SATURDAY NIGHT AT THE ROUND UP, a pop-country dance club located just outside Tampa’s city limits. The place was packed with drunken southern belles line dancing to Blake Shelton’s Redneck Girl underneath the disco balls and duhalf naked strippers in Stetsons, seductively slow riding the mechanical bull. My high school buddies and I had been drinking rum and Coke and snorting oxys most of the night. I was 17-years-old and more than buzzed, dancing with a twentysomething, raven haired beauty, sporting a tramp stamp and silicone implants. That might have been the reason I didn’t notice the hulking bouncers pulling my friends off the dance floor, until one of the country boys tapped on my shoulder. “You!” yelled the bouncer over the music. “You’re outta here!”

I was escorted outside with my friends, where the man asked for my ID. I quickly produced 23-year-old Arnold James Reyes’ Florida Drivers License.

The bouncer’s eyes darted between my face and Reyes’. We were both thin and roughly five-foot-eight inches tall with dark spiked hair. But we weren’t twins. “Nah,” he grunted, “that’s not you.”

“You’re crazy,” I replied, as a Hillsborough County Sheriff’s cruiser pulled up to the honky-tonk’s entrance just behind me.

“We’ll see,” chuckled the bouncer, motioning to the deputy exiting the patrol vehicle.

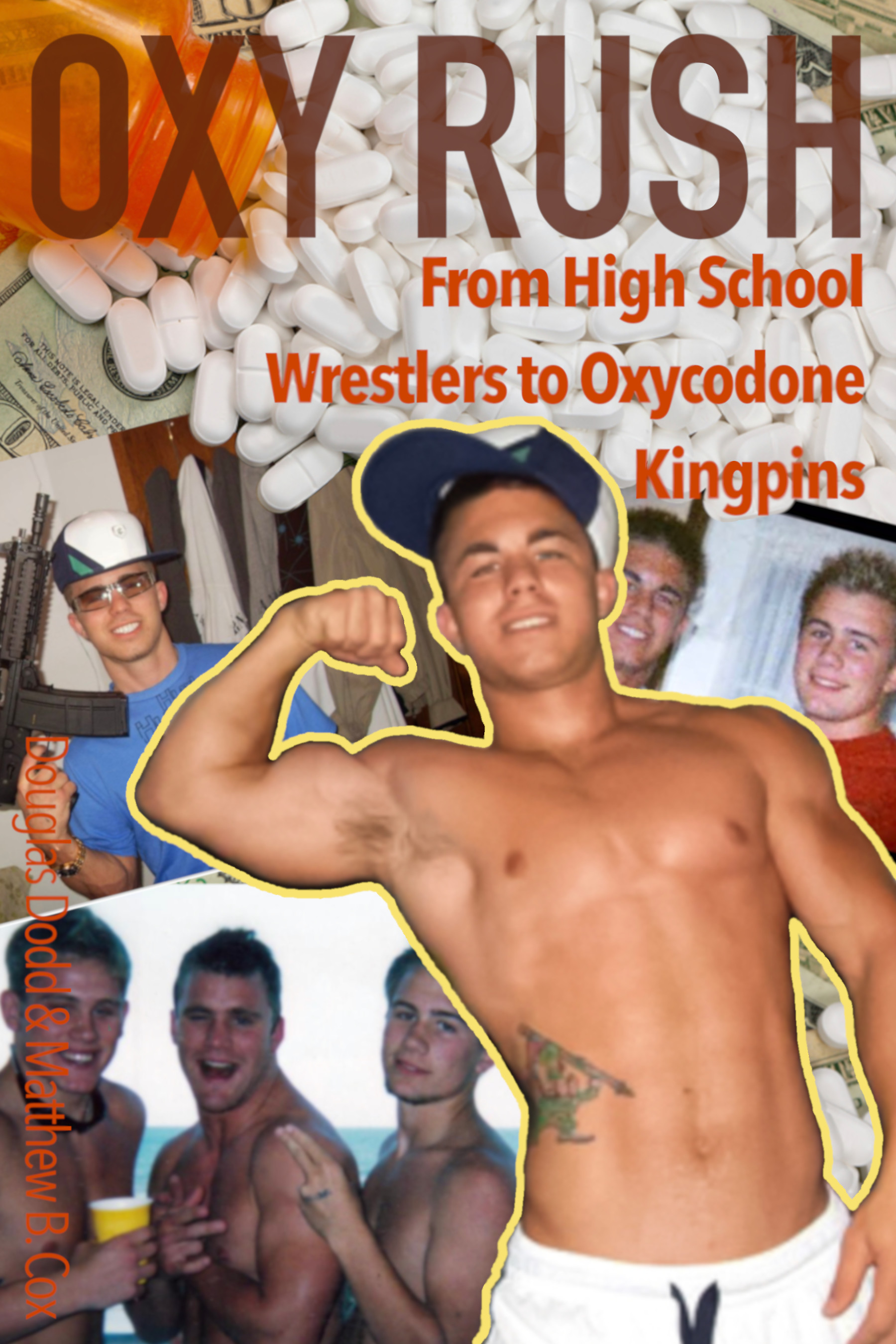

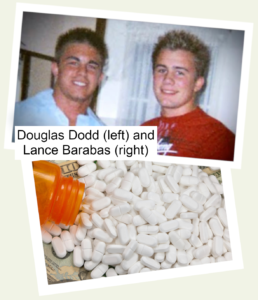

Between me, Douglas Dodd, my best friend Lance Barabas, his brothers, and our buddy Richard Sullivan, our group—which prosecutors would ultimately dub “the Barabas criminal enterprise”—were making millions shipping hundreds of thousands of oxycodone pills throughout the country. What prosecutors would eventually call one of the largest suppliers of the ever increasing oxycodone epidemic; and I had roughly 100 of the powerful painkillers tucked away in a metal vial hanging from the chain around my neck, just beneath my shirt—a 15 year minimum mandatory sentence in the state of Florida.

“Shit,” I hissed. I slowly glanced toward the massive bouncers flanking my left and to the deputy closing in on my right.

“Don’t even think about it,” growled the officer; my adrenaline spiked and my fight or flight instinct kicked in. I bolted past my friends and across the parking lot, shot into four lanes of traffic on Hillsborough Avenue, causing nearly a dozen vehicles to swerve and lockup their brakes. I could hear screeching tires, crunching steel, and cracking tail lights, but I didn’t look back. I just kept running. I raced behind a building, yanked off my necklace, and stashed it in a tree. My heart was pounding adrenaline through my veins as I scaled the chain link fence of a flea market and hid in a maze of rusted out storage units.

