012, Chris was deep into another prisoner’s case—as well as assisting his own attorneys to prepare another one of his appeals. He gave the documents a quick read, and, sure enough, a DEA agent named Keuler had testified about a wiretapped conversation between Juan and an individual named “Jose.” It appeared, based on the transcripts, that not only did Juan owe this “Jose” a large sum of money, the wiretaps also established that “Jose” was the source of the cocaine and that Juan was his subordinate.18

[18 See Exh. 14: Transcript of Trial Testimony of DEA Agent Keuler.]

Although the transcripts didn’t state Parra’s last name, it confirmed that Juan didn’t concoct an imaginary individual, nor was he the kingpin of the organization. Most importantly, it proved the government misled the court when Assistant U.S. Attorney Berger stated that none of the DEA’s agents had “ever heard of this individual.”

“You might just have something here,” said Chris.

Between Juan’s defense lawyer, David Arredondo, and Manual Lopez (an earlier post-conviction attorney), it took several months to track down the case file; and an additional couple months to produce the materials Chris needed.

During this time, Chris and Juan had numerous discussions concerning Juan’s claim that Parra was a DEA informant. The issue at hand was twofold, one, whether Parra actually existed and, two, whether he’d been a federal informant. Chris had no intention of squandering his credibility with Cheznoff’s office by presenting Juan’s theory that Parra was an informant unless Juan could convince him Parra was the source.

“It doesn’t make sense that Parra’s the source of the DEA’s information,” explained Chris, during one of their many walks on the rec yard. Primarily because the millions of dollars in cocaine and cash seized by law enforcement was Parra’s. “He could be the biggest snitch on the west coast,” he continued, “there’s one person he would have never told on; he would have never told on himself.”

“My lawyer told me he was the source!” shrieked Juan, his little arms gyrating wildly in agitation.

“The notion that this guy was setting up his own loads is absurd,” Chris barked back. Parra certainly wouldn’t have set up Juan and Cuco knowing they owed him several million dollars that he owed G. “You guys were his best customers!” And if he was the DEA’s source, why hadn’t Parra disclosed the location of Juan’s Rancho Cucamonga stash-house? “From a trafficking perspective, what you’re saying makes no sense! And, from a law enforcement perspective, it makes even less sense. The authorities would have pulled Dominguez over outside LA; they would have never allowed this guy to drive two thousand miles—with a million dollars’ worth of cocaine—before pulling him over in some mid-western state. And there’s no way a New York prosecutor would’ve blatantly lied to a New York judge to conceal the existence of some LA informant.”

In addition to those discrepancies in Juan’s theory, Parra had been incarcerated when both the Dominguez and Vasquez loads were intercepted. In Chris’ view this made it virtually impossible for Parra to have been the DEA’s source of information.

SOMETIME BETWEEN late November and early December 2012, Chris was watching CNBC in his housing unit when Juan approached. “What if Parra was dead?” he casually asked. “Could we use that to prove he was an informant?”

Chris gave him a sideways glance, immediately feeling something wasn’t right. “What do you mean dead?”

“If he were dead,” replied Juan with a shrug.

“Depends on how he died, was he hit-by-a-bus, dead, or bullet-in-the-back-of-the-head, dead?”

“From what I heard,” whispered Juan, “bullet.”

Chris pointed to the exit with his chin and they moved the conversation outside—away from the other inmates—and asked for specifics. Juan knew few. He then advised Juan that if he, or his people, had anything to do with Parra getting killed, Chris couldn’t have anything to do with his case. “This is serious,” he told Juan. “I’m here on a contract killing of an informant case. I know how seriously the authorities take these matters. If you or your people had anything to do with this guy getting killed, under no circumstance should you initiate any attack on your sentence.”

“No, no, we didn’t have nothin’ to do with it,” he replied. According to Juan, Parra’s murder was completely unrelated to his case. “There were plenty of people that wanted Parra dead. The motherfucker had it coming; but we didn’t do it.”

