A CHUNKY EFRAIM DIVEROLI—the real life gunrunner played by Jonah Hill in the movie War Dogs—sat opposite myself, Matthew Cox, and my literary agent, Ross Reback. To be perfectly transparent, I should mention, although I’m a true crime writer, at the time I was also a federal inmate. Like Diveroli, I was sheathed in a hunter green prison issue uniform. There were approximately one hundred inmates and their guests squeezed into the rectangular room; their chattering voices echoed off the walls and barred-windows. Two husky Federal Bureau of Prisons’ correctional officers were perched behind a desk; their eyes pinged between the occupants.

I listened to Reback pitch Diveroli on the idea of a partnership. He intended to obtain a publishing deal for the book that I was supposed to write, and two, to sell the film rights to the book in the hope of getting a movie made.

Understand that a year earlier Rolling Stone had featured the article Arms and the Dudes, written by contributing editor Guy Lawson. He’d based the piece on Diveroli’s business partner, David Packouz’s version of their shared experiences. Subsequently, the film rights were sold to RatPac Entertainment-Warner Brothers Pictures.

Diveroli asked Reback, “What if Warner makes a movie; what if they beat us to the punch?”

“Then we sue them for theft of intellectual property.”

The comment struck me as odd since I had only started writing the manuscript—i.e., the intellectual property—which would become Diveroli’s true crime-memoir. “How’re you gonna sue Warner,” I queried. The studio was developing their project based on the Rolling Stone article not my unrealized manuscript. “I’m nowhere near being finished.”

Sitting in the bowels of the largest prison complex in the United States, that was where the genesis of the scheme to scam Warner Brothers out of millions was conceived. And yes, they pulled it off.

“CONFIDENCE MEN ARE THE ELITE of the underworld. They have reached the top of the grift,” says David W. Maurer, PhD in his book, The American Confidence Man.

MY NAME IS MATTHEW COX and I’m a con man. I served a lengthy prison sentence at the Federal Correctional Complex in Coleman, Florida, for a slew of bank fraud related charges; and I’m 100 percent guilty of them all. As prisons go, Coleman wasn’t a bad one. The complex was clean and the inmates were mostly nonviolent. Mostly.

I LOVE MOVIES. In the early 2000’s, in commemoration of Quentin Tarantino’s movie, Reservoir Dogs, I created nearly a dozen synthetic identities: Lee Black, Michael White, Brandon Green, and William Blue, among others. Using these identities, I was able to convince several of the nation’s banks to lend my “borrowers” in excess of $11.5 million. Life was good, but it didn’t last.

Days before an FBI raid, (and my inevitable arrest) I fled Florida.

“THE GUY WAS GOOD. Very good,” said Gale McKenzie, the lead U.S. prosecutor on my case, during an interview with the Atlanta Journal-Constitution. The number of banks, the amount of the identities used, and the sophistication of the scheme, made the case very unique.”

IN THE FIRST CLASS CABIN of a commercial jetliner traveling over the Gulf of Mexico, my brother-in-law, Jack Townsend, was making small talk with his client, Ross Reback. Among other things, Reback fancied himself a big-time Hollywood player. He’d been mildly successful, selling one of his many reality TV concepts to a major network. However, during the course of pitching numerous other ideas, the entertainment agency representing him had brokered a deal with Oscar De La Hoya for a reality TV show, The Contender.

Coincidently, the premise was similar to one of Reback’s own concepts. Seizing the opportunity, Reback sued the network, his agent and the entertainment agency for theft of intellectual property. After a year of litigation, the agency buckled and settled the lawsuit.

Townsend and Reback were traveling to Los Angeles for the sole purpose of finalizing Reback’s lawsuit when Townsend inquired, “What’s your next project?”

“I’m not sure,” admitted Reback. “Have you been reading the St. Petersburg Times’ articles on this mortgage broker scamming banks?” Reback detailed my exploits and said, “It’s a Catch Me If You Can-story.” Townsend remained stone-faced. “Anyway, it’d make a great movie.”

“Uh huh,” grunted Townsend. “His name is Matt Cox… He’s my brother-in-law.”

IN DECEMBER 2005, Efraim Diveroli, a chunky Jewish kid from Miami Beach, was bragging to a friend, David Packouz, about how much money he was making selling arms.

Understand, Diveroli’s uncle had gotten him into the weapons business as a teenager. Diveroli had then begun bidding on government “Solicitations” for weapons and ammunition through FedBizOpps. One small contract turned into two, then three, and before long Diveroli was acquiring multi-million dollar deals.

Packouz agreed to partner with Diveroli, and the pair began bidding on government solicitations out of Diveroli’s one bedroom apartment.

Shortly thereafter, they were awarded a $298 million contract. Specifically, the U.S. Army needed to supply the Afghan National Army with ammunition for Soviet-style weapons.

Diveroli and Packouz began negotiating deals with former-Soviet Bloc countries throughout Europe.

APPROXIMATELY THE SAME TIME Diveroli and Packouz were flying tons of cargo into Afghanistan, I was in Nashville, Tennessee, utilizing the stolen identity. By mid 2006, I’d conned local lenders out of nearly $3 million.

Then, in November, Fortune magazine ran an article on my exploits. Days later, I discovered a blog discussing an upcoming episode on Dateline focusing on my schemes. My face was about to be broadcast into living rooms across the nation.

I grabbed a duffle bag full of cash and a passport issue in the name of a fake identity. But it was too late.

November 16, 2006, the Secret Service arrested swooped in and arrested me. A year later, I was sentenced to twenty-six years.

HERE IS WHERE DIVEROLI and Packouz got into trouble. In March 2007, Diveroli discovered Albania was sitting on a stockpile of AK-47 rounds. Enough to fulfill his entire task order.

What Diveroli didn’t know was that from the 1950’s through the 1970’s, the former Communist government had received the bulk of its ammunition from the People’s Republic of China. Unfortunately, the U.S. government had an embargo on all Chinese weapons and munitions.

Despite knowing this, Diveroli negotiated a deal with the Albanian. He repackaged the AK-rounds and began shipping the embargoed ammunition.

Everything was working out, however, as soon as the money began to pour in Diveroli began to question his and Packouz’s arrangement.

AS A RESULT OF A FALSE COMPLAINT filed by a competitor, Diveroli’s office was raided on August 23, 2007, by agents with the military’s Defense Criminal Investigative Service.

THE NEW YORK TIMES ran an article entitled Supplier Under Scrutiny on Aging Arms for Afghans, on March 27, 2008. The article described how Diveroli was gobbling up munitions through Eastern Europe to fulfill his contract as well as his method of repackaging Chinese ammunition—a violation of Unites States law. All in order to mislead the Army as to the product’s origins.

They questioned how a twenty-one-year-old with a staff of twenty-somethings could handle so much government work.

PACKOUZ WAS SENTENCED to seven months of home confinement; Diveroli, however, on August 23, 2011, received six years to be served in the Federal Bureau of Prisons.