Within minutes, the deputy found my vial of oxycodone hanging from the tree branch—more than enough for a trafficking charge. “I’m gonna need backup,” he said into his shoulder-radio “a couple’a dogs and a helicopter too.” The sheriff’s K-9 unit showed up within five minutes and tracked my scent to the flea market.

I’d just caught my breath when I heard the German Shepherds barking and saw the blue lights of several cruisers at the entrance of the open air market. I jumped the fence and crawled through a muddy field as the sheriff’s deputies surrounded the area and swarmed inside. That’s when I heard the helicopter and saw its spotlight sweeping toward me. Drenched in mud and sweat, I quickly got to my feet, ran into a nearby plaza where over a dozen tractor trailers were parked. I crawled underneath one and laid between its massive tires. I called Lance, and told him where I was as the beam of the helicopter’s spotlight passed over the trailer. “Bro,” I whispered, as two deputies walked by, haphazardly shining their MagLites underneath the trailers, “you’ve gotta come get me.”

“Sit tight,” said Lance, one of his brothers and a friend had been arrested. Another buddy had wrecked Lance’s Dodge truck and our remaining friends were screaming at one another. “But we’re coming to get you.” He ended the call and told everyone they needed to pick me up immediately. Most of them wanted to get out of the area before they were arrested for trespassing or underage drinking. “Well, we’re not leaving him!”

At roughly the same time, several deputies spotted Lance on the side of the highway. Due to our similarity, they encircled him with their patrol vehicles, jumped out of the cruisers, and drew their weapons. “Get on the ground!” they yelled. “Get on the ground!”

Lance dropped to his belly as multiple K-9 unit officers approached the area with German Shepherds. A portly deputy jammed his knee into Lance’s back and slapped a pair of cuffs on his wrist. “What were you doing in the flea market?” barked one of the K-9 unit officers, while two of the dogs growled and snapped their razor teeth inches from his face. Lance could feel the dog’s breath and saliva on his cheek.

“I wasn’t at the flea market!” replied Lance. “I’ve been here—”

“What’re you doing with all them pills!?” snapped the deputy, as he yanked Lance off the asphalt. But Lance didn’t respond. “Boy, you’re fucking with the wrong officer!” Then he shoved him in the back of the cruiser.

I’d been waiting over an hour, dry heaving and sweating in the frigid night air, when two patrol vehicles pulled into the plaza and parked. So I headed for a 7-Eleven and called Lance’s cell. “Who am I speaking with?” asked an official voice.

“Doug,” I replied. “Where’s Lance?”

“I’ve got ‘im in the back of my patrol car. But I need to release him to someone. Where are you at?”

“Sir, I’m only seventeen-years-old . . . how’re you gonna release him to me?”

“Listen kid,” growled the officer, “if you don’t tell me where you’re at, I’m gonna book your little pal here! What do you have to say to that, smart ass?”

“Tell Lance I love ‘im,” I chuckled, “and I’ll bail him out in the morning.” I disconnected and walked into the convenience store, covered in dirt and grass, and grabbed a soda out of the beverage cooler. The clerk gawked at me as I tossed some cash on the counter and exited the store. It was after two o’clock in the morning when I called my cousin and said, “Come get me. They arrested Lance.” Then I popped the top and gulped down my icy cool, liquid Orange Crush.

IN 1994, I WAS JUST A SKINNY, five-years-old dirty-footed kid, running around the trailer parks of New Port Richey, Florida, when my mother—a waitress—caught my father nailing another waitress—my future stepmother—in the back seat of the family Pontiac Trans Am. Between my father’s affinity for waitresses and my mother’s addiction to Budweiser, their marriage was doomed.

My father was awarded custody during the week and my mother got me on the weekends. Over the next several years my mother went through a couple of alcoholic husbands and a dozen domestic violence reports. Lots of bruises and restraining orders.

By the time I was 14-years-old, Sherry—my current step mother—caught my father sleeping with yet another waitress—my new future stepmother—and she moved out. My father divorced Sherry and married the newest waitress—Holly—and they decided to move to upstate New York and start a business. But all my friends and family were in Florida and I didn’t want to go. My mother had just kicked out my latest stepfather, and she wanted me to stay with her. Seemed like a good idea at the time. But it didn’t take long before cracks started to appear. After a couple of beers, my mother became a pretty mean drunk; she’d start complaining about my curfew, my chores, and my music—typical teenager, parent stuff. The truth is she just liked to get drunk and argue.

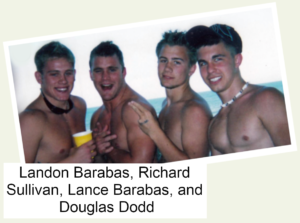

I STARTED HUDSON HIGH SCHOOL in 2003; it was mostly populated by lower middle class kids, driving dated pickup trucks and muscle cars. There were lots of rednecks, jocks and cheerleaders. I met Lance and Landon Barabas the first day of wrestling practice, with their buddy Richard Sullivan. They were a bunch of blond haired, blue-eyed, wise cracking, rich kids surrounded by poor white trash. Despite our economic differences, we hit it off right away. We started hanging out after school and car-pooling to wrestling practices.

The first time Landon picked me up, he showed up in a brand new fully loaded Ford Excursion on 20 inch rims—he was 16-years-old! Landon said we had to stop by their house and pick-up something. A couple minutes later, he pulled the Ford up to Holy Ground; a homeless shelter with multiple commercial buildings and a Church. There were two dozen vagrants in tattered clothes hanging around the facility’s entrance.

“You live here?” I asked.

“Yeah, our mom owns it,” laughed Lance. “But we don’t live in the shelter.”

Miss Barabas was what I’d call “redneck rich.” Her boys all drove expensive vehicles, wore designer clothes, and had plenty of money, but lived in a doublewide trailer behind the facility.

WE SMOKED WEED BETWEEN CLASSES, wrestled during the week and partied on the weekends. We were inseparable, but there was one huge difference between us. They were rich kids and I was barely getting by.

Lance, the “Little General” was a control freak. Since the age of ten, he’d been running around his mother’s shelter, telling grown men to make their beds in the morning, and screaming, “Bed time!” at night. Then he’d flip off all the TV’s and lights. I loved him like a brother, but he was an Alpha male, gun nut with a big mouth and a Napoleon complex.