The fact that Parra may have been murdered was the first indication that he may have been a DEA informant. There would have to be media and law enforcement reports that could be used to disprove the government’s claim that Parra was an imaginary individual.

In January 2013, the case file materials arrived.19 With the exception of Attorney Arredondo’s statements to the judge, there was not a single document indicating Parra existed, much less was the DEA’s source.

[19 See Exh. 15: Letter from Manual Lopez to Juan Garcia (Dec. 31, 2012).]

“I SPENT FIVE DAYS reading every single piece of paper,” Chris tells me, “and not once did Parra’s name appear. The wiretap applications were clearly a result of Dominguez’s cooperation, thus blowing up Juan’s theory that his investigation had emerged from an earlier Parra related investigation originating in Baltimore.” In fact, everything indicated it was Juan that had unwittingly gotten everyone busted by continuing to use his cell phone after Dominguez and the load of cocaine disappeared. “This was where Juan’s lack of experience led to everyone’s detriment.”

“What did Juan say?”

“His ego wouldn’t allow him to accept it.” Juan refused to believe that he’d been responsible for the losses or for destroying half a dozen people’s lives, including his own. “After I read the wiretap applications, I knew that all of these men were in prison because of Juan’s incompetence.”

Regardless, it was becoming more and more apparent that Juan’s arrogance was hindering his ability to make rational decisions.

“EVERY SINGLE PERSON you spoke with on that phone—other than Parra and Cuco—is doing fifteen to twenty years in prison,” Chris told Juan, after reviewing the documents. “You’re all over the wiretaps. You’re the source of the DEA’s information.”

“That’s not true,” he growled. “It wasn’t me it was Parra. They’re protecting him.”

“The only reason why Parra wasn’t indicted along with you was because he had the good fortune of being in jail while you were blowing up everyone else’s phones.”

Based on the information contained in the file Chris told Juan he didn’t feel comfortable approaching Cheznoff’s office with his claims. He explained that there was no reason for Juan to spend $150,000 on Cheznoff when there was very little chance he’d get over the time-bar. Regardless, Juan wanted to attack his sentence based on Parra being the kingpin and the prosecutor misleading the court.

In Chris’ opinion federal judges don’t make a point of over sentencing inmates. They typically weigh the evidence and make well thought-out decisions based on all of the pertinent facts. Now, are mistakes made? Certainly. But Chris doesn’t believe that most judges act maliciously. Despite the untimeliness of Juan’s claim there was a small chance that the judge would find a way to correct the sentence if he believed that the Parra related facts had affected the outcome of Juan’s sentencing. So, Chris agreed to prepare and file Juan’s motion.

“But I’m telling you, Juan, if you had anything to do with Parra getting killed I can’t be involved with your habeas action,” he said. “I’m not letting you jeopardize my case by getting me dragged into this.” Chris was in the middle of his own appeal and he had a very strong issue before the Ninth Circuit. He was confident he’d win his appeal and that he would get resentenced. However, he also knew once the government realized that Parra had been murdered that might spark an investigation in which both Juan and he would be interviewed. “You can’t put me in a position where I’ll have to lie for you. I won’t do it.”

“I had nothin’ to do with it,” Juan insisted. “He was a snitch, lots of people wanted him dead.”

Over the next six weeks, Chris prepared Juan’s motion. As additional evidence to support Juan’s motion—Chris asked his mother to mail him four sets of the media articles regarding the murder reported in the Los Angeles Times, the Pasadena Star News, and the LA Weekly.20

[20 See Exh. 16: Homicide Report, LA Times (Dec. 22, 2011); See Exh. 17: Police Release Sketch, Seek Clues in Arcadia Slaying, PasadenaStarNews.com (Dec. 13, 2011); See Exh. 18: Jose Antonio Parra, Arcadia Father, Murdered by Home Intruder as Wife, 3 Kids Listen From Bedroom, LA Weekly (Dec. 13, 2011).]

