”DEA!” GROWLED THE TALL, lean black woman as she approached the crowd of patients meandering outside the pain clinic’s entrance. A mixture of nearly a dozen federal agents, state health department investigators, county sheriff deputies and detectives marched in unison behind her. It was 8:00 a.m., mid-November 2008, in South Florida. The agent held up her Drug Enforcement Administration credentials high enough for all to inspect, but she gave no indication of breaking her stride. None of them did. The group of bewildered patients parted, allowing the law enforcement officers to enter the clinic.

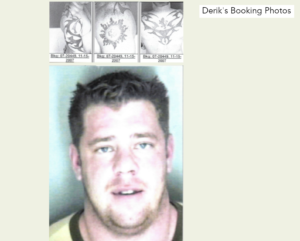

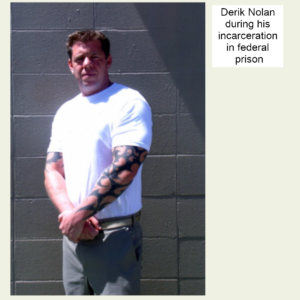

The agent found Derik Nolan standing at an administration desk with a cup of java. Thick black tribal tattoos encircled his left bicep and forearm. At six-foot tall and two hundred and ten-pounds of solid steroid enhanced muscle, he was an intimidating figure. Comfortable in his indifference, Derik’s perpetual smirk lets everyone know he thinks life’s a joke.

Not again, he thought, as the female agent stomped into the office. She thrust her DEA identification at several of the medical staff and another agent started barking orders. The clinic had been operating on the fringe of legality since its inception. Derik wondered if this would be the day they would force the clinic to close.

Derik Nolan did not own American Pain. What U.S. prosecutors would ultimately dub the single largest organized chain of pill mills in history. Distributing in excess of twenty-one million oxycodone within a two year period while raking in over $40 million in cash. However, Derik had built, organized and helped run the clinic from day one; an operation which Chris George, the owner, acknowledged skirted the edge of the law, but did not break it. Derik, however, had his doubts.

Over the next six hours, the DEA agents and assorted law enforcement reviewed patient files and inventoried the pharmacy’s drugs. They even threatened some of the doctors and seized several thousand oxycodone, but didn’t arrest anyone or shut the clinic down.

At 2:00 p.m., Derik stepped outside the office where over thirty patients were milling around the entrance, hoping, the clinic would reopen. With the agents, deputies and investigators packing documents and medication into their vehicles, Derik unabashedly yelled to the crowd, “Thanks for waiting everybody, we’re open for business, come on in!”

The tall, lean, black agent squeezed her eyelids into a leering glare. Derik gave her a wink and grinned.

DERIK NOLAN’S MUG SHOT rested just beneath Chris George’s, on the organizational chart mounted on the wall of the multi-organization taskforce’s office in West Palm Beach, Florida. The group itself was made up of DEA, ATF, FBI, Florida Department of Law Enforcement (FDLE) and multiple sheriff’s offices. It had been specifically organized to bring down American Pain. Underneath Derik’s photo was scribbled, “Enforcer.”

To this day, while sitting in a federal prison in Central Florida, Derik still doesn’t get it. He keeps telling me he’s a nice guy. He’s not a thug. He’s not what the government called American Pain’s, “muscle.”

“Do you see that?” asks Derik, in late 2016, during one of our preliminary conversations regarding my writing of his story. My eyes drift over the ink covering his arm and his broad, ridged, tension filled shoulders. His sharp, square jaw line and the scars on his knuckles.

“Nah,” I reply, insincerely, “I don’t see that at all.”

Derik looks like the kind of guy you’d like to have a couple beers with, however, you wouldn’t want to leave him alone with your wife or girlfriend. Not because you couldn’t trust Derik, but because you couldn’t trust her around him. He’s Tyler Durden, the anti-hero, from Fight Club.* A guys’ guy.

*Footnote:The character of Tyler Durden is played by Brad Pitt, in the 1999 movie Fight Club. Pitt portrays a young male, consumed with repressed rage, a disillusioned yuppie and malcontent. Tyler Durden establishes a fight club where the participants beat each other up and stage massive acts of sabotage to undermine the allure of consumerism.

“I’m not some kind a’ meathead, bro.”

“Right, you’re just like everybody else,” I chuckle. Mocking him just a little. “An average guy.”

Derik sighs, his eyes glaze over and drift off; and I know I’ve got him all wrong.

DERIK NOLAN’S MOTHER, Margaret, was lying naked on the couch in a post coital embrace with Bob Kelly—the man she’d been seeing. It was after midnight, September 12, 1981, and despite the darkness, Derik’s father, Robert, could see them clearly through the front window. The couple had been separated for several months. Both had been seeing other people, but they’d agreed to reconcile. His mother had said she was coming home. She’d promised. Yet, she was lying naked in another man’s arms. In another man’s home.

Derik’s father entered the house through the screen door at the side of the house with his sleepy four-year-old son shuffling in behind him. A little duckling in Superman Underoos, trying to rub sleep out of his eyes.

Although some of the details are cloudy, Derik distinctly recalls his mother gasping, “Oh shit” at the sight of her husband standing in the living room; and his father barking, “Oh shit’s right!” Bob jolted awake and all hell broke loose.

The two men fought, Robert, however, was a big man, a strong man, and Bob took a beating as Derik’s mother screamed. He was insane with anger and enraged. Suddenly, Derik’s father grabbed a knife out of the butcher block in the kitchen and Bob ran out of the house.

Robert caught up to him in the driveway. He plunged the knife into his wife’s lover—stabbing him 58 times, according to Derik, while his son cried and Derik’s mother begged, “Don’t kill ‘im, kill me! Kill me, it’s my fault!”

“Don’t worry bitch,” yelled Robert, hunched over Bob’s motionless body, “you’re next!”

Derik’s father murdered his mother in the kitchen of Bob’s house as his little boy watched. Decades later, Derik still remembers the linoleum floor, slick with blood and his mother’s lifeless stare. Standing in the passenger seat of his father’s truck as they drove away. The light in the window of the house fading into the distance.

Hours later, Robert Nolan turned himself in at the local police station.

“I remember wanting my mom,” recalls Derik. “I was only four, but I knew she was gone.” Derik talks about the murder with an odd detachment. While discussing the subject he has to pause several times to take deep cleansing breaths. He asks me how much longer do we have to talk about her? He doesn’t like to discuss the murder. He doesn’t want to think about her. He’s not the type of man who’s comfortable with his emotions. “I didn’t hate him for what he did,” confesses Derik. “He was my father. He just lost control and made a terrible mistake, but it doesn’t justify what he did.”

During his father’s trial, Derik lived with his Uncle Eric, his wife and cousins, Todd and Kim. After his father was found innocent, by reason of temporary insanity, Derik remained with his uncle. It was a more stable, safe environment.

His father married Kimberly Lewis shortly after the trial. Over the next several years the couple had three boys and eventually moved to New Jersey.

To hear Derik tell it, his teen years were unremarkable. However, he was the Jeffersonville Youngsville Central High School Trojan’s quarterback, but they never won Sectionals, Regionals or State. There were homecomings, proms and parties. Derik had lots of friends and girlfriends. He was an average teenage jock, according to Derik. Clean-cut. Polite. The kind of kid parents wanted their daughters to date.

He graduated in 1995 and moved to South Florida to attend West Palm Beach State College.