Lance’s brother Landon was a “Pretty Boy” that thrived on attention, and was so in love with himself he couldn’t pass a reflective surface without looking in it. He’d have carried around a compact if we’d have let him get away with it. Then there was Larry, the oldest of the Barabas brothers, he was a 400 pound “Lineman” that had blown off a full scholarship to FSU to stay close to his family and his high school sweetheart.

Our buddy Richard’s goal—in preparation for his future career as a porn star—was to fuck as many chicks at Hudson High as possible; he’d contracted multiple STD’s and been dubbed “Dirty Dick” by Lance, Landon, Larry, and me.

Despite our flaws, we were a tight group of friends. But I always felt like the odd man out. Their families owned restaurants and bars, assisted living facilities and homeless shelters. They had all the options in the world, and I was struggling to survive. While they were tag teaming cheerleaders and driving brand new trucks, I was working 40 hours a week as a fry cook at Mike’s Dockside, a sea food restaurant. I needed money to sign up for the wrestling team and to buy the necessary equipment, like shoes and head gear. I couldn’t ask my mother because she’d already told me, “The only thing I’m required to do is keep a roof over your head and food in the fridge . . . you wanna wrestle, you can pay for it yourself.”

But once I started receiving paychecks, my mother started demanding money for the utilities. “Isn’t that part of keeping a roof over my head?”

I started selling weed on the side to buy school supplies, clothes, and eventually my own car—a $3,500 Honda Prelude.

BY 2006, MY LIFE HAD BECOME one long rock video. I was acing my classes and kicking ass at wrestling meets during the week. And partying like a rock star with Lance and the guys every weekend. We’d all meet up at Arnold and John Reyes’ doublewide—along with around 100 other Hudson High students. The Reyes brother’s acre sized lot would be packed, bumper to bumper, with pickup trucks and muscle cars.

We’d move all the living room furniture outside and have wrestling matches with 60 kids drunk on hunch punch and Jell-O shots, crammed into the trailer cheering us on. It was a bunch of sweaty, southern boys pulling double leg take downs and hip tosses on one another; then body slamming each other on to the carpet and wrestling until someone ended up in a headlock or a rear naked choke, forcing them to tap out. It was more like a scene from Fight Club than your typical high school party. There was always a couple of fights and a lot of drinking.

You could usually find two or three drunken cheerleaders making out in a bedroom somewhere and a dozen jocks guzzling down Solo cups full of beer. Sometimes the crowd would swell to over 200 students dancing around bonfires and in the back of pickup trucks. The cops didn’t usually show up until after midnight. Those parties were the stuff of legends.

AROUND TEN O’CLOCK on February 10, 2006, I was driving home, smoking a joint, when a Florida State Trooper noticed I didn’t have my lights on. The trooper pulled behind the Honda and flashed his blue and whites. My heart was pounding as I nervously tossed the joint out the window and pulled to the curb.

The trooper said he smelled marijuana, which gave him probable cause to search the vehicle. He found a Ziploc bag with half an ounce—a misdemeanor—and arrested me.

The juvenile court judge ended up imposing a 2:30 p.m. curfew, three months of drug counseling, and nine months of probation.

Despite my mother’s multiple DUI’s, she was furious about the arrest. “How stupid can you be?” she said over and over. “You’re going to end up in fucking prison, you little…idiot!” And my favorite, “Sometimes I wish I’d never had you!” It got so bad, I eventually had to move in with my grandmother.

AS A RESULT OF MY CURFEW, I ended up hanging out with my cousin John, who lived down the street from my grandmother’s house. We spent our time watching movies and getting fucked up on oxycodone pain pills; a semi-synthetic opioid used for managing severe acute or chronic pain. It’s available as Roxicodone for breakthrough pain and in a controlled-release form, known as OxyContin. Unlike marijuana, opiates are out of your system within a couple of days. Quick and easy.

I knew a couple dozen people that took Roxicodone 30 milligram and OxyContin 20, 40, and 80 milligrams on a regular basis. In 2006, “roxies” and “oxys” were becoming the drug of choice in central Florida. From high school students to business professionals, everyone was taking them. My cousin hooked me up with a guy that had a couple of scripts. I bought 100 Roxicodone 30 mil’s for $8 per pill, hoping to sell them for $12 per pill over the next few weeks. Three days later they were gone. It was too easy. The whole thing came together real quick after that.

My buddy Anthony connected me with a married couple that had prescriptions. Another friend, Emanuel, got me another prescription. Plus Mitch, a guy I’d met at the drug treatment center, knew a couple guys with prescriptions, and Andrew, another friend, had four prescriptions from four different doctors. My cousin Russ gave me a bunch more guys with scripts. Within a few weeks I had over two thousand pills coming in per month. I started selling them for $15 per roxie or ten-packs for $120. I made almost ten grand my first month.

AROUND THE SAME TIME, things started to take off for me, in June of 2006, Lance “The Little General” and “Dirty Dick” Richard graduated Hudson High. Lance got a wrestling scholarship to Cumberland University in Knoxville, Tennessee—the same University where his older brother Landon the “Pretty Boy” was wrestling. But Lance was so love sick over his high school girlfriend, that within three months he dropped out of Cumberland and moved back to Florida.

Richard—whose parents could have easily paid for him to go to any University—moved to Los Angeles, California, to pursue his dream of being an adult film star. He thought it was going to be all tits and ass. Richard ended up going on several “interviews” with low level adult film directors and producers. During one interview, a supposed director tossed Richard some KY Jelly and told him he needed to video Richard masturbating “in order to gauge your girth and the consistency of your ejaculation.”

A month later, the video showed up on a gay porn site, collegehunksUSA.com, under the title “Derrick.” Richard called Lance from LA and asked him to pull up the website. Richard was posed naked, cock in hand, jacking it for the camera. “Be honest dude, how bad is it?”

“It’s bad Derrick… it’s bad.” With some help from Lance and me, it didn’t take long before the website went viral among the student body of Hudson High. When Richard moved back to Florida, we fucked with him mercilessly; telling him he didn’t measure up to porn work. These were the type of guys I was dealing with—love sick maniacs and sexual deviants.

IN JUNE OF 2007, I GRADUATED with honors and received the Principal’s Scholarship. My dad, several cousins, and my grandmothers were there among the sea of proud parents and friends. I remember looking out at the crowd, as I waited in line, and thinking maybe I’d see my mom, but she wasn’t there. I’m not sure why I thought she’d be at my graduation; she had never come to any of my wrestling matches. I did see Lance and the guys. They were laughing and waving as I walked across the stage, fucked up on roxies.