THE LOW SECURITY PRISON at FCC Coleman, that’s where I met Efraim Diveroli. I had read the article in Rolling Stone magazine, Arms and the Dudes, by Guy Lawson months earlier. The story—primarily based on David Packouz’s version of the events—chronicled Diveroli and Packouz’s adventures as stoner-international-arms-dealers.

I was in the middle of working on my own memoir at the time, so I approached Diveroli about writing his story.

“I’ll think about it,” he said with little sincerity. “I’ll let you know.”

MY BROTHER-IN-LAW, Jack Townsend, and his client, Ross Reback, waited in the prison’s visitation room.

Weeks earlier, I’d mailed Reback a copy of my manuscript. After reading the story, he wanted to represent me.

Reback said all of the things a budding writer wanted to hear. I liked him immediately. He was a self-aggrandizing narcissist, but in a great way. I was captivated by his enthusiasm and knowledge of the literary world and the film industry. By the end of the visit, I was sold.

SOMETIME IN THE AUTUMN, I was rushing across the prison’s compound in the direction of the library when Diveroli stopped me. he excitedly informed me that Lawson had sold the film rights to the Rolling Stone article, Arms and the Dudes. RatPac Entertainment/Warner Brothers had bought the rights and they were planning on making a movie.

“Todd Phillips, the guy that made The Hangover movies, is gonna direct it,” said Diveroli. “That’s pretty cool, right?”

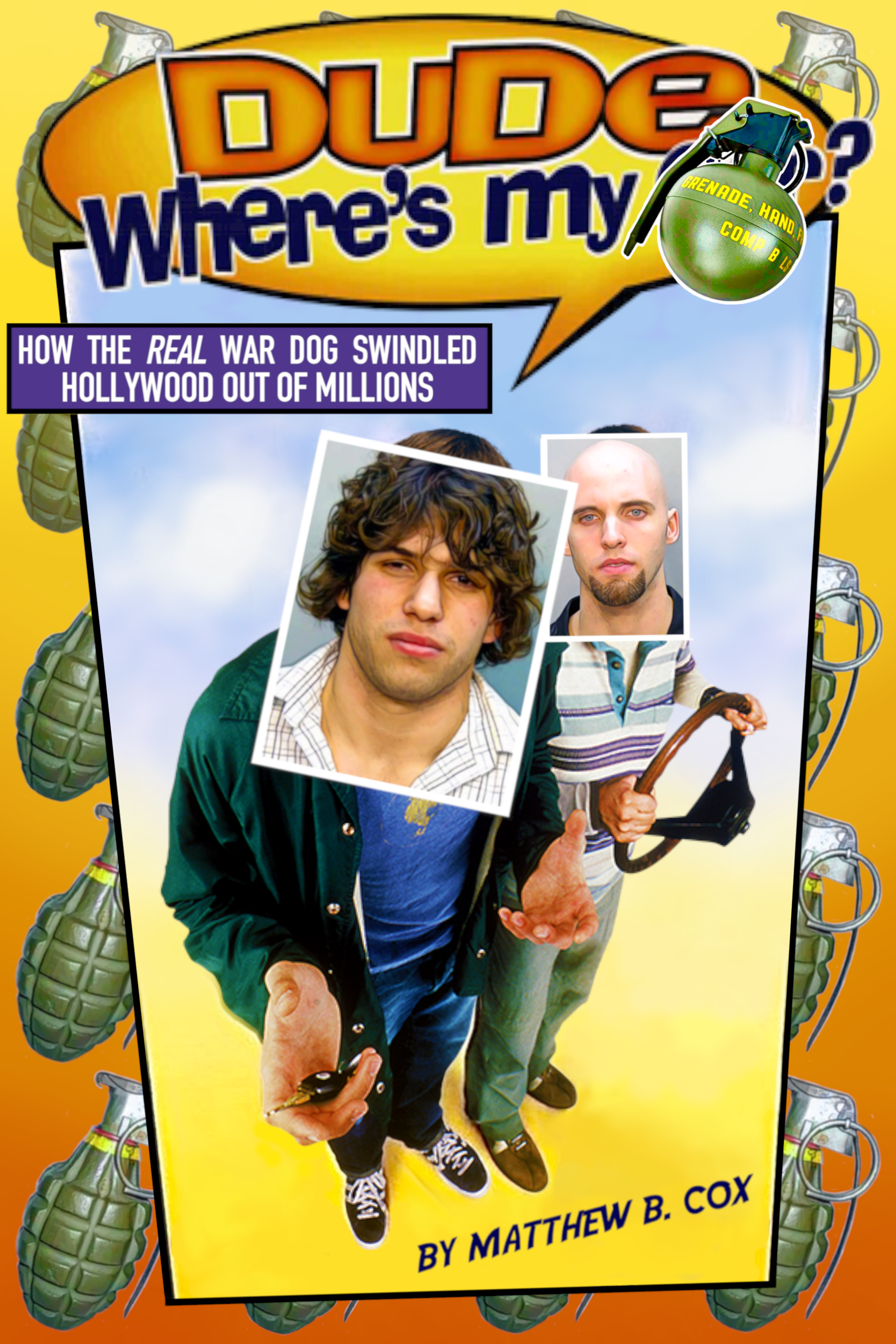

Genuinely shocked, I replied, “You seem like a sharp guy Efraim, but this isn’t cool. Have you ever seen The Hangover movies; Phillips is gonna make a movie called Dude, Where’s My Hand-Grenade. Your name’s gonna be synonymous with Jeff Spicoli from Fast Times at Ridgemont High. You’re gonna be a joke…” The elation faded from Diveroli’s face and I added, “You just seem smarter than this.”

I turned to walk away and Diveroli yelped, “When can we start?!”

Over the next few months, I wrote an outline chronicling the former-gunrunner’s exploits. As I was wrapping up the outline, Diveroli asked if he could read my manuscript.

A week later, he handed it back and said, “l want you to write my memoir.”

I had already decided that I wanted to start writing prisoners’ stories and Diveroli’s story was larger than life. It was everything I loved about true crime.

“Partner?” I asked.

“Of course,” Diveroli replied, and we shook on it.

Sometime in February or March 2013, I started working on the manuscript which would ultimately be titled Once a Gun Runner.

HERE IS WHERE IT GETS INTERESTING. A couple of months into writing the manuscript, I convinced Diveroli to meet my literary agent, Reback.

During that meeting, Reback laid out his credentials and his belief that he could help Diveroli and myself obtain a book and film deal prior to the other players.

OVER THE COURSE of expanding the outline into a manuscript—while sitting on a concrete table in the prison’s recreation yard—I gleaned a lot about Efraim Diveroli.

I began to notice that Diveroli’s particular motivation stemmed from more than simple greed. He took an unusual amount of pleasure out of beating someone out of their share.

Diveroli became disturbingly manic as he giddily yammered on about how he’d discovered how to bamboozle manufacturers. He laughed about running, what he described as a “legal bait-and-switch” when dealing with the U.S. government.