On April 14, 2013, he was walking across the compound when Lieutenant Johnson with the prison’s Special Investigative Services (SIS) unit stopped Chris.

“Silva (Chris),” said the lieutenant, “what’s with all this Jose Parra stuff?” Someone in the mail room had caught the multiple sets of articles and forwarded them to the SIS unit. “This doesn’t have anything to do with your case, does it? I mean, you’re here on a murder case.”

“No, I’m doing some legal work for one of the paisa’s, Juan Garcia. Those are exhibits in support of his 2255 motion.” Chris then summarized the case for Lt. Johnson and convinced him to release the articles to Juan.

As Chris and Johnson parted ways, the lieutenant wheeled around and asked, “I’ve gotta question for you. How’re you gonna prove that your guy’s Jose Parra is the same Jose Parra in the LA Times article?” It was a good question. In California the name Parra is nearly as common as Williams or Smith. “There’s gotta be hundreds of Jose Parras.”

“THAT WAS A VARIABLE I hadn’t taken into consideration,” Chris told me; and there was a good chance the government would take the same position.

“You had the articles.”

“Yeah, but prosecutors are very good at twisting facts. We needed something concrete, something definitive.”

Following the release of the articles, Chris completed the habeas petition and Juan filed it with the court.21 In his motion, Juan claimed that his due process rights had been violated because he had been sentenced on the basis of false or inaccurate information. He also claimed that the government had engaged in prejudicial misconduct that had undermined the integrity of his sentencing. Specifically, Juan claimed the prosecutor had made false statements which had worked to Juan’s detriment. He also claimed the government had improperly withheld exculpatory information.

[21 See Motion to Vacate Sentence, U.S. v. Garcia, No. 1:13-cr-0304 (S.D.N.Y.) (May 1, 2013).]

Days after the filing, Judge Baer ordered Juan to show cause as to why the motion shouldn’t be dismissed as untimely.

In response, Chris filed declarations from Juan and his former defense counsel, David Arredondo, in support of Juan’s timeliness arguments.22 As they waited for the court’s decision, the issue of connecting Juan’s Parra to the deceased Parra weighed on Chris’ mind.

[22 See Exh. 19: Declaration of David Arredondo (June 2013).]

“We needed someone that could make that connection,” says Chris. “Someone beyond reproach. That’s when I came up with the idea of contacting the homicide detectives. According to the newspapers, they didn’t seem to have any leads; so, if Juan offered to give them some background information regarding Parra’s drug activity…they’d definitely come out to see him.” Chris had been through a homicide investigation and he was familiar with the basic procedures involved. “I knew the first thing the detective would do was establish whether Juan knew the deceased—using a photo lineup. Once Juan picked out the correct Parra, we’d be able to subpoena the detective to prove that Juan’s Parra and the deceased were one and the same.”

“And Juan was okay with this?” I ask.

“Not really,” snickers Chris. Initially Juan was concerned that he could get in more trouble for the additional drug activity he would have to discuss, “but once I explained that wasn’t possible, he was all for it.” On July 17, 2013, Chris wrote a letter to the homicide bureau of the Los Angeles County Sheriff’s Department 23 “I kept telling Juan, ‘Once we mail this, they’re definitely coming. So, if you had anything to do with this guy getting killed, this is the wrong route to go.’ But he said, ‘Mail it,’ so I mailed it.”

[23 See Exh. 20: Letter from Juan Garcia to Los Angeles Sheriff’s Homicide Bureau (July 15, 2013).]

DETECTIVE BRIAN SONEMAKER was waiting in the conference room when Juan was led in by SIS Officer Macias. It was around 8:30 a.m., September 12, 2013, the officer sat in a plastic chair off to the side of the rectangular table in the center of the room. Juan took the chair opposite Sonemaker.