Shortly after I graduated, Lance and I enrolled full-time at Pasco Hernando Community College; taking business management courses. I’d gotten off probation, bought a Jeep Grand Cherokee and had plenty of money. Life was sweet.

A couple of months later, “Pretty Boy” Landon came down for summer break. He, Lance, and I were at Clearwater Beach; playing volleyball, listening to music and doing pills. “You know,” said Landon, as I handed him a couple roxies, “these things are going for almost a dollar a milligram in Tennessee.” Lance and I locked eyes for a split second, while Landon popped the pills into his mouth.

“You think you could sell some of ’em,” asked Lance.

“Fuck yeah, my buddy Justin will get rid of ’em.”

I fronted Landon 200 Roxicodone 30 milligrams just before he left for Knoxville. A couple days later, Lance told me his brother had sold the roxies for almost $4,000 and he needed more.

Lance and I bought several Muscle & Fitness magazines, a half dozen protein bars, and a couple vitamin bottles; then carefully peeled off the vitamin bottles’ seals, dumped out the contents, stuffed 500 oxycodone into the bottles, and re-glued the seals. I wrote a letter from Landon’s mom to her son; telling him how much she loved him and missed him—stuff my mom would never say—and we overnighted the package to Landon’s Cumberland University P.O. Box, via FedEx. The next day Landon got the pills and he sold them for almost ten grand.

Landon then went to Toys ‘R’ Us, bought a Teddy Bear, gutted it, stuffed the bear with our cash and overnighted it to his brother. We tracked the shipments all the way to the door—it was that easy. A week later, Landon needed 1,000, then it was 2,000. Then he asked for 3,000 pills and, at the time, I couldn’t get that many. So we went to a friend of Lance’s.

Nicolas Carter’s mother was a deputy sheriff, his uncle was an FBI agent and Nick was a known drug dealer. His toys filled up his entire yard. Nick had a Corvette, a 30 foot power boat, a Nissan Titan truck and plenty of money. Everything Lance and I wanted. He started selling us two thousand roxie 30s a week, for $10 per pill. Which wasn’t cheap, but we needed the pills. Between Florida and Tennessee, we were easily clearing over $40,000 a month—that’s a lot of Teddy Bears.

MY PLAN WAS TO SAVE HALF a million dollars by the time I got my BA, and quit. But Lance wanted more than that. He wanted a finely tuned organization of opiate distributors throughout the country. He wanted to be the next American Gangster. Scarface. The Lance Barabas Criminal Enterprise.

“PRETTY BOY” LANDON had put together a network of Cumberland wrestlers and college students in Knoxville to distribute the oxycodone to local dealers and he was ordering more pills every week. We were buying scripts from friends of friends, but it wasn’t enough. We started “sponsoring” people. My cousin Russ, Andrew, and Brian were constantly looking for people with back problems. We’d pay for their MRI’s, their doctor’s appointments at the pill mills and then we’d buy their prescriptions.

A couple months later, Landon came back to Florida with Danny and another guy from the Cumberland wrestling team—dealing pills for him in Tennessee. That night we all partied at Parana, a trendy four level, multi-bar dance club in Ybor City, near downtown Tampa. The place was jumping with wall to wall, heroin chic, wannabe models and college girls hustling drinks out of metro-sexual corporate lawyers and stock brokers. Everyone was dancing to Rick Ross’ This Is The Life and Drake singing Money To Blow—having a blast.

Over drinks, Danny suggested that he had people in Alaska that could easily move 10,000 Roxicodone or OxyContin per month. “And the prices are way higher than Tennessee,” he said. “Oxy eighties go for a hundred per pill.”

Danny’s guys in Anchorage flew into Tampa around a week later. We set up some anonymous Gmail accounts and bought a couple prepaid cells to use for business. Lance overnighted them 500 oxycodone the first week, then a 1,000 and then 2,000.

BETWEEN, ALASKA, FLORIDA, and Tennessee, we were making so much money, Lance “The Little General” transferred to Hillsborough Community College and leased a half million dollar place in Victory Lofts—a luxury high-rise in the Channelside district in downtown Tampa. Right next to Raheem Morris, the head coach of the Tampa Bay Buccaneers football team. It had ultra-modern stainless steel appliances, polished concrete floors and scored block walls. He blew a ton of money on furniture, electronics and parties.

When I first saw the loft, Lance and I stepped out onto the balcony, overlooking the Port Authority and the city of Tampa. “What do you think?” he asked, ecstatic with his trendy new loft.

He was hooked on opiates and throwing around money. “I think you’re gonna get us caught,” I replied, as I looked out at the dark choppy water of Tampa Bay.

“You’re overreacting,” he scoffed. “Everything’s fine.”

SOMETIME IN NOVEMBER OF 2007, the DEA suspended Cardinal Health’s controlled substance license, at its Lakeland distribution center, for illegally selling large amounts of oxycodone and hydrocodone to several Internet pharmacies. The problem was Cardinal’s distribution center serviced over 2,500 pharmacies in Florida, Georgia, and South Carolina; causing an immediate shortage of opiates. Pharmacies stopped accepting insurance and started hoarding the painkillers for their cash customers. The cost of roxies shot up from $.70 to around $3.50, and oxys jumped from $10.50 to roughly $12.50. The availability slowed down to a trickle and the street value doubled.

Nick’s inexhaustible supply was cut in half; Landon was screaming for more pills in Tennessee and Danny’s guys needed them in Alaska. We were regularly picking up a dozen customers’ prescriptions from multiple pharmacies on a weekly basis, but it wasn’t enough to meet the demand.

Lance was barking at everyone and flashing his Glock .45 every chance he got. At one point a sponsor was running late for work and couldn’t make a drop of roughly 500 oxycodone. Lance got on the phone with the guy and told him, “If you don’t get me those pills, I’m going to drive down to your job and put a bullet in your fucking head—got it?!”

When I heard about it, I called him up and said, “What the fuck’er you doing Lance, do you want to get arrested?!”

“I’m sorry bro, I just got in my feelings . . . we need the pills!”

We were getting calls from pharmacists saying, they’d hold our oxycodones, but we had to pay cash. The DEA suspension slowed us down, but it also increased our profit margin.