“By the time I was twenty I was working for a plumbing company, making seventy-five grand a year,” says Derik. He was managing millions in inventory and a dozen employees. Derik owned his own home and was driving a new Mustang. “I had a twenty-foot Wellcraft Eclipse, season tickets to the Dolphins. Everything a twenty-year-old could want…a really cool girlfriend and a gorgeous English bulldog I was totally in love with—”

I correct Derik, stating, “You mean you were in love with your gorgeous girlfriend.”

“No,” he snickers, “I meant the dog.”

DERIK’S FATHER came down to see his son in early January 1998. His second marriage was deteriorating. Kimberly had threatened to take the boys and move out of their house. Despite his domestic problems, Derik’s father seemed to be in good spirits. He wanted to spend a few days with his oldest son. To make things right, he told Derik. They had dinner a couple of times; he and his father spent a day fishing, but he never did clarify as to what the visit was about.

Derik recalls just before he flew back to New Jersey, his father gave him a big bear-hug and told Derik he loved him. Everything seemed fine.

Later that day, January 8, after Robert got home from the airport, his wife, Kimberly, handed him divorce papers. Derik’s father stepped into his study and snatched his shotgun out of the cabinet—a 20 gage Camper Special that Derik had bought him for Christmas. He entered the master bedroom and shot his second wife in the back as she turned to run. Kimberly crawled into the walk-in-closet. Robert reloaded the weapon and shot her a second time. This time in the head—a neighbor heard the shots and called 911.

Derik’s father then walked out to the cabana near the pool, made himself a drink and sat in a lounge chair at the edge of the water. He drank his scotch and smoked several cigarettes as he waited for law enforcement to arrive. Shortly thereafter, the SWAT Team surrounded the house.

Obscured from their view, Robert watched the SWAT members slowly tighten the perimeter around the house. He then placed a .25 Beretta pistol to his head and squeezed the trigger. The round entered the right-side of his temple, tore through his cerebellum and exited the left-side of his forehead, but it didn’t kill him. Derik’s father had to fire the semi-automatic a second time to finish the job.

“THEIR BODIES weren’t even cold before the reporters started calling,” Derik tells me. He flew to New Jersey and cleaned up the murder suicide scene. “I had to tell my little brothers what had happened… They were four, six and seven-years-old. Hardest fuckin’ thing I’ve ever had to do. No one should have to hear that.”

For the better part of a decade Derik worked on and off in the construction field while struggling. Not financially, but in the general progression of life. He did not finish college as he’d intended. He didn’t marry and have children. Instead, Derik jumped from relationship to relationship, never building up enough trust to commit to more than living with someone.

Although Derik may disagree, his choice of friends left something to be desired. Mostly, he bounced around with frat boy pranksters. The type of guys that get into bar fights. Adult males that play with firecrackers and sling-shots.

THE INSTANT he saw the North Port Police Department cruiser pull in behind his Jeep Grand Cherokee, Derik knew he was going to jail, again. It was November 15, 2007, and he wasn’t supposed to be driving.

Derik’s license had been suspended over a year earlier for neglecting to pay a driving without wearing a seatbelt ticket. He’d been ticketed for driving on a suspended license in August 2006 by the St. Lucie County Sheriff’s Office. Then again on December 3, 2006. Only that time he was arrested, spent the night in jail and had his Jeep impounded. He bonded out the next morning and picked up his vehicle from the impound lot. The following day, Derik was on his way to the DMV to pay his tickets and get his license re-instated, when he was pulled over for the third time by a St. Lucie County Sheriff’s cruiser for driving on a suspended license and rearrested. The next morning he bonded out, again.

The series of misdemeanor driving on a suspended license violations led to a five year suspension of his license and one year felony probation. So, on November 15, 2007, when the North Port Police officer told him to “please step out of the vehicle” Derik knew what time it was.

He quickly bonded out, called his probation officer and explained the arrest for driving on a suspended license. “Again?” she squawked. “Well, I’m gonna have to violate you—issue a warrant.”

“Nah,” he replied, “you don’t have to do that.”

“Yes I do Derik.” She told him the paperwork would take at least two weeks. “I’ll let you know when you’ve gotta turn yourself in. Whatever you do, don’t drive anymore.”

On Tuesday, November 22, 2007, a week after that call, a West Palm Beach County Sheriff’s cruiser pulled in behind Derik’s Jeep and hit the lights. This time however, after Derik bonded out, the sheriff’s office refused to release his vehicle. It had been used to commit a felony—driving on a suspended license—and thereby subject to seizure.

“MAYBE YOU shouldn’t mention all the driving on a suspended stuff,” suggests Derik. He tilts his head back slightly, doing his best high-school-bully imitation. “They make me sound a little irresponsible. I mean, I did have a guy that drove me around most a’ the time… He didn’t show up a couple a’ times, and that’s how the whole thing got outta hand.”

I told him I was putting it in. “It’s funny.”

“It’s not funny bro, they sold my fuckin’ jeep at auction and I ended up havin’ to do six weeks in jail (for the probation violation). It sucked!”

OXYCODONE, the drug has been around since the 1920’s, and has been reasonably prescribed for decades with no adverse effects to our national addiction to opioids. The problem started in 1996, when a struggling Purdue Pharma introduced OxyContin—containing a 12-hour controlled release oxycodone formula—and their marketing department kicked into high gear. One tablet, twice a day, provided “smooth and sustained pain control” was their pitch. However, the drug wore off after only 8-hours.

Purdue pumped tens of millions of dollars into advertising, expanded their sales force and pitched their product by incorrectly listing OxyContin as a moderate-potent opioid that could be prescribed with relative safety to patients with limited addiction or overdose potential.

When the patients complained the drug wore off hours before their next scheduled treatment, doctors were instructed to increase the dosage—larger milligrams meant more profits.

Over the next decade—directly following Purdue’s marketing campaign—three things happened in the United States: one, Purdue’s profits shot up from $400 million to over $3 billion annually; two, oxycodone prescriptions—across the board increased substantially; and three, opioid addiction in the United States increased ten fold. It was pure corporate greed.

Even when the DEA eventually indicted Purdue’s top executives for “mislabeling” the drug—putting a stop to their campaign of addiction—the executives only got probation. By then the damage was done, an epidemic had been created.

DERIK STEPPED OUT of the St. Lucie County Jail on January 22, 2008, a twenty-nine-year-old felon—now serving two years probation in West Palm Beach County and Sarasota County—with no job and nowhere to live, and he still didn’t have a driver’s license. He ended up moving into a shitty little two-bedroom apartment in West Palm Beach with a guy he’d known from high school.

Derik’s buddy Chris George called a couple weeks later. He’d met Chris, and his twin brother Jeff, years earlier while building new homes during the housing boom. They were a couple of rich beef-cake pretty-boys whose father owned Majestic Homes; Derik had done some subcontract work for him and the trio became friends. They were all into steroids and strippers; the twins were even more reckless and immature than Derik. The fact is, Derik liked the Georges a lot, particularly Chris. They got along real well.

Chris needed Derik to help him do a “quickie build out” for the pain clinic he was opening.

“You’re not a doctor,” laughed Derik. “What’re you talkin’ about?”

“You don’t have to be a doctor to own a clinic.” Believe it or not most hospitals and clinics are not owned by medical professionals. The only requirement was an occupational license and proper zoning.

The doctors who work for pain clinics primarily help patients manage their pain by proscribing some form of oxycodone, a semi-synthetic opioid. It’s available as Roxicodone for breakthrough pain and in a controlled release form, known as OxyContin.

Despite needing to be under a physician’s care to obtain a prescription for the highly additive narcotic, “roxies” and “oxies” were becoming the street drug of choice in Central Florida and in a dozen other southern states.