All Juan had been instructed to do was provide the detective with some background information regarding his drug activity with Parra. Initially, things went as planned. Sonemaker’s irritation that Juan didn’t have anything concrete on the murder was obvious, but he’d asked Juan to identify Jose Parra’s photo—just as Chris had predicted—which proved that Juan clearly knew the Jose Parra being discussed in the newspaper articles. The detective even acknowledged that the authorities were aware that Parra had been a big-time drug trafficker in LA. That was the entire purpose of the meeting. After that, however, the interview went off script.

“Something’s not right here,” griped the homicide detective. “I think you’re lying. I think you know who’s responsible for Parra’s murder.”

“How would I know?” replied Juan. He hadn’t seen Parra in nearly a decade. “I don’t know anything—”

“Bullshit,” grunted Sonemaker. He glanced around in frustration and added, “Why do you think he was killed?”

That’s when Juan’s ego got the better of him. Despite being specifically instructed not to mention his theory Parra was a confidential informant, Juan blurted out: “Come-on, you know why.”

“No, I don’t know why. You tell me.” Other than Parra’s wife overhearing the discussion over the cartel’s money, there is very little likelihood the detective had any solid leads.

“Come-on, you know he was a snitch,” snapped Juan. He added, a “CI,” and made air-quotes with his index and middle finger. “You know.”

Sonemaker went cadaver stiff, all movement stopped and the room went morgue quiet. It was clear the detective had no leads that indicated Parra was an informant, for one very specific reason: Parra wasn’t an informant. “What’re you talking about?”

At this point Juan lost his cool and shrieked, “Don’t bullshit me! You know what I’m talking about. He was making cases all over the place for you guys, Baltimore, Chicago, New York, LA.” Juan jabbed his finger toward the photograph of Parra and spat, “He’s the reason I’m in prison! He cost me and my friends millions; he got us all busted!”

Juan began ranting about how the U.S. attorney had given his lawyer some “paperwork” indicating Parra was a CI. “Read my paperwork,” Juan kept saying, “Read my motion, it’s all in there.”

Sonemaker reared back and said, “It sounds like you and your friends had something to do with the murder.”

“No, no,” stammered Juan, “lot’s of people wanted him killed, lot’s of people.” But it came out weak and ripe with insincerity. He knew he’d said too much. He shut down and went silent.

Juan tracked Chris down at his housing unit and regurgitated the catastrophic blunder he’d made during the interview. Chris could feel the color drain from his face when Juan admitted to telling the detective that Parra was the reason he was in prison and that he’d cost Juan and his friends millions.

“Oh my God,” gasped Chris. “I told you not to mention your theory that Parra was a CI! You just gave them evidence of motive; evidence of intent.” Chris told Juan that the detective’s next move would be to call his prosecutor and confirm Parra wasn’t a confidential informant in his case. “Then he’s gonna have the BOP pull all of your phone calls.”

“But he was a CI.”

“You’re the only one that thinks that! You and that crackpot lawyer!” Juan’s only saving grace, Chris told him, was that he didn’t have anything to do with the murder. “Once he figures out Parra’s not a CI, he’s going to put it together with the fact that you erroneously believe he was; thus, making you the only one with a motive.”

From that point on, Chris began referring to Juan as “goofball” to himself and to his fellow inmate/legal assistant and typist (Scott Robinson).

Chris worked as the Lieutenant’s orderly—cleaning up and emptying the trash in the administration’s offices. As a result, he knew most of the prison staff, so Chris made it a point to “bump” into SIS Officer Macias later that day. He casually asked how Juan’s interview had gone.

“Not good,” replied Macias. “Your little friend lost his composure.” He gave Chris a sideways glance and almost whispered, “You sure this guy didn’t have anything to do with that murder?”

“Says he didn’t.”

“Well, he sure looked guilty.”

A week after that conversation, Officer Macias confided in Chris that Detective Sonemaker requested the BOP pull all of Juan’s recorded calls. Macias volunteered that if the detective asked, he was going to have no choice but to mention Chris was doing Juan’s legal work. Chris told Macias that he had no problem talking with the detectives.