Eventually, as the weeks stumbled on, I got to Diveroli’s and Packouz’s dispute. Diveroli conceded that he owed Packouz millions—just as I had read in Lawson’s Rolling Stone article—however, his partner had no contract and Diveroli was in control of all of the funds. “Packouz was in a bad spot.”

“Why not just pay him?” I asked.

“Why, when I could pay a lawyer fifty or a hundred grand and fuck ‘im out of the money?” He burst into laughter as he was prone to do.

I must have appeared appalled at his callousness. “Don’t look at me like that,” spat Diveroli. “See, you don’t understand.”

But I did understand, and I knew that all of Diveroli’s promises—verbal or written—didn’t mean anything. My trump card, I told myself, is that Reback is involved. He won’t let this guy fuck me over.

“THE PRINCIPLES OF THE CONFIDENCE game are ancient,” Dr. Maurer informs us, in The American Confidence Man. “They are as old as civilization. However, the confidence games as we know them today have evolved.” Modem con men use a variation of the classic big-con games. All of these have certain similar underlying principles. “[T]he steps are these,” explains Maurer, “first, they locate a well-to-do victim.” Using an associate which is commonly known as a “roper,” the victim (or “mark”) is steered to the “insideman.” Ultimately, the mark is “fleeced.”

OUR NEXT MEETING—on May 2, 2013—as Reback and I waited for Diveroli, I mentioned that I was concerned with Diveroli’s character. “The guy hasn’t told me one thing that makes him sympathetic.” I explained that Diveroli had been running scams and selling junk to the government for years. “He’s a scumbag.”

“What’s most important is that you get the manuscript finished as quickly as possible,” replied Reback. He wanted to publishing Diveroli’s memoir before Warner began filming. “Do what you can.”

“The sex offender in Stranger Danger is more sympathetic.” I held Reback’s gaze for an uncomfortable moment. “l signed a contract with this guy…”

“I’m going to make sure you’re taken care of,” promised Reback. He informed me that if there was one thing, I could be sure of “it’s that you can trust me.”

The issue was time; Diveroli was scheduled to be transferred to the prison camp in Miami. That didn’t leave me much time to complete the manuscript.

“You know what,” grunted Reback, “the protagonist in Stranger Danger and Efraim have a similar story; their unexpected rags to riches rise. The nagging mother. The debauchery.” Reback suggested that I appropriate scenes from Stranger Danger as filler for Gun Runner, “and dramatize whatever you can to make Efraim sympathetic.” Reback’s only caveat was that I make sure to “incorporate Lawson’s factual-narrative.”

Minutes later, Diveroli slipped into the chair opposite Reback and myself. I listened to Reback pitch Diveroli on the idea of a partnership.

The former-gunrunner mentioned his pending departure for Miami, and Reback broached dramatizing, as well as fabricating, parts of the memoir in order to expedite the project. “Sure,” grunted Diveroli, dismissively. “l don’t give a shit; let’s just get it done.” He then asked Reback, “What if Warner makes a movie; what if they beat us to the punch?”

“Then we sue them for theft of intellectual property.”

The comment struck me as odd since I had only started writing the manuscript. “How’re you gonna sue Warner?” I queried. The studio was developing their project based on Lawson’s Rolling Stone article not my unrealized manuscript. “I’m nowhere near being finished.”

“But you will be. It’s not that hard to allege intellectual theft when there are competing versions.” Reback explained that once the manuscript was created it wouldn’t be all that difficult to manufacture a situation wherein, he and Diveroli could allege Warner had obtained the document. That, revealed Reback, would give them a basis to sue Warner.

Warner Brothers Pictures was the second largest studio on the planet. With a net worth in the billions, the studio made the perfect mark.

Reback then confessed that he’d sued a major television network and a prominent entertainment agency years earlier, using contrived evidence. All the while Diveroli grinned at the thought of filing a fabricated lawsuit. “l extracted a significant settlement,” Reback admitted, “and I have no doubt we can do the same with this project.”

Unlike Diveroli, I didn’t like the tenor of the conversation. It reeked of fraud. Diveroli, however, took to the idea immediately, informing Reback that he had a cousin that lived in Los Angeles. “He thinks he’s in the entertainment industry,” laughed Diveroli. “He’s a shmuck, but he knows a bunch ‘a people. We can make this happen.”

I DOUBLED-UP ON MY WORKLOAD to complete as much of the manuscript as possible. Still, the story was only two-thirds finished when Diveroli’s name appeared on the transfer or “pack-out” list.

The night before he left, Diveroli gave me a big bear hug, and a speech about our friendship. “You know me better than my own family knows me,” he said. “I don’t forget my friends, dude. I’m gonna be here for you.”

Weeks later, I emailing the completed manuscript, to Reback. Days later, I called him to discuss his thoughts and get whatever edits he had—I was certain Reback would want changes. Instead, he told me, “You knocked it out of the park.”

“THE MARK IS WARY GAME,” says Dr. Maurer. “Although marks may be plentiful, they do not walk heedlessly into the traps of the confidence men.” They must be located, points out the professor, then stalked before the kill. Once the mark is “sized up,” he must be steered to the insideman. This strenuous field work is done by the roper. “Ropers employ various methods of flushing their game, but most of them depend solely upon chance and casual contacts to provide them with marks.”

SOMETIME IN MAY—according to Reback—Diveroli reached out to his “schmuck cousin” in LA and requested he put him in contact with a Hollywood “insider” that could help him and Reback with their “project.” Someone that could get them close to a producer, director, screenwriter or executive at either RatPac Entertainment or Warner Brothers. It just so happened that Diveroli’s cousin knew the perfect person.

Elliott Kahn, a producer with Sunset Pictures, whose mother is Erica Kahn—the executive producer of the 2013 documentary Black Fish—contacted Diveroli and Reback. During their discussions, Kahn took the bait, and expressed his interest in pitching Diveroli’s life rights as described in the Gun Runner manuscript. Kahn believed that he and his business partner, Simon Spira (aka “Shimmy”) could move the project forward. Thus, becoming Diveroli and Reback’s unwitting ropers.

ON A CALL WITH REBACK in mid-to-late July, Reback states, “Shimmy’s father is Steven Spira, the President of Worldwide Business Affairs at Warner Brothers.”

“Okay,” I said. Both Kahn and Shimmy’s involvement made sense to me due to their contacts. “So, you want this guy to talk to his father or—”

“No, not exactly, it’s just…” Reback mulled over the question and continued, “Shimmy’s involvement opens up additional opportunities for us, that’s all.”

Reback explained that he’d asked Kahn to have Shimmy sign an NDA before allowing him to read the manuscript. After receiving the signed NDA from Shimmy on July 28, 2014, Reback emailed him the Gun Runner manuscript. Thereby setting the stage for Diveroli and Reback’s “confidence game.”

AFTER COAXING KAHN into steering Shimmy into position, Reback setup a three-way-conference call between himself, and his unwitting accomplices.

On August 15, 2014, according to Diveroli and Reback’s complaint, Reback asked how Kahn and Shimmy had progressed on garnering interest in the Gun Runner project. “Well,” Shimmy informed Reback, “based on my sources Warner is finalizing casting.” In fact, they’d already retained Jonah Hill to play Diveroli as well as retained Miles Teller as Packouz, “and the studio’s moving forward with the movie.”