“That doesn’t sound right, doesn’t sound legal.”

“It’s legal.”

Chris already owned a couple youth rejuvenation clinics with a quack doctor named Michael Overstreet. Steroid clinic. So, Derik thought, It might be possible. It might be legal.

The office building was located in Oakland Park, about thirty miles south of West Palm Beach. A low budget commercial space in a lower middleclass area. There was no shortage of laundromats, pawn shops or vagrants. It took less than a week to gut the interior and do a cheap renovation. No permits or inspections. The large red and white sign, South Florida Pain Clinic, required more paperwork than licensing the clinic itself. According to Derik, they never were able to get the permits for the sign. They just put it up.

Within days of the paint drying, the clinic was open for business and seeing patients. Just over a week later, Derik was still trying to wrap his head around how Chris could open a pain clinic. He and his roommate were headed home from a construction job when his cell rang. Chris needs him to baby-sit the clinic the following day. Dianna—Chris’ ex-stripper girlfriend—the office manager, didn’t feel comfortable with the clientele. Overstreet was typically in the examination room and she was alone most of the day in the receptionist area with the patients.

“Some a’ these guys are sketchy,” said Chris. South Florida Pain was advertising in the back of the New Times, a local paper that advertised escorts and massage parlors. Plus, the clinic wasn’t requiring MRI’s. As a result, South Florida Pain was attracting patients exhibiting drug seeking behavior. Opiate addicts. Junkies. “I’ll give you four hundred bucks for the day.”

“Dude, I don’t know,” sighed Derik. The whole place felt illegal. “You’re gonna get me locked up.”

Chris threw in a gym membership and Derik agreed. It was just one day. That one day turned into two days a week. Then Dianna asked Derik to come to work fulltime.

“I’ll pay you whatever you want,” she said. “I’ll pick you up every morning and drop you off.”

That’s how Derik Nolan got involved in the pain clinic business, as a favor for a friend.

DR. OVERSTREET DIDN’T SHOW up Monday morning after his weeklong fishing trip to Panama. No one knew where he was or how to get hold of him. An Indian woman, Dr. Rachel Gittens had filled in for Overstreet, but she’d returned to New York and there were no other doctors at the clinic. Patients were sitting in the waiting room rocking and perspiring or wandering around the parking lot, periodically throwing-up in garbage cans due to withdrawals. Derik told Chris that Overstreet was a flake. He’d never liked him. He probably wasn’t coming back.

In a panic, Chris called Gittens and convinced her to fly back to Florida and take over for Overstreet. She hopped on the next plane to South Florida and was seeing patients that afternoon.

Not long after, they learned that Overstreet had flipped his Jeep while on vacation. He ended up dying in a shallow ditch somewhere in Panama. He wasn’t coming back.

Chris placed an ad on Craigslist for a doctor. Days later he received a call from Dr. Enock Joseph, a 39-year-old gynecologist who was working at Pain Be Gone. He was making $35 a patient. Chris offered him $75 and Joseph started within the week.

South Florida Pain now had two doctors cranking out scripts from 8:00 a.m. till 10:00 p.m. seeing ten to twelve patients per hour. Each receiving roughly 240 oxycodone and 120 controlled-release oxycodone. However, Chris kept the Craigslist ad running. Within weeks, he’d hired Dr. Patrick Graham and Dr. Eddie Sollie. Then there was Dr. Arcatis, Dr. Rolfe, Dr. Silk, etc. Most worked part-time. They’d come in for a couple hours and leave with a grand or two.

Derik could only remember one doctor who refused to work for the clinic; the interview had gone fine, but when the doctor got home that night, he ran a background search on Chris and came across several arrests. The next morning he called Chris and told him he couldn’t work for him.

The business model wasn’t all that sophisticated. An initial consultation ran $200, each subsequent visit cost $150. The patients then had the option to fill their scripts at the clinic or at a local pharmacy. South Florida Pain quickly became a mill, churning out opiates and raking in lots and lots of cash.

“THIS CAN’T BE LEGAL,” Derik told Chris, while cutting through a filet at Rain Dancer Steak House. It was nearly 11:00 p.m., sometime in early May 2008. Everyday they were seeing more and more patients. The clinic had been open over two months and Derik couldn’t believe some government organization hadn’t shut them down, yet.

“Alcohol’s legal and you don’t need a script,” mumbled Chris. “California’s got medical marijuana… ” According to Chris, if the doctors felt the patients were in need of medication, they wrote them a prescription. No one was guaranteed medication. Neither Chris, Derik or Dianna were doctors, all they were doing was running the clinic. “If any laws are being broken, it’s by the doctors.”

“Sure,” grunted Derik, unconvinced, “sounds good.” However, Derik knew Chris was specifically ordering generic versions of Roxicodone and OxyContin from multiple wholesalers using each doctors DEA registration number, in an attempt not to raise any red flags. His concern being the ever-increasing amount of oxycodone being purchased would put South Florida Pain on someone’s radar.

The clinic was bringing in $50,000 a day, roughly a million dollars a month and Chris knew that was only a fraction of its potential. Derik figured he’d stick around until he got his driver’s license back or the authorities chained the doors closed—whichever came first—but then he was gone.

“Don’t start talkin’ about leaving again,” said Chris. “Dianna and the docs like having you there. ” Everyone felt safer when Derik was around. “You know what we’re dealing with.”

Zombies, is what Derik called them. Opioid dependent patients with sluggish response time and endlessly sleepy, dazed expressionless faces. There were some patients with a legitimate need for controlling pain. Individuals with verifiable medical issues like cancer, bulging disks, etc. Derik always made sure those patients were seen first. There was no reason for them to be subjected to the zombies, so, he always got them in and out of the clinic as soon as possible.

Unfortunately, the bulk of South Florida Pain’s clientele were straight junkies. They’d “nod out” while sitting in the waiting room or wander around the parking lot smoking cigarettes. Or worse, they would sit in their vehicles, crush up pills and snort them while sitting in front of the clinic.

Like toddlers in a daycare, every 15 minutes or so, Derik had to go outside and herd the zombies back into the waiting room before the neighbors complained. It was hardly a business-like, clinical environment.

BY THE TIME DR. GITTENS mentioned that the clinic needed to start requiring diagnostic work—like drug tests and MRI’s—Chris and Derik were acutely aware that opioids were becoming a national problem. However, pain clinics, not the pharmaceutical companies nor the junkies, were being blamed. So they decided to tighten-up on the clinic’s prescription

requirements.

MRI’s required a doctor’s referral, so Derik had Gittens and several of the doctors sign blank prescriptions. He then turned around and charged the patients fifty bucks for the referrals—Derik wrote 40 the first day.

A week later MRI sales people began showing up. Reps from Plantation MRI, Faye Imaging, Delray Diagnostics, Commercial MRI, etc. College educated medical industry professionals, were suddenly kissing Chris and Derik’s asses. Requesting lunch appointments, where they’d pitch their companies’ services and offer them NASCAR, Dolphins and Miami Heat tickets and gift certificates for anywhere they wanted. But the real incentive for Chris and Derik wasn’t the kickbacks, it was turnaround—the industry average is 72 hours.

“Bro,” Chris told one rep, “we’re gonna need ’em way faster than that.”

“Yeah dude,” interjected Derik. “The amount a’ patients we’re gonna be sending you…three days ain’t gonna cut it.” It was the equivalent of Beavis and Butthead negotiating with Dr. Sanjay Gupta. “And with cash incentive.”

“Right, right, bro, enough with the fuckin’ gift cards.”