Eventually Cardinal paid a $34 million fine to settle the DEA charges. The flood gates were opened back up and the opiates poured back into the pharmacies. But no one at Cardinal went to prison. Drug dealing CEO’s don’t get prison sentences, they get fined.

A COUPLE MONTHS LATER—in mid-January of 2008—we spent the day partying at the Gasparilla parade in Ybor City. Then we hit the Round Up, just outside Tampa’s city limits. I got in without a problem, using Arnold’s ID, but Lance and “Pretty Boy” Landon, had to share Landon’s driver’s license. I hadn’t been in the club 30 minutes before Lance got caught trying to get in using his older brother’s ID. That’s when the bouncer tapped me on the shoulder and barked, “You! You’re outta here!”

A minute later I was running through traffic with 100 oxys hanging around my neck and a dozen deputies on my trail; jumping fences and hiding from helicopters. Twenty minutes after that, the sheriff’s mistakenly arrested Lance thinking he was me. They released him an hour later and apologized for the misunderstanding. “Next time,” warned the deputy, “keep some ID on you.”

My cousin Russ picked me up at a 7-Eleven around three o’clock in the morning.

ABOUT A WEEK LATER, UPS “LOST” two shipments of 1,500 pills on their way to Tennessee and Alaska. The truth is, the Pasco County Sheriff’s Department had seized the shipment, but due to Lance’s alias, they couldn’t track the package back to him. Instead, the manager of the UPS store contacted Lance on his prepaid cell and told him they’d located the packages, but he needed Lance to stop by to sign something before they could re-ship them.

When we pulled into the parking lot I spotted a black Ford Expedition with tinted windows and two clean-cut, law enforcement types sitting inside.

“Stop!” I snapped, and Lance pulled into a parking space. We both scanned the lot for additional officers while Lance mocked me for being “overly cautious.” Then he noticed two undercover narcotics officers sitting in a dark grey sedan, watching the entrance to the UPS store—three spaces away—and the color drained from Lance’s face.

Our hearts were thumping away as Lance called the UPS manager and told him, “I know the cops are trying to set me up . . . put ’em on the phone.” The manager didn’t even deny it, he just said, “Call back in five minutes.”

Seconds later—three spaces down—one of the undercover officers received a call on his cell and exited the sedan. When he stepped into the UPS store Lance turned to me and laughed, “That was close.” He was completely unconcerned about it.

That night Lance and Richard went out and bought these specially designed Pringles potato chip cans with hidden compartments in the bottom. They stuffed them full of several thousand oxycodone, bought some real Twinkies and Orange Crushes, and threw the grocery bag full of snacks into the trunk of Richard’s new limited edition Chip Foose Ford Mustang 5.0.

Richard started making a trip a week to Tennessee, until Lance decided to start shipping again. Nothing deterred him. By this point, Lance was buying more scripts than I was, and the money was really starting to come in. We had Wave Runners, four-wheelers, dirt-bikes and new trucks.

AROUND THE SAME TIME, I stopped by my maternal grandmother’s house one Saturday for a family holiday dinner and my mother was there. We hadn’t spoken in months and I had no plans to. I was driving my new Jeep Grand Cherokee and dressed in Affliction and Ralph Lauren. I was about half way to the front door when my mom rushed out of the house with a glass of wine in her hand and her arms outstretched. “How’s my baby boy doing?” She hugged me, looked me up and down, glanced at my Jeep, and said, “You’re doing so good Dougie. I’m proud of you.”

“You’re kidding right?” I’d wrestled all conference and finished one match from states, graduated with honors and she’d never said one word of encouragement. But now she was proud. There was no way my mother didn’t know how I was making my money. It’s not like I had a nine to five. I spent most of my time studying and picking up prescriptions. “You’re a real piece of work,” I said, “you know that?”

ON MAY 5, 2008, a girlfriend and I were smoking a blunt on our way to the beach, when we passed a Pinellas Sheriff’s cruiser. We got pulled over and searched.

The deputy found some marijuana in my pocket and around ten Roxicodone and two Xanax in a metal pill vial underneath my driver’s seat. He let my girlfriend go and arrested me.

I was brought downtown to a grungy interview room with the deputy and an undercover narcotics office. “That’s two felonies,” said the narcotics officer, pointing at two evidence bags of pills, lying on the table. “You haven’t been booked yet, so there’s still time to help yourself. Here’s what you’re gonna do; you’re going to bring me to your dealer, introduce me to ‘im and vouch for me—”

“What’re you talking about, those aren’t even my pills!”

“Well,” he growled and slid the bag toward me, “we’ve got you for ’em. That’s five years. Or you can cooperate…”

I thought about my network of high school friends and grinned. “Book me.”

After I was photographed and printed, I called Lance and explained the situation. “Should I call your mom?” laughed Lance.

“Don’t fuck around, bro! I need you to bond me out—it’s ten grand.” By that night Lance had paid my bond and had me back on the street.

The following day, I hired an attorney who told me I was looking at three to five years in a Florida state prison. “They don’t have air conditioning in state prison,” she said. “You’re not going to like it.” I told the lawyer that the pills weren’t mine and she grinned skeptically. “Can you prove that?”

I knew Andrew had a prescription specifically for Roxicodone and Xanax. “Definitely.”

That night I had Andrew write an affidavit stating, he had accidentally left his pill vial in my vehicle. I then made copies of Andrew’s prescriptions, and my lawyer forwarded everything to the prosecutor’s office. When I asked Andrew to do it . . . he didn’t even hesitate.

Two weeks before my trial, the state dropped everything except the marijuana charge, which was only a misdemeanor. I got nine months probation.

AFTER MY NEAR MISS, Lance and I decided we needed to get our own prescriptions. So we went to Nick. He had his own script, but nothing was wrong with him. He coached us on what to do to get an MRI; explained how to arch and twist our backs, to put pressure on our spine, which created bulging of the discs. The position was extremely painful over the prolonged period of time we had to lie in the MRI machine. The radiologist tech kept saying, “I know you’re in pain, but you’ve gotta stop moving.”

Both our MRI’s showed identical disc bulges with bilateral mild to moderate neural forminal narrowing of L-3, L-4, and L5-S1; in addition to space narrowing at L5-S1. We went to Detox & Pain Management Clinic, run by Dr. Richard Keesal; this frail junkie doctor in his late 60’s. The guy looked like a heroin addict—track marks on his arms and everything. He did a cursory examination and wrote us prescriptions for 240 roxie 30s and 120 oxy 40s. Those pills were worth over ten grand a month.