“Who’s your source?” asked Reback, as if he didn’t already know.

The unsuspecting Shimmy announced, “My dad is Steven Spira; he’s the President of Warner’s business affairs.”

At this point, Reback feigned shock at the “revelation.” He went on to get upset that the Gun Runner manuscript was in the possession of one of Warner’s presidents. “If I’d known who Shimmy’s father was,” he snapped at Khan, “I’d have never let you send him the manuscript.”

Completely caught off guard, Kahn replied, “It wasn’t my place to say who his father was.”

Reback abruptly ended the call. He had everything he needed to sue Warner—a solid connection between Warner and the Gun Runner manuscript. It had played out perfectly.

Reback immediately began interviewing multiple attorneys in anticipation of the intellectual theft lawsuit.

Diveroli got out of prison.

WITH THE PIECES OF DIVEROLI and Reback’s confidence game arranged, Diveroli stopped all communication with Reback—he stopped returning emails or voicemail messages.

During a phone call sometime in late 2014 or early 2015, Reback stated that there was no way to pitch the story without Diveroli.

Weeks later, on February 1, 2015, I penned a harshly worded letter in which I stated “I think you guys have come to a point where someone needs to cut through all the crap and point out the obvious.” Due to Lawson’s soon-to-be released book by Simon & Schuster and the current Warner Brothers movie Gun Runner was “dead in the water.” I continued, “[s]uing Warner Brothers and Simon & Schuster isn’t going to work; they haven’t done anything wrong… It’s a waste of time and money.” Diveroli’s only real option—in my humble opinion—was to self-publish the memoir, hire a publicist, and do interviews with The New York Times, Variety, The Hollywood Reporter, et cetera. “While you and Ross [Reback] are talking to lawyers and chasing deals you’re missing a major opportunity.” I told Diveroli to contact Reback and follow the plan we’d originally laid out.

Approximately two weeks later, during a phone call with Reback, he informed me that Diveroli had called him. “He apologized and gave me some story about going on a drug fueled bender, then he got your letter and it put everything into perspective for him.”

WARNER BROTHERS began filming the adaptation of Lawson’s article Arms and the Dudes in March 2015. Ultimately, they renamed the movie War Dogs.

REBACK FLEW INTO MIAMI to meet with Billy Corben and his partner the producers of the documentary Cocaine Cowboys, as well as a female producer with CNN. According to Reback, Diveroli had gotten drunk and shamelessly flirted with the woman from CNN; Regardless, she pitched them on a one hour documentary revolving around his writing of the Gun Runner manuscript while in prison, and, of course, his story.

Shortly after that meeting, Corben and his partner discussed their interest in the project. However, neither party could pay Diveroli. Unfortunately, Reback wasn’t interested.

“The advertising will drive book sales,” I explained during a call. “He’s gotta do CNN, come on, what’re we even talking about?”

“l don’t want to do anything that will jeopardize the lawsuit.”

YOU HAVE TO UNDERSTAND, I wasn’t sitting around idly waiting on Reback. I was actively writing other inmates’ stories. In fact, I’d just finished writing Generation Oxy, the story of Doug Dodd, a convicted drug trafficker. Dodd and his all-American high school wrestling teammates—turned oxycodone kingpins—had made millions working the Sunshine state’s murky world of illegal pill mills. The unlikely group of over-sexed teens shipped hundreds of thousands of prescription pain-meds, while simultaneously duping the DEA.

I managed to get the story featured in the April 23, 2015 issue of Rolling Stone. Subsequently, Michael De Luca with New Line Cinema optioned Dodd’s life rights/film rights. Ansel Elgort—the actor from A Fault In Our Stars and Babyface Driver—had even signed on to play Dodd.

Better still, I had managed to turn the publicity into a book deal with Skyhorse Publishing.

For the first time, in a long time, I felt like I’d accomplished something.

DIVEROLI AND REBACK had hired Robert Thornburg—a prominent lawyer in Los Angeles with the firm Allen, Dyer, Doppelt, Milbrath & Gilchrist, P.A.—to represent them in the lawsuit.

None of it made sense to me until late March when, during a call with Reback, he the literary agent explained that he believed that Shimmy had shared the Gun Runner manuscript with his father “the president of Worldwide Business Affairs at Warner.” Reback said it as if he were revealing new information. However, I specifically recalled Reback telling me back in July 2014, that Shimmy’s father’s position with Warner Brothers opened up additional opportunities for him and Diveroli.

“Uh huh,” I grunted my understanding.

“Neither Kahn or Shimmy mentioned that Steven Spira—a President with Warner—was his father,” he continued. Reback giddily explained that “luckily” he’d had both of them sign NDA’s. I, however, already knew this. “Shimmy still lives with his father; there’s no way he didn’t disclose the manuscript—this couldn’t have worked out better.”

That’s when I knew it was all a scam. A con game run by two accomplished confidence men.

DAY THE LAWSUIT WAS FILED—April 28, 2016—Reback, had arranged to have nearly all of the parties—Warner Brothers, RatPac Entertainment, The Mark Gordon Company, Todd Phillips, Bradley Cooper, 22nd and Green, Elliott Kahn, and Simon “Shimmy” Spira—served simultaneously.

The lawsuit alleged that due to the limited information contained in Lawson’s article about Diveroli, Kahn and Shimmy—acting as agents of Phillips, Cooper, and Warner—the Hollywood “insiders” approached Diveroli and Reback in order to obtain the Gun Runner manuscript. The information contained within the manuscript was then used to write the War Dogs screenplay.

IN EARLY AUGUST, I was seated in an area known as “Stonehenge,” just outside of the B-House building. The circular space consisted of a large concrete-slab, containing an outer ring of concrete seats surrounding concrete benches and tables.

“Cox,” said Dennis Caroni, an obnoxious inmate incarcerated for running a pill mill. As he approached the table, I noticed that Caroni was holding a copy of Ocean Drive—a large glossy Miami based magazine. “You making any money on the Diveroli book?”

“No.” I grimaced. “They’re still looking for publishers.”

He slapped the Ocean Drive onto the table and flipped open the magazine. “Are you sure,” he said, “cause this says he published.”

Sure enough, on one of the pages was a snapshot of Diveroli grinning ear-to-ear while holding a copy of Once a Gun Runner. Resting behind him were several hundred hardcovers. The caption directly under the photo read Efraim Diveroli at the 2016 Miami Book Fair.

Glaring at that photo, I felt like I’d had the wind knocked out of me.

Understand, the lawsuit was not only centered on Diveroli and Reback tricking Shimmy into taking possession of the manuscript, but also on the presumption that the film would contain similar scenes which they could attribute to the Gun Runner manuscript.

ON AUGUST 19, 2016, Warner Brothers released War Dogs in theaters across the nation. It raked in tens of million within its first few weeks—ultimately grossing over $100 million worldwide. However, the movie had very little similarity to Diveroli’s story.