The clinic was referring so many patients, the MRI companies began competing with one another for the clinics business. Within the first month, several of them dropped their turn around time from 72 hours to 48 hours. Then 24 hours. On Fridays the reps would meet Derik in the parking lot to drop off thousands of dollars in cash kickbacks.

THE BILLBOARDS read PAIN CLINIC, along with the clinic’s phone and highway exit number. Chris lined Interstate-95 with them and they worked. The clinic had been advertising in the New Times and a dozen different yellow pages ads, additionally, they were using search engine optimization—you couldn’t type “pain clinic” without being directed to the clinic’s site—but the billboards really brought in the business. Business from South Florida and beyond. Before long “pillbillies” from the hills of Alabama, Georgia, Tennessee, etc. descended on the clinic.

Suddenly, the parking lot was overflowing with vehicles with out-of-state-tags. That was a problem. Within weeks there were too many vehicles for the parking lot and too many patients for the waiting room. They wore wifebeaters and spat chew while standing in line outside the clinic, and eventually the neighbors started complaining.

Before long the South Florida Sun-Sentinel ran the article Neighbors Calling Clinic A Pain. Patients were parking in their business’ parking lots and using their restrooms. Reeking havoc, shoplifting, dining and dashing; pulling what Derik dubbed, “junkie stunts.” Then the Oakland Park Police Department began harassing South Florida Pain’s customers. They’d pull over patients as they left the clinic, search their vehicles and question them regarding their prescriptions. Sometimes the cops would arrest them and tow their vehicles.

Chris and Derik got the message.

“THE COPS WERE AN ISSUE,” says Derik. By August 2008, the clinic had relocated to an office complex located two miles west of I-95. There was plenty of square footage and parking spaces. “It was just a temporary space until the unit we wanted became available.” Derik laughs, “We threw it together, like a triage center.” They stapled panel-board walls up and divided the space into small exam rooms along with a large waiting area.

Within days South Florida Pain begin receiving complaints from the neighboring businesses. The zombies were urinating in their business’ bushes and behind their customers’ cars. According to Derik, they were pulling junkie stunts. Several had been seen tossing trash in the parking lot and getting blowjobs in their vehicles.

“We hadn’t been open two fuckin’ weeks when this insurance guy comes in,” recalls Derik. “He tells me ‘Your patients keep coming in my business (his Allstate agency) like they’re gonna buy an auto policy or home owners insurance. Then they ask to use the restroom’.” Most of the time, the patients would use the facilities and walk out without buying anything. However, multiple patients had passed out on the toilet after shooting-up. He told Derik he was constantly finding needles in the trash or floating in the toilet bowl.

Derik asked the agent what he expected him to do about it. The guy started yelling and “I had to toss ‘im outta the fuckin’ place,” says Derik. “I’m pretty sure that’s the guy that called Carmel Cafiero, the reporter with (WSVNTV) Channel Seven News.”

Cafiero specialized in tabloid sensational investigative journalism. On October 17, she ambushed Derik and Chris outside South Florida Pain’s triage center. Her cameraman sidestepped around them as the reporter thrust her microphone into their faces and asked about patients snorting pills and shooting-up. She wanted to know why so many of their patients were from out-of-state.

Chris and Derik ducked into the clinic, leaving the reporter outside. She spent the next few hours accosting patients and shouting questions at the doctors, but no one had a comment. Overall, Cafiero didn’t get much out of the ambush. However, when the report ran later that week, it painted a sinister picture of South Florida Pain, along with Chris and Derik.

CASH WAS COMING in so quickly they began stuffing it into black Hefty garbage-bags. Once each bag was full, Derik would take them in the back and Chris would pile the bills into the cash counter machines. The bundles were then wrapped and stacked into cardboard I-Cup (instant drug test kit) boxes for transport to the bank.

Chris’ bank was initially apprehensive about accepting deposits of $50,000 to $100,000 in cash from a medical clinic dispensing narcotics. But when he began walking in with $200,000 to $300,000 their trepidation turned to fear and the bank closed Chris’ business account.

“What kind a’ bank won’t take cash?” Chris used to complain. They tried several other banks, but they continued to get the same story. “It’s suspicious,” the bank managers would tell them. “Legitimate businesses don’t deal strictly in cash.”

One bank after another allowed them to open business accounts, only to close them days later. Chris had boxes of cash stashed around his house. Two hundred thousand dollars here and half a million dollars there.

The cash was a real problem. Especially, for Jeff George’s roommate, John Robert Eddy. He had what Derik describes as “sticky fingers.”

A SINGLE BEAD OF SWEAT slowly rolled down Robby’s forehead as the polygraph examiner methodically asked his questions. His monotone voice gave no indication of whether the machine was accepting Robby’s answers as deceptive or truthful.

Three hundred grand had been stolen out of Chris’ vehicle a month earlier and two days prior, over $200,000 had gotten snatched during a burglary of Chris’ house. Chris and his brother, Jeff George, had narrowed the suspects down to three of their friends: Chris Hudson, Gino Marquez and John “Robby” Eddy.

Derik glared at Robby, from the doorway of Chris George’s dinning room. He had instructions not to let anyone leave until the tests were finished. Derik could see the perspiration seeping into his cotton-t, turning the material dark underneath Robby’s armpits. He’d never particularly liked Robby or the other two. They were your basic scumbags, according to Derik. Leeches, always looking for a hand out.

Once the last of them had been tested, Chris talked to the examiner. Then Chris stepped into the living room and announced all three of them had passed.

The suspects feigned disgust at having been accused of such a thing. They were all friends “for god’s sake!” After they’d stomped out, Chris informed Derik, Robby had failed miserably.

Days later, Jeff kept Robby busy at lunch while Derik searched his vehicle. He found $20,000 in cash stuffed in a bag in a toolbox, wrapped in the clinic’s rubber bands. That really pissed Derik off. Admittedly, he went a little nuts at the thought of a supposed friend stealing from his friends.

Derik and Chris waited in Jeff’s massive house for Jeff and Robby to return. They were concealed in a room adjacent to the master bedroom when Jeff and Robby entered the room. Robby barely had enough time to register Derik’s presence before Derik hit him with a right hook. Smash! Robby fell backward, hit the wall, simultaneously, lost control of his bowels and bladder, Derik scooped him up and slammed him onto the carpet. Boom!

As Derik snapped the handcuffs on Robby, he realized he had shit smeared on his arm. The stench was unmistakable. He stepped into the restroom to wash himself off. Robby regained consciousness and, according to FBI reports, Chris and Jeff started demanding the money. Suddenly, Jeff pulled out a semi-automatic and fired several shots into the floor next to Robby’s head.

Derik ran out of the bathroom, the stench of feces and urine was overwhelming and he damn near puked. Chris and Jeff where standing over Robby, all they wanted was the money back, they told him, as Robby screamed, “I don’t have it!”

Derik popped Robby a few times while yelling at him to “give up the money!” He scared him pretty good, but Robby didn’t change his story. He confessed to the $20,000 Derik had found, however, he wouldn’t admit to the theft of the $300,000 or the two hundred plus grand. Robby began sobbing and pleading for them to let him go. Suddenly, Chris and Jeff weren’t so sure he was the perpetrator.

The George brothers decided to just let Robby go; he didn’t have the cash or (even if he did) he wasn’t going to admit it. No harm no foul. The problem was Robby wasn’t the kind of guy to keep his mouth shut.

“What’re you two talkin’ ’bout?” asked Derik. “We’re not lettin’ him go.” They had brought him to Jeff’s house, handcuffed him and tried to beat a confession out of him. “That’s kidnapping. You can get twenty-to-thirty years for kidnapping. We gotta kill ‘im.”