On October 22, 2013, Juan received the government’s response to his habeas action.24

Chris read it the following day and it was devastating. The government had not only disclosed the wiretap transcripts to Juan’s attorney, they had also provided Juan a copy via the warden at the Metropolitan Correctional Center; and they had multiple exhibits to substantiate their claims.25

[24 See Exh. 4: Government’s Opposition (Oct. 15, 2013).]

[25 See Exh. 21: Letter to Warden of Metropolitan Correctional Center.]

As Chris read he could feel anger welling up inside. Juan’s claim alleged that the government engaged in prejudicial misconduct that undermined his sentencing. However, the wiretap evidence supporting his claims had been provided to both Juan and his defense attorney. Because Juan hadn’t raised the claim at sentencing or on appeal, he was now “procedurally defaulted,” i.e. unable to present the issue to the court. And because they had had this evidence in their possession all along, Juan’s claims were also time-barred.

“Did you have the wiretap transcripts?” asked Chris. He showed Juan the exhibit of the letter to the warden. “They sent them to you at MCC [Metropolitan Correctional Center] prior to sentencing.”

Juan shook his head emphatically while mumbling, “No, no, I never saw ’em.” Then he stopped and said, “Oh yeah, they sent me something, but I never looked at it.”

“Why not?”

“My attorney told me he had everything handled.”

Juan’s entire argument was based on the government improperly withholding evidence—that they clearly had turned over—and making false statements during his sentencing—that Juan’s attorney could have disputed at the time.

“That’s it, you’re time-barred. It doesn’t matter whether you looked at it or not, you could have. You’re dead in the water,” said Chris, shaking his head in disgust at the colossal mess Juan had created. “And that’s the least of your problems.”

“What do you mean?”

Exhibit A to the government’s response was a 6-page report documenting Juan’s cooperative efforts with the DEA following his arrest.26 The report summarized the post-arrest statement Juan had provided, admitting his involvement in the conspiracy and implicating his coconspirators: Cuco, Moreno, Salinas and Parra, among others. Chris couldn’t help but simmer in the hypocrisy. Juan, the “standup guy,” had actually made monitored calls for the DEA to Cuco in an attempt to get him and Parra busted. He’d been strutting around for the last decade calling Parra a “snitch” and a “CI” when he’d actually cooperated.

[26 See Exh. 22: DEA Report of Interview of Juan Garcia.]

In addition to Juan implicating himself and everyone else, thereby undermining his defense, the government had also indicated that Parra wasn’t an informant; once and for all proving that Juan was the only one with a motive to murder Parra.

“You’re this close,” growled Chris, holding up his hand with his index and thumb half an inch apart, “to getting charged with Parra’s murder.”

“I can’t be charged!” snarled Juan defiantly, “I’m in prison. I have an alibi.”

“Don’t you understand? It’s a conspiracy charge! You don’t have to be the shooter to be charged for conspiracy. I’m here for a murder I didn’t personally commit. They’ll put it on you!” yelled Chris. “They’ll hit you with conspiracy.” In most cases the government tries to prove that the accused had a motive to commit the crime, “but you’ve already admitted to having a motive.”

The next morning, around 11:30 a.m., Chris noticed Juan standing in the “chow line.” His eyes were bloodshot; his hair was a mess. They took a walk around the compound and Juan confessed, he hadn’t slept at all the previous night. “I couldn’t stop thinking about what you were saying yesterday,” said Juan. “I know you’re gonna be upset, but just listen. I don’t wanna get charged with Parra’s murder.” He indicated he hadn’t been “straight-up” with Chris about the murder. “I know why he was killed; and who had it done.”

“Fuck,” hissed Chris. He could feel a ball of anxiety forming in the pit of his stomach.

“What did you do?”