During a call with Reback, the literary agent admitted, “The movie is a lot different than Gun Runner.”I could hear the stress in his voice. “There are invented scenes and… well it’s very different.”

In fact, it was so different that Diveroli and Reback’s high priced attorney, Thornburg, got off the case. The most likely explanation was that he refused to move forward with claims against Warner that he now believed were false and unsubstantial.

“EFRAIM’S BOOK IS A WORK OF FICTION,” David Packouz told a reporter with New Times magazine.

The article went on to cite Diveroli and Reback’s lawsuit, stating, “Diveroli says, he was tricked into leaking the manuscript to the studio. Two producers—Shimon Spira and Elliot Khan—approached him in 2014 about adopting his still-unpublished manuscript into a film, he claims. But Spira failed to divulge that his father was a high-ranking Warner Bros. exec. Diveroli claims the pair gave the book to the studio.”

MY BUDDY PETE, spent most of his time helping other inmates with their legal work. Thirty years ago, however, Pierre Rausini had been a twenty-something Los Angeles-based drug trafficker, making million. He and his associates drove luxury European supercars, lived in Beverly Hills’ penthouses, and dated Playboy models. But then, well, two FBI informants were murdered and Pete ended up with a very, very, long sentence.

I confided in Pete regarding Diveroli and Reback’s sham lawsuit, as well as the fact that they had not paid me for the book.

“They used the book that I wrote to sue Warner; the same manuscript that they stole from me,” I said. I then explained that—at Diveroli and Reback’s urging—I’d embellished and fictionalized a significant amount of the book Diveroli and Reback were pitching as The Real Story. “These guys are running a confidence game.”

HEREIN LIES THE RUB for Diveroli and Reback. Todd Phillips had only loosely based the screenplay on Lawson’s article, radically altering the events to such an extent that the film bore little resemblance to Diveroli’s “true crime-memoir.” In fact, in Warner’s motion to dismiss the lawsuit, they went so far as to characterize War Dogs as a fictionalized account of the story.

As a result of Diveroli and Reback’s blunder, they had no choice but to drop their theft of intellectual property claims. However, instead of calling it a day, Diveroli and Reback changed gears and hired a new attorney, Kenneth Turkel, with Bajo, Cuva, Cohen, Turkel, a prominent law firm in Tampa, Florida.

Ken Turkel had just won the privacy lawsuit against Gawker.com. As such, his client, wrestler Hulk Hogan, had been awarded $115 million. The award devastated Nick Denton’s media company, Gawker. No doubt, Turkel was hoping to do the same to Warner.

On November 3, 2016, the now-famous lawyer, filed a new lawsuit, alleging false advertising claims under the under the Lanham Act.

Specifically, the Lanham Act prohibits false advertising in connection with “commercial advertising or promotion.”

Turkel asserted an unfair competition allegation based on Warner advertising War Dogs as a true depiction of Diveroli’s story when it clearly was not. Additionally, Diveroli and Reback were suing for false advertising and related claims because Warner had promoted the film as telling the “true story.”

They described Warner’s misconduct in great detail, identified Warner’s false promotional materials, quoted several of Warner’s assertions that War Dogs was true and alleged that those statements misled consumers about the content of the movie which, Warner later conceded, was a fictionalized account. Turkel alleged that Warner’s false advertising and promotions were made to benefit its own economic interests by selling movie tickets to its film—because movies that are “true stories” sell better to the public.

The lawsuit further alleged that since it was selling a competitive product—Once a Gun Runner which detailed the “true” story of Diveroli’s adventures—Warner damaged Diveroli and Reback by falsely advertising War Dogs as the true story of those same exploits. As a result, Diveroli and Reback had suffered economic harm.

Ironically, in a twist unbeknownst to Warner, the foundational basis for the new claims was a lie.

“WHEN DOES TELLING THE TRUTH ever help anybody?” – Efraim Diveroli, War Dogs

“WHY DRAMATIZE IT,” I asked Pete, shortly after we learned of the new lawsuit. “The story—the true story—is amazing.”

“Think about it. Warner has never denied obtaining the manuscript. They may have actually obtained it exactly as Diveroli and Reback planned.” Pete surmised that once Warner had the manuscript, they may have used the document to rewrite the screenplay in order to eliminate any overlapping scenes. “They knew Diveroli was going to sue, so, they crafted the movie in such a way as to insulate themselves from any potential lawsuit.”

The more I thought about it, the more it made sense. If you go through the movie, scene by scene, it’s obvious that this is true. For example, the opening scene wherein Packouz was kidnapped and had a gun placed to his head, that never happened. I can go on and on: Diveroli never fired a machine gun to scare off drug dealers; Packouz never lived in a high-rise apartment building with his girlfriend; nor did he ever drive a Porsche—unless he was parking it for someone—neither did Diveroli. At the end of the movie, Packouz never met with Heinrich and he damn sure was never given a briefcase full of cash.

Despite this, Warner’s agents promoted the film as “the unadulterated truth.”

War Dogs’ screenwriter, Stephen Chin, in August 2016, misled viewers by stating he was “very interested in finding the real story… I saw these guys, Efraim and David, as a real way to tell an accessible story—as a way into the story about the war… So, I wanted to be deeply true to their story.” During that same month, the real life David Packouz described the movie as being “exactly how it happened.” On September 8, 2016, Todd Phillips promoted the film by stating that “truth is stranger than fiction,” and “it was really the reality, the idea that it was a true story that appealed to me.” He further emphasized, “[w]e got this article, this Rolling Stone article… it’s really about playing to the truth of it.” During Jonah Hill’s promotion of War Dogs, the actor made it clear that Warner’s intention was to market the film as a true story. “[It’s] just a story that’s so crazy you can’t believe it actually happened… And it’s all true.”

Warner placed a substantial importance on representing War Dogs as a true story to the public because it induces consumers to see movies. In fact, Phillips even stated that “the idea that this was a true story was for me the most interesting part about it.”

Stated simply, Warner knew it would make more money by marketing War Dogs as a true story instead of the work of fiction that it actually is.

“The Lanham Act states that a company cannot profit from knowingly marketing a product using false, misleading or deceptive advertising,” said Pete. Which according to Warner’s own admission within their dismissal motion is precisely what the entertainment company had done. “It’s potentially a mega-settlement, worth tens of millions.”

“It’s a fuckin’ scam,” I replied, “the book’s fiction. They’re running another scam.”

“Plus, they’re claiming deceptive and unfair trade practices, unfair competition.” Pete explained that the lawsuit was sound, with the exception of their misrepresentation of Gun Runner’s true nature. However, if I could prove that Diveroli and Reback had filed the copyright application for the purpose of manufacturing standing to bring a fraudulent lawsuit against Warner, they’d have unclean hands. “Legally, at that point, you’d own the copyright. You have to join this suit and dispute ownership of the copyright.”