“No!” yelled both Chris and Jeff.

The George’s owned an expansive swampy wooded area—roughly 20 miles from Jeff’s house—where the three friends hunted occasionally. “We’ll bury ‘im in the swamp, no one’ll miss him. He’s an asshole.”

Robby pleaded with them to let him go. He swore he wouldn’t say anything. Chris and Jeff believed him. They ended up having him sign some paperwork, exonerating the three of them of the incident and they gave him $10,000 in hush money. Derik still isn’t sure if he’d have killed Robby.

He was just about as pissed off at Chris and Jeff. They were constantly getting him involved in their bullshit.

Several months later Robby had a domestic violence incident involving his girlfriend. He was arrested for being a felon in possession of a firearm by the Palm Beach County Sheriff’s Office; according to the FBI 302 report of Robby’s interview, in an effort to get a reduced sentence, he immediately spilled his guts about the kidnapping and the pain clinics. He described the Georges’ pain clinics as a criminal enterprise and Derik as their cokehead

thug enforcer.

That’s how Derik’s name came to the attention of the FBI, and not long afterward, the DEA started paying attention too.

DERIK WAS STANDING at a desk in the back office, sipping a coffee, when a tall, lean black woman walked into the administrative area. It was mid November 2008, slightly before 8:00 a.m. She held up a set of credentials that read DEA and Derik’s stomach wrenched. Another agent barked for the staff to produce their ID’s.

Over the next six hours the DEA agents, and assorted law enforcement, reviewed patient files and inventoried the pharmacy’s drugs. They even threatened some of the doctors, but they didn’t arrest anyone. They seized several thousand oxycodone, but they didn’t shut the clinic down.

Once they left, Chris and Derik stepped into Chris’ office. Derik tilted his head back and asked, “What do we do, bro? We got patients standing outside and the docs are in the (employee) lounge, doin’ nothing.”

Chris glanced apprehensively at the stacks of patient files—files the DEA had gone through—and he let out a deep breath. “I think… I know the files are good—MRI’s, UAL (Urinalysis Labs). They’re all there, so we’re good,” he said, more to himself than to Derik. “We’re good. We’re good.”

“Alright, bro,” grunted Derik and he headed to the entrance.

At 2:00 p.m., Derik stepped outside, where over thirty patients were lingering around the parking lot. With the agents and the investigators packing seized documents and medication into their vehicles, Derik yelled to the crowd, “Thanks for waiting everybody. We’re open for business, come on in!”

The tall, lean black agent squeezed her eyelids into a leering glare and Derik gave her a wink and a grin.

Within a week of the DEA leaving, the office complex’s management company told Chris and Derik the clinic had to vacate the premises. Leave. Get out. There were zombies roaming the parking lot and the complex’s other tenants were complaining. There was a constant stream of inquires by news organizations and law enforcement agencies.

“We’ve got undercover police vans in the parking lot,” whined the property manager. The semi-raid probably didn’t help. “You guys have to go.”

Chris and Derik quickly moved the clinic to a large space in an industrial area near the airport. They weren’t there a month before the zombies began wreaking havoc and they were forced to leave. That particular eviction, according to Derik, was orchestrated by the local sheriff in collusion with the county zoning department.

BY THE TIME the clinic relocated to Boca Raton in March 2009, they’d changed the clinic’s name to American Pain—to avoid the bad press—and hired several new doctors; one being Dr. Cynthia Cadet, a thin, black woman in her mid-thirties with what Derik described as, a hot body and bookish sex appeal.

Over the course of several months, he began paying attention to Cadet. She was nice. Too nice to be working at the clinic, around all the junkies, thought Derik. He started to worry about her. Derik began walking Cadet to her car at night and picking her up lunch during the day—so she didn’t have to see the insanity in the waiting room—and he’d check on her when her examinations ran too long.

Derik liked Cadet a lot. They had an odd, beauty and the beast, friendship—the bookish female doctor and the tattooed thuggish head of security. In truth, Derik had a little crush on Cadet, but he never acted on it for several reasons: one, she was married—although she admitted it was an unhappy marriage—and two, Derik felt like she could do better than him. He wanted better for her than him.

Over the course of the next several months, Chris and Derik transformed American Pain into the largest pain clinic in the nation; treating over 250 clients per day with a base of over 20,000 patients. They were churning out over 30,000 oxycodone per day and raking in more cash than they could spend.

Chris’ twin-brother, Jeff, was running two clinics in West Palm Beach and Chris’ girlfriend, Dianna, managed a third clinic across town. In addition to American Pain’s in-house pharmacy, Chris had bought a freestanding pharmacy and within months a third pharmacy.

There were local, state and federal agencies actively trying to shut them down and they were constantly being inspected or probed. But no one seemed to be able to figure out how to close their doors.

The patients—opioid addicts from all over the country were taking Interstate-95, what law enforcement dubbed “The Oxy Express,” to South Florida—they kept coming and coming. The volume was overwhelming.

For the sake of efficiency, the entire operation was McDonalized. Derik hired a bunch of silicon-breasted-exstrippers and steroided-out-gym-rats to work as: security guards, receptionists, medical staff and quality control personnel. An assembly-line of staff filled out the clinic’s medical forms, verified all referrals, medical records and MRI’s. From the outside, the clinic’s staff had the air of legitimacy, but just underneath their casual business attire, were belly-button-rings and tattoos.

Cash was stuffed into garbage cans and counted by Chris or the office manager.

For the first time, Derik believed he and Chris had stumbled into a legal loophole. They were drug dealers, but semi-legit drug dealers; and it didn’t matter to them that the DEA had formed a taskforce and had a surveillance van parked in the clinic’s lot.

Sure, thought Derik, we’re coloring outside the lines a little bit, but Chris’ business model is bullet proof. “Everything we were doing was legal,” says Derik. He and Chris were working 60 to 70 hours a week. “We couldn’t even spend all the cash.” They were driving Lamborghinis, BMW’s, Land Rovers and Mercedes; “and I didn’t even have a fuckin’ license.”

Derik managed to get away from the clinic every once in awhile, he did a week in Florence, Italy, for an exgirlfriend’s wedding. There were a dozen long weekend trips to Las Vegas and New York, filled with strip clubs and gambling. He and Jeff partied with the bunnies at the Playboy mansion in LA.

“I’m not a flashy guy,” says Derik. “I had a bunch of designer stuff: Hugo Boss, Prada, Armani, but mostly…I’m a blue jeans and a t-shirt guy.”

AMERICAN PAIN was a circus. Derik was always trying to keep the zombies occupied. He made sure the clinic was visited regularly by food trucks—hotdog trucks, Italian icy trucks, ice-cream trucks, you name it. He’d have pizza delivered. There were always movies playing on the flat screens in the waiting room. Regardless, he and the clinic’s security guards still had to do sweeps of the parking lot; where they were forever catching patients pulling junkie stunts like, throwing-up, snorting pills or having sex.

Once, Dr. Cadet called Derik in the staff lounge. She and another doctor had noticed brown spots on several of their patients’ faces. Possibly bruises or smudges of dirt.

“Have you noticed that?” asked Cadet.

“I haven’t, but I’ll look into it doc.”

The clinic was churning out over two dozen patients an hour at this point and Derik hardly paid them any attention. He stepped into the waiting room and began scanning its occupants. There were over one hundred slack-jawed zombies aimlessly wandering about or mindlessly slouching in chairs, staring into space, sipping sodas and eating ice-cream cones.