Not long after Juan’s sentencing he’d started broadcasting his belief that Parra was a DEA informant, but no one in the Federation’s leadership believed him. Parra had been too crucial of a part of the organization. Then, in 2008, there was a series of drug busts by the DEA. In Chicago, Cuco’s brother-in-law was caught with over three hundred kilos of cocaine. There was over five hundred kilos intercepted by the DEA in Ontario, California, where G maintained his stash-house; and additional loads were seized in LA, resulting in over a ton of Sinaloa Cartel cocaine being seized. Product that G’s man in Los Angeles—Parra—would have been responsible for.27 Suddenly it seemed possible that Parra might have been compromised.

[27 Between 2005 and 2008 the Flores brothers operated a Chicago-based distribution cell for the Sinaloa Cartel. In 2008, however, they began cooperating with the DEA against Mayo, Chapo and G, among others. According to the FBI and the DEA, in 2008 the Flores brothers were responsible for providing the FBI and DEA with the information that resulted in the seizure of approximately two tons of cocaine in Chicago and LA—product belonging to Mayo’s and Chapo’s factions of the Sinaloa Federation. See Exh. 3: DOJ Press Release.]

In 2009, Ricardo Barajas got word to Juan requesting he send him any documentation regarding Parra acting as an informant. Juan immediately fired off a letter summarizing Attorney Arredondo’s statements about Parra being a confidential informant, along with his court transcripts and the DEA Report stating “Jose (LNU) CI.” Juan had the materials delivered to Barajas in Guadalajara. For Barajas and Cuco, that document along with their attorney’s statements solidified Parra’s guilt. The information Juan supplied sparked a contentious meeting between G and Parra (who operated within Mayo’s Faction of the Sinaloa Federation) on one side and Barajas and Cuco (who operated under Nacho’s Faction).

After presenting the proof of Parra’s cooperation to G—according to Juan—Cuco and Barajas demanded that G make them whole and return the $3.5 million that Cuco and Juan had reimbursed him for years earlier.

“And I want my ranch back,” said Cuco, he then pointed to Parra and spat, “and thatmotherfucker dead.”

“That’s not gonna happen,” replied G. “He’s not responsible for the losses.” G drew a line in the sand, refusing to accept that Parra was an informant and the meeting ended in an impasse.

That would have been the end of it, however, the following year, in July 2010, Nacho Coronel was killed in a shootout with the Mexican military. The following day his brother was murdered. The Coronel clan blamed Chapo for orchestrating the assassinations. Nacho’s nephews—one of whom is Ricardo Barajas—immediately broke away from the Federation and formed an organization calling itself “Nueva Generacion (New Generation).” The New Generation Organization then formed an alliance with the Milenio Organization, headed by Nemesio Osequera Cervantes (“El Mencho”). Together the two organizations became known as the Cartel de Jalisco Nueva Generacion (the “Jalisco New Generation Cartel”).

In the spring of 2011, the New Generation Cartel declared war on all other Mexican cartels and immediately unleashed their military wing, known as the Matazetas. One of its cells was headed by Cuco Bernales. Later that summer, under Mencho’s leadership, the New Generation achieved international notoriety when thirty-five dead bodies of rival cartel members were dumped in a wealthy suburb of Veracruz. According to Juan, that was the work of Cuco’s group.

By that autumn, the New Generation had achieved its goal and seized control of the state of Jalisco, including its capital, the mega-city of Guadalajara. The New Generation had expanded its operation-network from coast to coast in a matter of months. The New Generation then formed an uneasy alliance with the vestiges of the Sinaloa Cartel. The agreement allowed for each organization to traffic product through the other’s territory, in addition to the use of the New Generation’s maritime ports and Sinaloa’s drug smuggling routes.

Cuco inherited control of the plaza in Guadalajara when his faction of the Matazetas prevailed in the power structure for control of the city. Once he’d asserted his control over the territory, one of Barajas’ and Cuco’s first order of business was to have Parra killed.

On December 12, 2011, Parra and his family were ambushed at their home in Arcadia—he was executed as his wife and children stood in the adjacent room. He went to his death denying responsibility.

“Cuco had ‘im killed in retaliation for cooperating with the DEA and losing the money,” said Juan, “and getting me busted.”