WITHOUT A DOUBT, Diveroli is a sharp guy. When he convinced me to write his story, he knew that I didn’t have enough money to hire an intellectual property attorney, he knew the limitations of the Bureau of Prison’s legal research computer system, he knew the near impossibility of fighting a civil case while incarcerated, and he knew that I had nearly two decades left to serve on my sentence. But the one thing he couldn’t anticipate, was that I had no intention of serving my entire sentence.

The U.S. prosecutor in my criminal case, Gale McKenzie, requested that I participate in interviews with the tabloid news programs Dateline and American Greed. In addition, she asked me to help write an Ethics and Fraud course, which was then used to train the nation’s mortgage brokers. In exchange, she agreed to request the court reduce my sentence.

Despite fulfilling my part of the agreement, when it came to filing a motion to reduce my sentence, McKenzie refused.

Within weeks, I had spoken with two criminal defense attorneys in Tampa; each told me there was nothing I could do to force the government to live up to their promise.

That’s when I approached Frank Amodeo.

I FIRST TOOK NOTICE of Frank Amodeo shortly after he arrived at the low security prison in July 2009. Another inmate pointed to the disbarred-attorney and explained that he suffered from an extreme form of bipolar disorder with features of schizophrenia. In fact, Amodeo was so unstable, he had been declared legally incompetent.

Prior to his incarceration, Amodeo had devised a scheme to defraud the federal government out of nearly $200 million. He then began investing in companies with military application. Additionally, he backed a failed political coup to seize control of the Democratic Republic of the Congo. As crazy as this is going to sound, Amodeo’s goal was to take over the world.

Subsequently, the federal government arrested him, pumped the wannabe world leader full of antipsychotics, and sentenced him to over twenty years.

In his typical hypermanic fashion, the disbarred lawyer organized—from within the prison—the equivalent of a medium-sized law firm, utilizing the only employees available to him: inmates.

The megalomaniac and his minions cranked out motions on behalf of Amodeo’s one hundred plus incarcerated “clients.”

Within minutes of hearing my issues, Amodeo became indignant. “Don’t worry,” he told me. “I’m not going to let them get away with this.”

Amodeo and his associates spent nearly a year filing motions on my behalf; and, on October 8, 2013, the court reduced my sentence from 26 years to 19 years.

When I thanked Amodeo for his help, admitted that he’d expected a larger reduction.

“Yeah,” I snickered, “me too.” I had nearly a decade left to serve.

He nodded his understanding and said, “It looks like we’re going to have to eat this elephant one spoonful at a time.”

RON WILSON was a gruff old, confidence man. He’d been sentenced to just under twenty years for running a decade-long Ponzi scheme, thus bilking nearly 800 victims out of tens of millions. By the time I returned from court, Wilson had been at Coleman Federal Correctional Complex for roughly a year.

I used to walk the prison’s half-mile-track with Wilson sometimes. In an effort to reduce his sentence, Wilson was currently working the U.S. Attorney Office to prosecute several other fraudsters.

“They’re never gonna cut my sentence,” he grumbled. For months he’d been griping about how the Secret Service agents working his case despised him. “The thing I’ve hidden Ponzie scheme money.”

“Stop worrying.” I assured him if the government tried to withhold the reduction, I would have Amodeo force them to reduce his sentence.

We walked a lap in silence, nothing between us but the sound of the crushed shells underneath our sneakers. Then, Wilson turned to me and asked, “Can I trust you?”

It was a strange thing to ask a reputed con man. I specifically recall shooting Wilson a sideways glance and answering, “Probably not.”

He chuckled at that and admitted, “I put some money away.”

He proceeded to tell me that he’d entrusted roughly half a million dollars of Ponzi scheme proceeds to his soon-to-be-ex-wife and his brother.

A little over a month later, I mentioned it to my attorney. She made a few calls to the lead Secret Service agent on Wilson’s case, which led to the money being seized.

Shortly thereafter, Wilson, his soon-to-be-ex-wife and his brother were indicted. They all pled guilty, Wilson’s wife and brother received a one year probation. Wilson was sentenced to an additional six months.

Amazingly, once again, my prosecutor refused to reduce my sentence. This led me back to Amodeo; and after a visceral number of filings, Amodeo forced the government to file another reduction in my case. This time my sentence was reduced from nineteen years to fourteen years.

Amodeo and his staff had nearly cut my sentence in half. That was something that Diveroli hadn’t counted on.

THE PRISON WAS SERVING PIZZA and the cafeteria was packed. I was seated at a table with three other guys when Pete rushed up to me. “There’s a mediation!” he gasped. “Warner, Diveroli and Reback are going to settle.”

The parties were meeting on March 23, 2017 to mediate the claims.

“What does that mean?”

“Warner’s caving. They wanna discuss a settlement. If you don’t intervene in the suit now, Diveroli and Reback are going to get a settlement and disappear with the money.”

DAVID PACKOUZ—THE CHARACTER played by Miles Teller in the movie War Dogs—wanted to speak with me. Packouz was Diveroli’s previous business partner. He and another disgruntled partner, Ralph Merrill, were currently suing Diveroli over a contract dispute.

Wedged between two inmates at the bank of stainless steel phonebooths, I explained that Diveroli had run a bait-and-switch on me—luring me in as a “partner,” only to try and screw me out of our agreement.

“Yeah,” said Packouz, “that’s what he did to me over the Afghanistan contract. It’s pretty much his modus operandi.” Packouz asked if I would be willing to be interviewed by his attorney “and possibly be deposed.”

Diveroli had been released from prison, published the book that I’d written, and was actively working to screw me out of my share. “Absolutely,” I replied. “Bro, I’ll do anything I can to help.”

Eventually Packouz asked if Diveroli had ever confided in me. “Did he ever tell you why he did it; why he fucked me out of my end of the contract?”

During one of our many meetings on the recreation yard, I’d specifically asked Diveroli why he hadn’t just paid Packouz. “He said that he had an agreement with you, but once he started hiring employees, he realized that he could hire someone for considerably less money.”

“Do you have any idea how hard I worked on sourcing the munitions for that contract? How many hours a day I worked; for weeks and weeks,” he griped. “I worked with him when no one else would.”

“I understand. I did the same thing,” I admitted. “But he knew you guys didn’t have anything in writing and he was gonna owe you millions by the end of the contract.”

“He’s gonna fuck you over too,” mumbled Packouz, “just wait.”

USING A THIRTY-YEAR-OLD SWINTEC typewriter with no word processing function, Pete began typing out my motion to intervene in Diveroli and Reback’s lawsuit against Warner.

Days before the mediation, March 14, 2017, Pete and I filed my motion to intervene in Diveroli and Reback’s lawsuit against Warner. Within its body Pete exposed Diveroli and Reback’s plan to manufacture a falsified lawsuit against Warner, however, he didn’t reveal the connection between Gun Runner and Stranger Danger.

“DO YOU REALIZE HOW DEVASTATING that motion’s going to be to their case,” asked Pete. We locked eyes and burst into laughter.

“Can you imagine?” I replied. “I see Diveroli and Reback being led into Turkel’s office by a hot little secretary. Turkel is sitting behind his desk. He holds up the motion and says, ‘Devastating. This is absolutely devastating.’ Diveroli and Reback ask what their attorney is talking about and he says, ‘Your co-author, Matthew Cox, just snatched a twenty million dollar settlement out of our hands.’”