Derik noticed one particular patient balancing a chocolate ice-cream cone while struggling to keep his eyes open. Slowly the zombie’s eyelids grew heavier and heavier until they closed. His head slowly began to drop forward until his chin dipped into the chocolate scoop. Immediately the patient jolted upright, but he didn’t seem to notice the smudge of chocolate on his chin.

Derik glanced around and noticed several other patients with spots on their noses, checks and foreheads. This is insanity, he thought. God damn junkies.

American Pain’s addicts were more of a problem than ever by the summer of 2009. While sitting in the waiting room, patients would pop Xanax to calm their nerves and curb their withdrawals. At least once a week some junky would go into a dementia-induced-hallucination and start swatting at nonexistent butterflies or strip off their clothes and have an argument with some imaginary tormentor. Then they’d drop onto the floor, go into a seizure and the staff would have to call an ambulance.

Not a day went by that Derik or one of the staff didn’t catch some patient lying on their paperwork. They were constantly catching doctor shoppers—patients acquiring oxycodone from multiple doctors—or trying to pass-off a forged MRI. Sometimes, Derik would physically escort them to the door and eject them from the premises. Other times he would take pity on them and point them toward the Interstate.

By this point Faye Imaging had purchased a mobile MRI machine and they were spitting out MRI’s within an hour. The truck was permanently parked in the parking lot behind Solid Gold, a strip club off Blue Heron Blvd. and I-95.

Often, the addict would confide in him. “There’s nothing actually wrong with me.”

Derik would suggest they tape a staple to their lower-back. The metal will typically warp the MRI’s resolution, thereby creating the illusion of an abnormality.

“You sure that’ll work?”

“Yeah,” he’d reply with a grin. “Of course, depending on the strength of the MRI’s magnet, it might rip the staple through your spine. But I’m willing to bet your life it’ll be fine.”

“Thanks, Derik,” they’d say, and stumble off to the strip club.

To keep the zombies from wreaking havoc, Derik typically gave them a speech twice a day. He would stomp into the waiting room, act frustrated, run his hand through his hair and demand everyone’s attention. “Here’s the deal,” he’d announce, “if you’ve got out-of-state-tags on your vehicle, don’t park in the clinic’s lot. Don’t drive under the influence of the meds—if you do, and you get arrested, don’t call here and ask me to bail you out. Don’t give me a fake MRI—if you do, I’ll take your consultation fee and kick you out, and I’m gonna keep your money—and whatever you do, don’t let me catch you selling pills.”

The speeches were legendary. Constantly evolving. Designed to keep everyone in-line, but it didn’t deter the hardcore junkies. Nothing could.

THE CLINIC’S pharmacy tech was Derik’s oasis in the sea of filth and insanity in which he dealt with daily. Jennifer was a petite bottle-blond hottie with a tight little ass, according to Derik, and a great smile. She was shiny and new. Innocent. A single mother, with a precocious little toddler daughter, that Derik was in love with. Jennifer was everything Derik wanted, for all of about…15 minutes.

Shortly after they moved in together her trailer park trash roots began to show. Jennifer quit working at the clinic, and suddenly she started making demands.

“Jennifer didn’t even have a job,” recalls Derik, “but she wanted a maid to help clean the townhouse, and a daycare to watch her daughter.”

Jennifer had been with the clinic during the “surprise inspection!” and she’d seen the van sitting in the parking lot. During one particularly nasty argument she let Derik know it was in both his and Chris’ best interest to “keep her happy.”

“This chick was fuckin’ extorting me,” says Derik. “Jennifer would make these veiled threats and I’d start mentally digging a hole in the swamp, but Chris kept telling me to do whatever she said. ‘Just pay ‘er we’re makin’ millions,’ he’d say.” So Derik bought Jennifer a new car and jewelry, whatever she wanted. “Her daughter was adorable; she was one of those little kids that makes you wanna get married and be, you know, respectable… But the mother,” Derik slid his pointer finger across his neck in a cut throat motion, “she was the worst.”

IN DERIK’S OPINION everyone that worked at the clinic knew it was a pill mill. Even the doctors knew. How could they not know. But none of them ever verbalized it. None dared utter those words aloud.

Derik would joke with Dr. Cadet, saying, “You know we’re all drug dealers, right? This place is nothin’ but a dope hole.”

“No Derik,” she would reply with a disappointed smirk. “We’re helping these patients; they’re suffering. They’re in pain and they need treatment.”

Derik shrugged it off. The way he saw it, all the doctors were basing their participation in the clinic on plausible deniability. The only one who even hinted at what the clinic was, however, was Dr. Patrick Graham.

Periodically, Graham would refuse to write a patient a prescription and Derik would have to give him a “talking to.” Something Derik always found amusing.

Graham worked part-time, he’d come in two, sometimes three days a week for a couple hours. It was easy money, but the guy was always bitching and moaning. He’d complain that the patients had track-marks or they would specifically refer to oxycodone by its street names: “blues” and “greens.” Graham didn’t like that. “I know what’s going on here,” Graham once told Derik. “I know what this place is…”

“Yeah,” Derik replied arching his brow while nodding his understanding. Trying not to smile. Graham had been collecting two to three grand a week in cash for the past year. Of course he knew what the clinic was. “So, if you know what this place is doc, what’re we talkin’ about this for? (Derik pointed to the exam room) Get back in there and start writtin’ scripts.”

Graham acted appalled, as he moped around, put on a show of reluctance, and Derik suggested the doctor would “probably be happier working somewhere else.”

“Alright now, Derik,” Graham snapped. “That’s not necessary.” He grabbed the next patient’s chart and headed back to the exam room. They went through the same routine every week or two. Derik still doesn’t know why. Neither he nor Chris ever once forced a doctor to write a prescription. Not once.

CHRIS’ BROTHER’S CLINIC wasn’t doing anywhere near the patient volume of Chris and Derik’s American Pain; instead, Jeff was focusing on selling in bulk to oxycodone dealers. He would dummy-up the paperwork for several thousand pills and have Zack Boisett, a buddy fresh out of the Marines, delivering the oxies to dealers in the area.

Chris mentioned his little side endeavor to Derik on a couple occasions, but he wasn’t interested.

“Dude, there’s no reason to do that,” said Derik. “You’re turning a legitimate money making enterprise into something illegal; it’s stupid.”

THE ISSUE OCCURRED due to the multi-agency taskforce, which included the DEA and the FBI. They were constantly sending in undercover officers and CIs (Confidential Informants), posing as patients, in an effort to obtain information on the clinic’s activities and evidence the doctors were prescribing narcotics outside the realm of legitimate medical practices.

The CI’s would admit to excessive drinking or indicate they had pain in a region in contradiction to their MRI’s results; and the doctors would always refuse to write them a script. Its Derik’s understanding that out of half a dozen CI’s, none received a prescription, ever.

Regardless, on November 6, 2009, the taskforce agents were somehow able to obtain permission to wiretap Chris’ phone calls.

The government would ultimately allege that patients overdosed and people died as a direct result of the doctors at American Pain prescribing oxycodone. In reality, the government overreached in an effort to paint everyone involved with the clinic as a monster.

In fact, the government went to great lengths to connect those deaths with American Pain. For example, one patient death resulted from a documented heart condition, however, he had been a patient and did have oxycodone in his system. According to the government this somehow meant, he died because he was their patient. Another patent died in a car accident. He did have oxycodone in his system, but he had prescriptions from several other clinics—an obvious doctor shopper—and he had not been to American Pain in several months. There’s no way to know if the accident was a result of the oxycodone nor was there any way of knowing which of the multiple pain clinics’ doctors had prescribed it. Then there was Tracy Mason who overdosed behind the barn of his family’s farm. Tracy hadn’t received a prescription from American Pain in over six months, still, he had oxycodone in his system, so the government insisted his death was a result of him being a patient.