Lance turned around and sent Richard to get his MRI. Then Larry, Justin, and a dozen other co-conspirators.

By this point we were buying and shipping roughly 20,000 Roxicodone and OxyContin throughout the country every month. We were hooked on our own product and making bad decisions. Lance “The Little General” walked into a dealership and paid for a supercharged Ford F-150 Lightning with cash. He peeled off something like twenty-five grand in 50’s and 100’s—that’s the kind of stupid shit that gets you looked at by the feds.

At night, Lance would sit on his balcony with his AR-15 assault rifle and target people on the street with his laser sight knowing he had $35,000 in cash and 1,000 pills in his dresser. That’s tantamount to driving around in a stolen car with a broken tail light and a body in the trunk—pure stupidity.

AROUND THAT TIME, I stopped by Lance’s place and walked in on him with a mutual friend—Joe Hankinson—from high school using an automatic money counter to tally up a couple hundred thousand dollars of drug proceeds. There were gutted Teddy Bear carcasses, cotton-stuffed animal guts, and stacks of cash strewn across the kitchen table. Lance’s .308 Remington sniper rifle was sitting on a bipod at their feet and a Glock .45 lying on the corner of the table—it was a scene straight out of Scarface.

“What the fuck are you doing?!” I screamed.

Joe wasn’t a part of our organization and shouldn’t have been privy to what we were into, and Lance knew it. “You’re paranoid!” snapped Lance. “He’s alright.”

“I’m telling you, you’re gonna get us busted.”

NOTHING SEEMED TO SLOW LANCE DOWN. When his girlfriend got busted with over 400 oxycodone and charged with trafficking—a 25 year minimum mandatory sentence in the state of Florida—Lance got her a lawyer that beat the charge and had her record expunged.

When I broke this guy’s jaw, fighting over some girl, and he went to the police; Lance went behind my back, went to the guy’s house, and told him, “If you don’t drop the fucking charges on Doug, you’re going to have a problem with me and my whole organization . . .” Then he pulled up the front of his shirt so the guy could see the Glock tucked into the holster strapped to his belt. “That’s a problem you don’t want.”

The guy was so scared he dropped the charges the following morning.

BY EARLY DECEMBER OF 2008—despite the fact that “Pretty Boy” Landon was distributing in excess of 10,000 pills per month in Tennessee—he was so strung out on opiates, Landon somehow managed to run out of oxycodone for himself. He called his kid brother in a panic. “Lance, you’ve gotta overnight me some pills today, or I’m gonna get sick.” Lance FedEx’ed 400 painkillers to Landon’s Cumberland University P.O. Box.

The following day—on December 8—Landon picked up the package around 10:30 a.m. As he was exiting the post office unscrewing the vitamin bottle’s lid, four black sedans converged on him in the parking lot. They screeched to a stop and half a dozen Lebanon Police Department undercover narcotics officers swarmed out of the vehicles with weapons drawn. “Down on the ground!” they screamed. “Down on the ground!”

Landon dropped the pills and hit the pavement. His adrenaline was pumping away as the police cuffed his hands behind his back as he lay face down on the asphalt in a puddle of Roxicodone. Landon was so strung out; he shot his tongue out like a gecko, slurping up several pills before the officers could stop him.

When the narcotics officers searched Landon’s dorm room they found over $22,000 in cash, dozens of empty vitamin bottles, and a four foot high stack of Muscle & Fitness magazines. But no painkillers.

His mother flew to Tennessee the next morning, bonded her son out, and flew back to Florida. When Lance told me about the arrest, I flipped out. “We should stop shipping to Tennessee or . . . at least limit the amount of—”

“Stop worrying!” said Lance. “My mom’s gonna take care of it . . .” Pretty Boy had been arrested half a dozen times and Miss Barabas had always managed to get him off. “He’ll be fine.”

The shipments were rerouted to Justin’s luxury condo in downtown Knoxville and scattered among several other distributors. The oxycodone pipeline continued to flow.

HE WOULDN’T STOP. Lance hired Larry the “Lineman,” his 400 pound brother to help him coordinate the shipments and launder the cash. They looked like Rob and Big walking around together. Like a real drug kingpin and his personal body guard. He was blowing money and throwing parties every weekend; knowing the Lebanon Police Department had arrested his brother.

In late June of 2009, Lance threw one of his Blow style parties at Victory Lofts. There were silver trays of cocaine and goblets of roxies and oxys being passed around. It was a bunch of college kids smoking weed and drinking out of Jägermeister keggerators. Lance spread a hundred grand out on his king-size bed and let a dozen drunken sorority girls snap photos of one another rolling around naked in the cash. Then they posted them on their Facebook pages. Coeds were getting fucked-up on pills; posing Charlie’s Angels style for photographs, wearing lingerie, holding Lance’s assault rifles and hand guns.

Around 11 o’clock, Lance and I were smoking a blunt on the balcony. “Bro,” said Lance, “you’ve gotta get a place here.”

My associates were all living in posh apartments and condos, but I’d never moved out of my grandmother’s spare room. “She’s seventy-seven-years-old, bro. I can’t leave her.”

FIVE HUNDRED MILES AWAY, the manager of Justin’s complex knocked on his door, in response to a noise complaint. He asked the college student to turn down his music; just before the wrestler closed his door, the manager noticed a Tech-9, laying in a duffel bag full of cash, sitting on the floor. He immediately called 911 and five minutes later, two Knoxville Police Officers knocked on Justin’s door. The wrestler yanked open the door and the officers immediately saw, not only the weapon and cash, but drug paraphernalia in plain sight. They searched the residence and found bags of Roxicodone, OxyContin, marijuana, an assortment of steroids and an empty prescription pad.

When the Knoxville Police Department narcotics officer got Justin alone in a downtown interview room and told him he was looking at a 30 year sentence if he didn’t start talking—Justin spilled everything. The pill mills. The scripts. The shipments. The money. Everything. Sometime around 1:00 a.m., the officer said, “I’m gonna have to call the DEA . . . This is bigger than I thought.”

The following morning, around the same time we were lying on a Florida beach recovering from the party, Justin was pouring his guts out to a half-dozen DEA agents and Assistant U.S. Attorneys in Tennessee.