“You know Turkel had to ask them if the allegations were true.”

“I know, right?” I replied. “That had to be an uncomfortable conversation.” Turkel must have asked if they had arranged for Shimmy to request a copy of the manuscript—knowing he was the son of a Warner Brothers’ executive. “What a gut punch that must’ve been.”

Pete and I started laughing again.

Regardless of precisely how the conversation unraveled between Turkel, Diveroli, and Reback, what I do know is this, on March 20, my intervention caused Warner to cancel the scheduled mediation between the parties—permanently eliminating the mega-settlement out of Diveroli, Reback, and Turkel’s grasps.

WARNER’S LAWYERS—AFTER REVIEWING my claim—on June 20, 2017, moved to depose me. Specifically, based on the studio’s motion, “Warner believes that Cox holds information that is important to Warner’s defense of IE’s [Diveroli and Reback’s] remaining false advertising claims… Cox is a relevant witness in the case. Thus, Warner seeks to depose.” Because the judge hadn’t made a ruling on my intervention yet, Pete fought the request. In the course of the legal bickering, I began trading emails with Warner’s attorneys, Matthew Kline and Daniel Petrocelli with the law firm of O’Melveny & Myers.

“You do understand Petrocelli is Trump’s attorney, right?” Pete asked me, as we walked the prison’s half mile track in the smoldering Florida heat. He explained that the firm had over seven hundred attorneys. “It’s one of the largest, most prestigious law firms in the country.”

Their firm had thousands of years of experience and support staff with state-of-the-art legal software and equipment, while Pete was utilizing the expertise of a disbarred lawyer—who had been found to be mentally incompetent—and a thirty year-old beat-to-shit SwinTec typewriter.

I interjected, “Can you imagine how disgusted they’ve got to be, having to communicate with us?”

That night I called my brother, Mark. During the call he mentioned that he’d spoken to our brother-in-law, Jack Townsend, regarding the lawsuit.

“Jack said the law firm you guys are up against (the firm Diveroli and Reback’s retained in Tampa) are known for being particularly ruthless,” my brother admitted. “Seriously, the attorneys that work there are like, vicious—”

“Vicious, huh,” I grunted. “One of my jailhouse lawyers ripped off the U.S. government for two hundred million, then he turned around and tried to take over a fuckin’ country—the Democratic Republic of the Congo. The other guy is here for murdering two federal informants and dumping their bodies in a couple of dumpsters—more vicious than that?”

SHORTLY AFTER THAT CALL, given my allegations that I was the sole author and rights holder of the Gun Runner manuscript and that Diveroli and Reback had conspired to steal my copyright, Warner’s attorneys persuaded Judge Scriven that I was privy to “information that [was] important to Warner’s defense” and that I had “documents and information relevant to Warner’s case.” As a result of this, the judge granted Warner permission to depose me at the prison. Understand, Diveroli and Reback knew that during the deposition I would confirm the entire scheme to manufacture the lawsuit.

With the collapse of their case eminent, they pushed for a second mediation, which was scheduled for August 17, 2017.

Now I’m not certain whether Diveroli and Reback as well as their lawyers, Cohen and Turkel, were seated across the conference table from Kline and Petrocelli. Nor do I know if there were empty coffee cups and papers strewn across the table or if Reback had been fiercely negotiating for hours when he suffered a massive heart attack.

I can’t tell you if Reback died while lying on the conference room floor, in the ambulance or hours later at the hospital. What I can say is this, the following day, at 2:51 p.m., I received an email from my niece which read: “[J]ust heard that Ross Reback died last night. My dad told me. We don’t have any details yet, just heard and wanted to let you know.”

I was open mouth stunned. Although I was upset with Reback, I didn’t want to see any harm come to him.

THE DAY OF THE FUNERAL, well over one hundred mourners braved the Florida heat. Among the sea of grieving friends, family, and business associates sharing their memories of Reback were my brother-in-law and my sister, Helen.

“THE CONFIDENCE MAN PROSPERS only because of the fundamental dishonesty of his victim,” says Dr. Maurer. Specifically, the con man convinces the mark that he will make a large sum of money by dishonest means. “As the lust for an easy profit is fanned into a flame, the mark puts all his scruples behind him.” In the mad frenzy of cheating someone else, he is unaware of the fact that he is the real victim. “You can’t cheat an honest man.”

IN NOVEMBER 2017, I received an email from Diveroli’s attorney, Turkel, out of Tampa. He informed me that he was no longer representing Diveroli, and that it was his understanding that Diveroli’s new lawyer was Matthew Troccoli.

The federal court in Tampa, days later, notified me that both Diveroli and Warner had mutually agreed to drop their lawsuit. To me and Pete it appeared that due to Reback’s death the parties had decided to cut their losses. So, Pete tracked down Amodeo in his housing unit.

“They settled,” chuckled the disbarred-lawyer, as he read the motion to dismiss. However, the document didn’t indicate a settlement.

“How’s that possible?” Pete inquired. Warner knew that there was a dispute over the copyright ownership. If I were to win the claim, I would have standing for relief, not Diveroli.

“This Reback must have convinced Warner to settle the suit before he died.” As it turned out, Warner and Diveroli “dropped” their lawsuit.

The disbarred-lawyer thought about the factual allegations in my lawsuit for several seconds. He arranged the pieces and came to the conclusion that “because Warner promoted War Dogs as the true story in order to sell movie tickets—because movies that are ‘true stories’ sell better to the public, its advertising campaign caused damage to Cox, by cutting him out of the market place.” Consumers who desired to learn about Diveroli’s exploits were more likely to purchase a movie ticket to War Dogs rather than purchase the Gun Runner book; causing loss of sales and loss of professional credibility. “And that hasn’t changed. Unlike Efraim, we know Warner believes that Cox may very well be the rightful owner of the copyright. So, it’s in Warner’s best interest to settle with Efraim, and work with him to stop Cox. That allows them to continue to advertise War Dogs as a true story.” Amodeo added, “They would’ve had to have agreed to have the settlement held in escrow until Cox was taken care of. Diveroli must get a ruling on ownership of the copyright. Then, and only then, will Warner release the funds.”

Keep in mind that Amodeo’s assessment was only an educated guess. However, days later, Diveroli sued me in the Southern District of Florida’s federal court. Specifically, he wanted a court ruling on ownership of the copyright.

ON JANUARY 8, 2018, while Pete was composing my counter suit, I contacted my sister, Helen. During that conversation, I asked her if she’d found out how Reback had died.

“l think it was a heart attack,” she responded. Helen proceeded to tell me that she and my brother-in-law had attended Reback’s funeral, “You know the nicest thing about the service was that Jennifer * (Reback’s widow) told us that he had a great last day. He and a business partner had some big settlement in a lawsuit they’d filed against some studio. Ross was really excited about it.”

* Name has been changed.