Unfortunately, there was a car accident on November 19, 2009, that was the subject of one of Chris and Derik’s conversations. Several patients of another clinic—patients that were obviously high on oxycodone—somehow managed to get themselves struck by a train.

“You gotta be an idiot to get hit by a train,” Chris said to Derik in a recorded call. “What idiots!”

“Yeah,” laughed Derik. “Who gets killed by a train?”

Those conversations, along with the CI’s—despite none of them ever receiving a prescription—helped to create the foundation of the government’s case against Chris, Jeff and Derik, among others; in what the government characterized as a continuing criminal enterprise run by racketeers.

DR. CADET WAS UPSET, Derik could tell. She’d been going through a divorce, they had two kids, and her soon-to-be ex-husband was making it hard on her. Derik didn’t like that.

“Look,” he said, glancing around in a conspiratorial way. He told Cadet he didn’t like seeing her unhappy. All she had to do was give him the word, “I’ll throw this guy in the trunk of my car and drop ‘im in a hole—I got the perfect spot.”

Cadet giggled. “No. That’s sweet, but it’ll work its self out.”

Derik shrugged and grunted, “I’ll dig a hole this weekend, just in case you change your mind.”

Cadet laughed. In her defense, she genuinely believed he was playing.

COMPETITION BEGAN ENCROACHING in what Chris and Derik considered their territory. Mostly, they were small mom and pop pain clinics, seeing less than 30 patients a day. They posed no significant threat to American Pain’s Super Walmart of Oxycodone. As long as the smaller clinics minded their own business Chris and Derik didn’t have a problem with them.

Unfortunately, in late November—within a span of a week—several patients approached Derik. All said they had received calls from him regarding American Pain’s newest clinic, Jacksonville Pain. Derik blew off the first few, thinking they were junkie delusions; there was no plan for a Jacksonville location and he damned sure hadn’t called any of them.

One patient however, provided Derik with a return number. He gave it a try, asked to speak with Derik Nolan and sure enough, the guy that answered replied, “This is Derik Nolan.” He then proceeded to tell Derik how the new American Pain location would save the average out-of-state patient 12 hours round trip drive time. Derik was furious.

“Listen up punk, I’m Derik Nolan,” he growled into the receiver. “You’re screwing with the wrong motherfucker. You call one more of our patients, I’m gonna put a hurtin’ on you.”

The following morning Derik and Chris made some inquiries regarding Jacksonville Pain; they quickly discovered that Pete with Faye Imaging—their go to guy for MRI’s—was acting as a front man for Zackary Rose an American Pain patient, and he had incorporated Jacksonville Pain. Between the two of them they were systematically calling all American Pain’s out-of-state clients and diverting them to Jacksonville Pain.

“It opens December thirteenth,” Chris told Derik. They weren’t sure what type of volume the Jacksonville clinic could handle, but once the zombies showed up with their cash—keep in mind eighty percent of all American Pain’s patients were from out of state—Chris and Derik knew Jacksonville Pain would make arrangements to accommodate them.

“What do you wanna do?” asked Derik; and this is where working within the grey area of the law turned into the darkness of night.

“Burn that fucker to the slab.”

“Consider it done.”

Derik grabbed a gas can and several flares, but before he got a chance to torch the competition, Chris pulled the plug. Instead, he had come across information verifying Rose was doctor shopping. So Chris decided they were going to drive up to Jacksonville on the clinic’s opening day, check out the operation and have a “sit down” with the owners, Pete and Rose. He planned on giving them an ultimatum: close up shop or hand over half your business—it was only fair, the majority of their business was based off the theft of American Pain’s patients.

Unfortunately, Derik’s eighteen-year-old brother, Kevin, who was on Christmas break visiting, and Derik—thinking there wouldn’t be any trouble—made the mistake of letting him tag along.

By the time Chris and Hudson, one of Chris’ scumbag buddies, showed up in the parking lot of Jacksonville Pain, Derik and Kevin had already determined that Faye Imaging was providing fake MRI’s in order for the Jacksonville clinic’s doctors to pump out oxycodone scripts. Jacksonville Pain was a pill mill with the capability of rapid expansion. Even more infuriating, Derik had recognized half a dozen of their patients.

Derik could see Chris was pissed when he entered the clinic to talk to Rose. Derik stepped into the clinic just as the meeting deteriorated into a serious confrontation. Suddenly, both Rose and some wannabe thug staffer, pulled out large caliber semi-autos and everyone started screaming at one another.

“You’d better be ready to use that,” snapped Derik at the staffer pointing the weapon, “cause if you’re not, I’m gonna beat you to death with it.”

The confrontation spilled outside and suddenly, multiple Duval County Sheriff’s cruisers whipped into the parking lot. The deputies immediately jumped on Derik, cuffed him and stuffed him in the back of a patrol vehicle. Within minutes, Chris, Hudson and Derik’s kid brother were in handcuffs.

The whole bunch was charged with extortion and thrown into the county jail. Chris’ girlfriend, Dianna hired some big-shot attorney. A couple days later they were released on bonds between $60,000 and $250,000, provided they wear ankle-monitors.

Within weeks of returning to South Florida, a second clinic, Palm Beach Pain, moved in right down the street. The owner hired a guy to wave a sign at oncoming traffic, directing American Pain’s customers to Palm Beach Pain’s clinic. No big deal, thought Derik. Next they hired someone to leave fliers on their customers’ vehicles. That was a little uncalled for, but not worthy of a reaction. Then, Derik found a stack of Palm Beach Pain’s business cards in American Pain’s waiting room, and he decided to set them straight.

Derik parked his Mercedes at the curb directly in front of Palm Beach Pain and stormed into their office. He threw the stack of cards in the owner’s face and spat, “You keep this shit up motherfucker, you’re gonna need pain management!” and he stomped out.

Hours later, American Pain’s security guard caught some guy passing out Palm Beach Pain fliers to patients as they exited the clinic. Derik mentioned it to Jeff and he growled, “This mean war; we need to teach these pricks a lesson.”

“Dude,” sighed Derik; he was still wearing his ankle-monitors and had pending charges in Jacksonville, “you’re gonna get me arrested again.”

“I’m not saying torch it, we’ll just send them a message… We’ll bring Zack.”

Derik looked at Jeff and for the first time he noticed the pattern; every time he or his brother had a problem, they expected Derik to solve it for them. Still, just after midnight, Derik, Jeff and Zack pulled up to Palm Beach Pain; Derik thought, This is not a good idea as he pulled out his sling-shot and a bag of ball-bearings.

He fired a dozen of the steel projectiles at the clinic; blowing out their sign and windows.

Months later the state of Florida dropped the charges against Chris, Hudson, Derik and his little brother Kevin.

ACCORDING TO CHRIS, American Pain’s new location—a nearly 30,000 sq ft three story building with 300 parking spaces—could handle the ballooning patient volume. However, according to Derik, within weeks of moving into the super sized clinic in January 2010, their staff of two dozen; meat-heads, ex-strippers and five fulltime doctors, were seeing a tsunami of over five hundred patients a day out of a revolving client base of 30,000 patients. They were prescribing so much oxycodone, the clinic couldn’t keep enough in stock to fill all the scripts. Derik and Chris were carrying out boxes full of cash and depositing it into multiple bank accounts, safety deposit boxes and several safes Chris had installed in his mother’s attic—and by the end of the month they’d outgrown the building.