The next day, Justin told Lance and I that he’d been arrested for a minor drug offense. Lance flew to Tennessee and gave Justin’s dad $50,000 to pay for a lawyer. The lawyer they hired, in turn, convinced Assistant U.S. Attorney David Lewen not to indict Justin, in exchange for setting up Lance and his Florida associates.

Shortly after that meeting Justin told Lance, “I’m too hot; I think the DEA might be watching me.”

“I understand,” said Lance. “Cool off for a couple months.” Justin then introduced Lance to one of his Tennessee associates, Dustin Wallace, and suggested Lance start shipping the drug packages to Dustin.

Over the next several months, using court ordered wire taps, the DEA listened in on hundreds of drug transactions conducted between Dustin, multiple Tennessee co-conspirators, and several of his Florida associates. Those calls quickly led to the DEA tapping all “Barabas associates’ phones.” They started following us, staking out our houses, and taking pictures of us going in and out of dozens of pill mills and pharmacies; and FedEx, UPS and DHL offices.

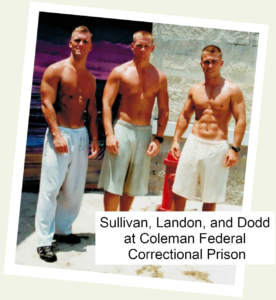

ON OCTOBER 20, 2009, Lance, Landon, and Larry Barabas, myself, and Richard Sullivan were indicted by a Knoxville, Tennessee Federal Grand Jury, along with nine other Tennessee co-conspirators.

WITHIN DAYS OF THE INDICTMENTS, Lance overnighted around 640 oxycodone to Dustin. However, the package disappeared off the UPS tracking page. Lance contacted UPS’s customer service and—after several calls—they told him the delivery truck had been in an accident. “They said there were packages all over the road,” Lance told me. “It’ll take a couple days to sort it out.”

“That doesn’t make sense Lance. Something’s wrong.”

“Nothing’s wrong. Stop worrying.” In fact, the painkillers had been seized by the DEA. The next day, Lance overnighted a second package containing 1,000 oxycodone tablets, to James LaPointe, one of Dustin’s Tennessee distributers. He slipped a couple roxies in his mouth and headed to the University of South Florida. Lance was transferring to USF and was in the middle of suffering through “hell week” as a Phi Delta Theta pledge.

ON OCTOBER 27, 2009, around four o’clock in the morning, dozens of DEA agents and local police officers in Florida and Tennessee assembled near their respective targets in preparation of operation “Oxy Rush.” They briefly reviewed tactics, verified photographs of the subjects and coordinated the multi-state raids.

At the predawn hour of 5:30 a.m., the DEA began executing their arrest warrants. Lance and roughly 30 soaking wet wannabe frat boys were doing calisthenics in their boxers on the front lawn of the fraternity house. The group was lit by flood lights and in the middle of doing jumping jacks, while a dozen Phi Delta Theta brothers hosed them down, yelling insults at the pledges. That’s when roughly 20 DEA agents pointing M-4 assault rifles, wearing black Kevlar-vests and masks, swarmed in screaming, “Down on the ground! Down on the ground!”

As the stunned students dropped to the lawn, the senior brother spun around and snapped, “Woah, woah, this is private property! You can’t—” The lead agent slammed the butt of his M-4 into the senior’s stomach, barked, “Down on the ground punk!” and the student hit the grass. The entire group was in the middle of being zip-tied face down in the lawn, when one of the agents growled, “Who’s Barabas?” And Lance thought, Oh shit, that ain’t good.

As he was loaded into a Suburban, in his sopping wet boxers, Lance looked at the fraternity house and thought, That’s too bad, I was a shoe-in. He was supplying half the brothers with painkillers.

When the DEA searched Lance’s loft they found his .308 Remington sniper rifle, AR-15 Bushmaster, Sig Sauer assault rifle, Glock .45, and a Smith & Wesson 9 mm, along with extra magazines and boxes of ammunition. They even grabbed Lance’s money counter.

Thirty miles away, in Hudson, a second group of agents surrounded Larry “The Lineman’s” house while the lead agent banged on his front door. Larry’s pregnant wife made the mistake of opening the door for the agents, and she and Larry were forced to the carpet and cuffed.

Around the same time agents arrested “Pretty Boy” Landon coming home from the Hard Rock Casino, and they grabbed Richard at his house.

Across Hudson, half a dozen DEA agents raided my grandmother’s house. Once they cuffed me, the agents asked, “Is anyone else home?”

I told them my grandma was home, “But she’s seventy-seven-years-old. Please don’t wake her up.” The agents searched the premises and found 1,000 pills, $80,000 in cash, and a safety deposit box key. When Agent Tim Lutz asked what the key went to, I told him, “I’ve gotta box at Wachovia Bank.” He got this big grin on his face and I should’ve known right then something was wrong.

Two hours later—around 7:30 a.m.—Agent Lutz had the New Port Richey Wachovia manager open the bank. The agent seized roughly $12,000 from my deposit box and told me, if I emptied out my checking and savings accounts of their combined $10,000 balance, he’d let me keep the $12,000 I had in CD’s. “Or . . .” said the agent, “I’ll come back with a warrant and seize it all.”

I closed out both accounts and handed it over to the agent. The DEA seized over $100,000 in cash.

Within hours, the five of us were standing in front of a federal magistrate judge requesting bond. “Your Honor,” said the Assistant U.S. Attorney, “Landon Barabas is already on state bond for a Tennessee arrest last year… and—fresh out of rehab—he just tested positive for benzos, marijuana, opiates, and cocaine.”

The judge scowled at Landon and growled, “You need to sober up young man.” The prosecutor then said, “Douglas Dodd was caught with several assault rifles, pills, and over twenty thousand dollars.” That’s when I realized the DEA hadn’t turned in all the cash they’d seized. “We’re charging Lance Barabas as a kingpin, your Honor. When the DEA searched his downtown loft, they seized an arsenal large enough to take on a small army . . . He’ll be lucky to be out of prison before he’s forty,” he said. “We’re requesting no bond for these three defendants.” Larry and Richard’s parents had to put up their houses to get them bond.

THE SEVERITY OF THE SITUATION didn’t really sink in until the U.S. Marshals transported us to Tennessee. As the prison bus pulled on to the tarmac at Tampa International Airport, we saw over thirty Marshals with shotguns leading over one hundred cuffed and shackled inmates off a Boeing 737. Everyone was wearing white t-shirts, khakis, and orange canvas shoes. With Nazi-like efficiency, the Marshals called out names and numbers, corralling the convicts onto multiple buses. That’s when it hit us. I looked at Lance and said, “We’re fucked!” He just stared out the window as the Marshals marched another large group of inmates into the plane.