“Are you out of your fuckin’ mind?” Chris exploded. “Why’d we file the motion if you knew your people were good for this murder?” Juan insisted he’d only learned about the murder after the fact. However, he was concerned because he’d been the driving force behind labeling Parra an informant. “Are you crazy?”

“Cuco killed Parra; he’s crazy. He killed Chico (one of Parra’s distributors) too.” However, the authorities have never recovered Chico’s body. Juan confessed that Cuco was good for at least three additional murders in Chicago, one in Arizona, and hundreds in Mexico. “But I didn’t kill anybody.”

“You sent the report to a homicidal-maniac responsible for hundreds of murders!” growled Chris. “You then lied to a homicide detective about the murder.” Who at that very moment was possibly listening to Juan’s calls. “This is a fuckin’ disaster!” Chris snapped at Juan and stomped off. Once inside his housing unit he immediately wrote a memo to himself documenting the time and date.28

[28 See Exh. 23: Memo to Self (Oct. 24, 2013).]

Juan had caused an innocent man to be killed and there was the very real possibility that the homicide detectives would put it together. At a minimum, Juan had obstructed the homicide investigation. Chris’ fear was that he’d eventually be interviewed and during that interview he would be placed in a position where he would either have to lie or implicate Juan; and he had no intention of lying.

On the evening of October 27, 2013, Chris met with Juan to discuss how they could undermine the government’s claim that Juan had been the leader of the cartel’s distribution in LA. “Were there any additional cases or seizures after you were arrested,” asked Chris. “Something we can point at to show that you were just a cog in Parra’s much larger conspiracy; that the cartel’s distribution network continued without you.”

“Sure,” replied Juan, “there was a case in Detroit, involving Johann (Moreno’s) brother-in-law and Carlos Medina. It was a big case; a few hundred kilo conspiracy.” He told Chris that there were additional cases, “I’ll get ’em for you.”

The next morning, Juan handed Chris a note identifying multiple cases that he had identified showing the distribution continued without him.29

[29 See Exh. 24: Juan Garcia’s Handwritten Note.]

“I remember a couple,” he said. Juan pointed to the “Cicero” entry on the handwritten note and explained, “This one’s Cuco’s compadre—he was charged in Chicago on a five hundred kilo conspiracy. Jose supplied all that product.” Juan then pointed to the 2008 “Joliet” entry, “This one’s Cuco’s brother-in-law, he got busted with three hundred and eighty-five keys; I know Jose set this one up too, bro. That’s over six million on this one bust alone. That’s the one that caused Ricky (Barajas) and Cuco to come around to my way of thinking about Parra. That’s when they started believing me.”

“EARLIER THAT YEAR I’d won my appeal,” Chris tells me. He was waiting to be brought back to court to have what he believed would be a considerable amount of time cut from his sentence; and the homicide detectives—at that very moment—were making arrangements to interview him regarding Juan’s case. “I was in exactly the position I’d been trying to avoid.”

“Why?” I ask. “Other than a motive—which in and of itself doesn’t mean Juan did anything, homicide didn’t have anything.”

“You don’t understand, Parra was killed in the furtherance of the drug conspiracy that Juan was in prison for,” Chris explains. The Supreme Court has held that a person can be held criminally liable for the actions of a coconspirator if those actions were reasonably foreseeable. Even assuming Juan’s statements about a lack of foreknowledge were true, he could still have been charged because he should have known that his actions would result in his associates killing Parra. “He should’ve realized how Cuco would react… Plus, there was another issue, Juan talked on the phone all the time.”

Depending on the institution, inmates are limited to 300 minutes a month of phone time. However, wealthy inmates often buy poorer inmates time by using their PIN numbers to access their accounts. Juan confided he was very worried about the detectives listening to his calls, because after Parra had been killed he was speaking with a friend from Guadalajara who let him know Parra had been “taken care of.”

“Do you know when that call was made?”