In the two years Chris and Derik had run the clinics, they’d brought in over $40 million, and distributed in excess of twenty-one million units of oxycodone.

They were building out several thousand square feet of the clinic’s office space to house multiple MRI machines and scouting locations in nine different states for future American Pain clinics. In short, Derik told me they were “planning world domination of the pain industry.”

ON MARCH 3, 2010, hundreds of deputized taskforce law enforcement officers, simultaneously served search and seizure warrants on the American Pain organization. At 6:00 a.m., they began banging on the doors of every employee and doctors’ residence, while raiding American Pain, Executive Pain, East Coast Pain and Hallandale Pain.

Derik had just stepped out of the shower when Chris called. “There are FBI agents everywhere,” he yelled in a panic. “They’re raiding my house.”

“What’re you talkin’ about?”

“They’re everywhere. It’s over dude, it’s all over.”

The feds seized over $7 million from Chris, his vehicles and several shotguns and a semi-automatic handgun. No one was arrested, but they stripped the pain clinics of every patient file, computer and all medical equipment. They gutted the places like fish. However, not one taskforce agent showed up to Derik’s house. No one even called. Not that there was anything to seize. According to Derik, although he’d made millions during his tenure with American Pain, he insists he’d blown most of it on “booze, Benzs and bimbos.”

Not long after the raids, Derik’s girlfriend, Jennifer, called it quits. She packed herself, and her little girl up, and moved out. Derik says he only missed “the kid. She was a real cutie.”

Over the next several months most of the doctors agreed to cooperate with the government in exchange for reduced sentences; Dr. Cadet and Dr. Castronuovo, however, refused. Chris, Jeff and Derik, among others, vowed not to accept a plea. Not to cooperate against one anther. No fucking way I’m ratting out my friends, Derik told himself, over and over. Never.

Chris and Derik went so far as to get tattoos of rats dangling from nooses; and pledged death before dishonor.

During a get-together at Jeff’s house, in an effort to obtain further evidence of racketeering the FBI wired Zack; he’d been a scout sniper in the Marines, and “for thirty thousand cash,” he told Chris, Jeff and Derik, “I’ll pop a rock in Robby. I guarantee he never testifies.”

They joked about knocking off everyone who was cooperating with the government. However, when Zack began to push them Derik told him, “I ain’t doing that bro.”

Derik later found out that Robby’s father was a DEA agent, and he’d managed to keep his son from being indicted for conspiring to sell oxycodone—he’d been delivering pills for Jeff for over a year.

Then, on October 15, 2010, after trying unsuccessfully to obtain enough evidence to indict or convince Chris to cooperate, the federal prosecutor in charge, Assistant U.S. Attorney Paul Schwartz, had Chris arrested for being a felon in possession of a firearm—based on the weapons they’d seized during the raid on his house.

Still, Chris refused to accept a plea or cooperate; and their lawyers were insisting they could beat the case.

DERIK’S BREATH was creating circles of fog on the visitation room plexiglas separating him and Chris. He couldn’t believe what he was hearing. Everyone was cooperating, Chris, Jeff and Dianna, among others.

“That’s the way it is,” Chris said into the visitation phone’s receiver and he glanced away. He couldn’t look into Derik’s eyes as he told him “if you don’t take a plea we’re gonna testify against you—all of us. You’ll get a life sentence.” Chris told Derik if he took a plea he’d get ten or fifteen years, but if he cooperated he’d end up with five years.

Between December 2011 and February 2012, Chris was sentenced to seventeen and a half years; Jeff got fifteen and eight months; and Dianna received thirty months. The bulk of the doctors received between two years and seventy-eight months—which was later reduced by half for their cooperation.

Derik plead guilty to one count of racketeering and he was sentenced to fourteen years in federal prison.

Dr. Cynthia Cadet and Dr. Joseph Castronuovo were the only two “conspirators” to hold out. The government was furious. They immediately indicted the two doctors for distribution of narcotics outside the scope of legitimate medical purposes, which resulted in seven deaths. They were facing life sentences.

DURING THE SUMMER of 2013, Derik was called to testify at Drs. Cadet and Castronuovo’s trial. He didn’t want to be sitting in the witness box, but it was the only chance he had at getting his sentence reduced—half seemed to be the standard.

Initially, Derik’s testimony seemed beneficial to the government. He laid out the clinics’ roots for the jury as Cadet stared at him from the defense table. She looked sad, Derik recalls, and maybe a little disappointed.

When Assistant U.S. Attorney Schwartz asked Derik if the staff at the clinics had seen the insanity in the waiting room. The zombies reeking havoc. The junky stunts. Derik admitted they had. Everyone had. When the prosecutor asked if everyone had seen Derik manhandle unruly patients and give his infamous speeches, Derik replied, “Yeah man,” he extended his thick tattooed arms as far as the handcuffs would allow and said, “Look at me. I’m not a wolf in sheep’s clothing. I’m a wolf in wolf’s clothing; I don’t hide nothing from nobody.”

Slowly, throughout the course of the second day, Cadet’s sadness wore on him. She was facing a life sentence, and she’d been his friend. She didn’t deserve that.

When Assistant U.S. Attorney Schwartz asked if Derik had been promised anything in exchange for his testimony—a question he knew to answer in the negative—he replied, “Yeah.” He then pointed to the prosecutor with his chin and added, “You told me if I testified, you’d cut my sentence.”

It was tantamount to witness tampering and the prosecutor was furious.

During his cross-examination, Derik admitted that the American Pain clinics had looked legitimate. Hell, he’d thought they were legitimate. They had all the right licenses, paperwork and diagnostics. It was possible that Cadet could have been fooled by the veneer. As Derik testified, the color slowly began to drain from the prosecutor’s face; he could do nothing but scowl at Derik as his case against Cadet began to crumble with each of Derik’s statements.

“She’s an awesome person,” he told the jury. “She’s my friend. I don’t want to see anybody hurt.” Derik was obviously conflicted about his testimony. “I feel horrible.”

The following day, Schwartz hammered away at Derik in an attempt to mitigate the damage. “How did American Pain make its money?”

“Selling pills,” he replied. That had always been the plan. Derik admitted he was a drug dealer.

“Was Christopher George a drug dealer?”

“The biggest.”

“Did you ever sit down with any of the doctors, including defendant Cadet, and say, ‘We’re operating a pill mill’?”

Derik paused for a fraction of a second, he knew what the prosecutor wanted him to say. Instead, he glanced at Cadet and said, “No.”

The jury found Dr. Cynthia Cadet and Dr. Robert Castronuovo not guilty of distribution and the resulting deaths.

SITTING IN FEDERAL PRISON Derik looks lost. It’s early 2017, and he tells me—due to his unfavorable testimony and the acquittal of the doctors—the U.S. Attorney’s Office refused to reduce his sentence. He’s currently scheduled to be released in 2024. So I ask him why he didn’t just say she knew the place was a pill mill. It’s what the prosecutor wanted to hear. It would have changed everything for him.

“When you’re sitting up there,” replies Derik, he pauses and struggles for several seconds, searching for the right words and says, “you think you can do it. You think that you can sacrifice that person for yourself, but you can’t. I couldn’t.”

We sat there in silence, on the concrete benches outside the prison’s housing units, in the center of hundreds of inmates, underneath dozens of seagulls. Even in January the Florida sun is warm against our faces.

“So,” I ask, “Did she know?”

Derik cocks his head to the side and gives me an ambiguous grin. That was our last interview; and yeah, I had Derik all wrong