Once we got to the Federal Holding Facility in Knoxville. I started looking for an attorney. At the time of my arrest, I had over $100,000 in pills out on consignment. God knows what Lance had. Once our distributors heard we’d been arrested, they started throwing away their prepaid cells and blocking our calls. Drug dealers and junkies aren’t exactly known for paying their outstanding debts.

It took me over a dozen calls to scrape together $42,500 needed to hire a federal criminal defense attorney. At our first meeting, my lawyer told me that trial wasn’t an option. “You’ve got over a dozen co-defendants that’ll probably testify against you. And the Assistant U.S. Attorney’s asking for twenty years… Or you can cooperate.”

“Twenty years?”

“Cooperate,” he said with a shrug, “and you might get five years.”

Lance was furious. He’d recently read, Busted By The Feds, an instructional guide to the federal sentencing system and was certain the most any of us could get was five years. Alone in our cell Lance told me, “There’s no reason to cooperate, bro. They can’t give us that kind’a time.” But his attitude changed dramatically after he spoke with his attorney. “If I cooperate,” said Lance after returning from his first attorney-client meeting, “he might be able to get me twelve years . . . maybe.”

ONCE WE’D ADMITTED OUR INDIVIDUAL ROLES in the drug and money laundering conspiracy, the probation department prepared Pre-Sentence Investigation Reports on each of us. The reports calculated what each defendant should get based on the Federal Sentencing Guidelines. 99 percent of the time judges follow the PSR’s recommendation—Lance’s recommended a 30 year to life sentence. When he got it in the mail Lance actually laughed, “That’s gotta be a mistake, right? They can’t actually give me a life sentence?” I almost cried for him. I loved Lance like a brother, and he was looking at 30 to life for illegally selling prescription drugs. The same thing that large wholesalers get caught doing—on a massive scale—all the time. But you don’t see any CEO’s doing 30 years to life or even 30 days.

Lance looked at me, in the dimly lit cell, and said, “Thank God they don’t know about Florida and Alaska.”

Several months later, we pled guilty. Roughly a week later, Assistant U.S. Attorney David Lewen pulled everyone out of our cells, one-by-one, and asked if any of us knew James LaPointe—one of our 14 co-conspirators. No one but Lance knew LaPointe. “He was one of Dustin’s dealers,” said Lance. “But I’ve never met him.”

“Well,” sighed the U.S. Attorney, “LaPointe’s going to trial and Dustin is going to testify. I need someone to back up the fact that LaPointe was receiving oxys for distribution from Dustin . . .” Lance told the prosecutor he hadn’t been at any of the meetings between Dustin and LaPointe, nor had he seen LaPointe accept any pills. “You need to think about that,” said Lewen. “You’re looking at thirty years.”

“What do you want me to do . . . lie?”

“No,” snapped the U.S. Attorney, “I want you to do thirty years. What do you want to do?”

“But, I . . .” Lance took several quick breaths, thought about his brothers, his friends, and the 30 years. “I wasn’t there. I wouldn’t know what to say.”

“Don’t worry about that,” said Lewen, “we’ll work it out.”

When Lance got back to the holding facility, he told me about the conversation and asked, “What should I do?”

“As your friend, I’m telling you, you need to do whatever you have to . . . to get that thirty years off your back. If you don’t, someone else will.”

LANCE AND DUSTIN were brought to the U.S. Attorney’s Office and prepped for the trial by Lewen. They ate pizza, chicken wings, and drank Mountain Dew for two days, while they got their stories straight.

In the middle of July, Lance testified in United States v. LaPointe that he and Dustin supplied LaPointe with Roxicodone and OxyContin for distribution and sale. LaPointe was facing 20 years, but he only got sentenced to 63 months.

As a result of Lance’s testimony, Assistant U.S. Attorney Lewen asked for the judge to depart downward from the PSR’s recommendation of 30 years to life. “But your Honor, keep in mind that Mister Barabas was the kingpin of a multi-state oxycodone criminal enterprise,” said the prosecutor, “with sales in excess of a million dollars in East Tennessee alone . . . We’re asking for two hundred and thirty-seven months (19 years and nine months).” But, Lance got lucky, and the judge sentenced him to 15 years.

THEY GAVE HIM 15 YEARS. He was 22-years-old, and he’d never been in trouble before. “Pretty Boy” Landon got 72 months, Larry “The Lineman” got 84 months, and “Dirty Dick” Richard got 35 months.

AT MY SENTENCING on September 21, 2010, AUSA Lewen requested the judge depart downward from the PSR’s recommended 121 months to 91 months for my cooperation. Standing in the courtroom full of my family, my attorney pled for a lesser sentence. “At a very early age, Mister Dodd was surrounded by drugs, alcohol, and abuse . . . he was physically abused by his mother as well as her two husbands and boyfriends.” At that point my mother abruptly stormed out of the courtroom. I looked back as the door slammed behind her and thought, That figures. “We’re asking for a fifty percent reduction and a product of environment variance based upon Mister Dodd’s childhood of twelve months . . . down to forty-eight months.”

My voice cracked as I addressed the court. “I got on the wrong path,” I said. “I figured I could make some money by the time I graduated college, and I went about it the wrong way.”

The judge agreed that my childhood was “best described as traumatic.” He’d reviewed over a dozen letters from my family asking for a light sentence. “You excelled academically and athletically. Unfortunately, you got involved in drugs… These prescription drugs are our number one problem in East Tennessee, and you were feeding the problem.” He sentenced me to 80 months (six years and eight months) of incarceration in the Federal Bureau of Prisons.

MY MOTHER COMES UP every few months to see me at the Coleman Federal Correctional Complex in Coleman, Florida. We spend most of our visits bickering about her 25-year-old former heroin addict boyfriend. She’s constantly telling me—her son who’s in federal fucking prison!—how hard her life is—It’s all about her!

When I mentioned I was writing a memoir, she snapped, “Why, so you can tell everyone what a horrible mother I am?!”

“Well,” I growled back, “if it walks like a duck and quacks like a duck . . .”

I’M SCHEDULED TO BE RELEASED in October of 2014. I’ve learned a lot from this experience. I’ll never sell drugs again, but I’ll never be able to look at another vitamin bottle without wondering how many painkillers I can fit into it, either.