“Yeah, I can identify the specific phone call,” says Chris. “Even worse, when he told Juan about the murder, Juan didn’t say, ‘Why’d you do that?’ or even act shocked; instead he said something along the line of, ‘Good. Fuck him.’ Essentially Juan made an expression of approval. He was really worried about that call.”

CHRIS WAS CLEANING Lompoc’s Lieutenant’s Office on November 14, 2013, when Officer Macias mentioned that the homicide detectives were asking questions about Juan. Macias wasn’t sure it was going to be possible to keep Chris’ name out of the investigation.

“You’re doin’ all this guy’s legal work,” said the officer. “They’re gonna want to talk to you.”

Chris shrugged it off telling him, “I’ve got attorneys. If they want to talk to me they can call them.”

Hours later, however, when Chris mentioned the conversation to Juan, it sent him into a panic. He was certain that he’d be indicted. That’s when he asked Chris, “What would you do?”

Chris told Juan that when he was first arrested, both the FBI and DEA had asked him for his assistance. Unfortunately, he was young and arrogant. He made the fatal decision not to cooperate, his coconspirators, however, had no such loyalty and, subsequently, he became the focus of the investigation. Ultimately, this lead to Chris being charged with conspiracy to murder an FBI informant.

“It was the biggest mistake of my life,” he admitted. “You have a chance to get out in front of this thing. You get a lawyer to contact the homicide detectives and you come clean with them.” By cooperating in the murder investigation Juan not only had a chance to avoid being charged as a conspirator or for having obstructed the investigation, he would likely have received a sentence reduction for cooperating. “I know that’s not what you want to hear, but—”

“No,” he interrupted, “I’m not gonna do that.” Juan didn’t want to put his family at risk, he explained. He also planned to get back into trafficking drugs upon his release. “I’m gonna need these guys.”

“Are you out of your fucking mind? You’re nine in on a twenty-five-year sentence. These guys aren’t going to be around when you get out,” Chris shot back. “With the exception of Mayo and Chapo, the shelf-life of a narco is a few years tops. How much longer do you expect these guys to be alive? To be able to avoid arrest?” He explained that the moment these guys were arrested they would cooperate.

“That’s not gonna happen,” scoffed Juan, “they’re in Mexico.”

“That doesn’t mean anything!” Over the last decade numerous drug kingpins had been apprehended in Mexico; nearly all of whom had been extradited to the United States and immediately began cooperating with federal law enforcement. “The U.S. isn’t Mexico, they’re all looking at life sentences; their only option is to give up murders on American soil.”

Over the next two weeks the conversation dragged on. Chris tried to convince Juan to cooperate. “It’s the smart move,” he told him over and over. It finally came to a head on December 1, when Chris said, “You can’t come to prison and keep making the same mistakes that got you here—that’s what you’re doing.”

“Look, I can’t, okay.”

“Why?”

“Because!” blurted out Juan, “I told them to kill him. I knew it was gonna happen!” After the formation of the New Generation Cartel Juan’s partners agreed to kill Parra for Juan. “I’m the one that sent word to Ricky (Ricardo Barajas) and he told Cuco to kill him!”

Juan had been so convincing in his denial of having any prior knowledge of the murder that Chris was stunned by the admission. Once he regained his bearings he told Juan that was all the more reason to cooperate. “At a minimum, Ricky and Cuco know that you ordered the hit. Both of them have right-hand-men. Not counting the shooter, that’s at least four men who could implicate you in this murder. It was also inconceivable that they’d have killed someone as crucial as Parra without clearing it with Mencho and Mayo first. “That’s at least eight guys that know you’re responsible.”

“And G,” admitted Juan. “G was the only one who knew where Parra lived.”

The implication that the upper echelon of the two major cartels in Mexico knew Juan was responsible for Parra’s murder was sobering. It was only a matter of time before they were arrested and extradited. “The minute anyone of them touches American soil,” said Chris, “they’re gonna turn on you.”

“No, no, that’s not possible,” mumbled Juan, in a daze. “They’re too high up. They’re all protected.”