Understand that, although my sister knew I was suing Reback and Diveroli, as well as Warner, she had no idea she was revealing anything of significance. However, it was confirmed that Warner had actually settled with Diveroli and Reback.

Minutes later, I regurgitated the call to Pete. We immediately tracked down Amodeo. The disbarred-attorney stood silently thinking about the case for a few seconds and said, “Five million; he got Warner for at least five million.”

MY RELEASE DATE WAS JULY 2019, however, in early 2018 my case manager informed me that I would, most likely, be leaving for a halfway house by the end of the year.

That night Pete and I sat in the prison’s library, and we went over example after example of scenes that I’d taken directly from Stranger Danger as well as scenes which had inspired scenes in Gun Runner. I pointed out characters and nearly identical dialogue I’d used to create the manuscript which Diveroli and Reback had presented in court as Diveroli’s true story.

Roughly an hour later, as Pete and I walked back to his housing unit I mentioned that it was very likely that Diveroli and Reback had misled their lawyers into believing that my claims were baseless. “You know what we ought to do?” said Pete. “We should send Troccoli a few pages of Stranger Danger along with the corresponding pages in Gun Runner.” He concluded that if Diveroli had misled his counsel, Troccoli would remove himself immediately. “He can’t go into court and take a position that he knows is a lie.”

“You want to get his lawyer to quit?”

“At this point,” chuckled Pete, “we want to make this case as difficult and expensive as we can for Diveroli. Forcing his attorney to quit will definitely throw a wrench in the machinery.”

Troccoli received the priority package containing the examples proving the fictionalization of Gun Runner on July 18, 2018. Nine days later, he sent me an email stating that he was withdrawing as Diveroli’s counsel.

The most likely explanation for this was that Troccoli, after going over the samples of Stranger Danger, decided that his client had misled him and the case was much less winnable than he’d previously been led to believe. Regardless of the specific reason, Diveroli promptly hired Ryan Clancy, a prominent attorney out of Miami to take over for Troccoli.

Of course, I immediately mailed Clancy a copy of Stranger Danger, but it had no effect on him, which could only mean that Diveroli had told him some semblance of the truth.

I traded emails with Clancy in regard to my counter-suit—which now included Warner and Reback’s Estate. As the exchange became heated, Warner’s attorney, Kline began emailing me as well.

Over the course of several weeks the two lawyers hit me with a barrage of emails. Each correspondence was designed to try and get me to settle the case.

“[W]e are prepared to offer you the sum that has been budgeted to defend against these claims,” stated Clancy. He then explained that the amount depleted each time an email was sent. At the rate of the exchanges, “I think you are going to end up with nothing but attorney fees against you.”

This caused multiple exchanges, but ended with this retort, “Warner itself conceded in its motion to dismiss [IE, Reback, and Diveroli’s] First Amended Complaint that War Dogs was a largely fictionalized account of Diveroli’s exploits. Now that is certainly not what Warner’s advertising led the public to believe.” In fact, I was the individual that alerted Kline to the fact that IE, Diveroli, and Reback were committing a fraud on the court and that I had proof of my allegations. “Notwithstanding these facts, Warner chose to pay IE [and Diveroli] off.” Why Warner paid off Diveroli was clear, I wrote. By paying off Diveroli “Warner is now in a position to continue DECEIVING the public into believing that War Dogs is a true story”—a blatant violation of the Lanham Act.

Despite additional exchanges, and my willingness to discuss settlement, Diveroli’s attorney never made a reasonable offer.

“A CONFIDENCE MAN, once he has established himself, seldom changes his profession for another in the underworld,” Dr. Maurer informs us. The con man moves from one confidence game to another. “So long as there are marks with… money, the law will find great difficulty in suppressing confidence games.”

IN EARLY SEPTEMBER 2018, Pete researching civil conspiracy law, when stumbled across multiple law suits wherein—after extracting a settlement from Warner—Diveroli had turned around and sued: Simon & Schuster, Google, NBCUniversal, Apple, Amazon.com, Rolling Stone, Guy Lawson, Hulu, and CNBC LLC; alleging the same claims that he’d alleged in the Warner lawsuit. The same claims that he’d admitted had no merit.

That night, Pete and I walked the compound and discussed Diveroli’s newest lawsuits. “It makes perfect sense,” I said. “He’s perfected the scam and now he’s duplicating it.”

“He must think Clancy’s going to be able to get the case dismissed,” said Pete. We talked about that for a while and came to the conclusion that because we hadn’t informed the court of the specific nature of Diveroli and Reback’s fraud, Stranger Danger, Diveroli was under the impression that the attorneys for his most recent marks would never discover he was using a fabricated book to extort settlements from their clients. “I think we should notify each and every one of the defendants’ attorneys of what Diveroli is up to. It’ll devastate his case.”

“If Diveroli isn’t going to make me a reasonable offer,” I replied, “I’m more than willing to crush any chance he has of continuing his scam.” It only seemed fair.

Pete spent a few days drafting a lengthy email on my behalf. It briefly covered who I was and gave a bit of background on the current case and my claim as the true copyright owner. However, Pete hammered away on the fraud that Diveroli was committing against their clients. “Your client is a victim of a scheme hatched by Diveroli and Reback while Diveroli was still serving his prison sentence at the Coleman Federal Correctional Complex for defrauding the United States.”

The email explained that I was “the author of a novel titled Stranger Danger which, along with Gun Runner, is relevant to your lawsuit. Notably, Stranger Danger is entirely a work of fiction.” I explained that I was present during the meetings when Reback and Diveroli hatched their scheme. “[E]veryone seems to have taken at face value that the Gun Runner memoir tells Diveroli’s true story, i.e., that the book presents a factually accurate version of Diveroli’s exploits. That’s the foundational fraud in IE’s scheme.” In reality, there were “entire passages in Diveroli’s memoir which are literally taken word-for-word from the Stranger Danger manuscript. There are also numerous scenes in Gun Runner that are based on scenes I invented for Stranger Danger.”

I closed out the email with “I did not write the Gun Runner manuscript so that it could be used to engage in criminal conduct or serve as a basis for fraudulent lawsuits. Nor did I write the manuscript so that it could be used in a scheme to abuse judicial process by engaging in serial fraud on the court.”

When Clancy was notified that I’d contacted Diveroli’s future marks, he fired off a scathing email to me. In it, he stated that by me contacting the defendants’ attorneys, I was only harming any potential future settlement.

What Clancy didn’t mention, however, was that my email had caused a flurry of correspondence between the parties. In fact, the email had been so devastating to Diveroli’s case that on November 5, 2018, Clancy moved to have a scheduled mediation postponed while he scrambled to regroup.

“You’re not gonna believable this,” yelled Pete from across the compound. As he approached, I could see that he was grinning. Pete’s mother had emailed him the court docket. “The email blew up Diveroli’s mediation.”

An immense sense of satisfaction came over me. An image of Clancy and Diveroli sitting in the lawyer’s office, screaming at one another in frustration. Millions of dollars, if not tens of millions had been snatched from their grasp.

Within the hour we had informed Amodeo of the situation. He pondered the news for a few seconds and mumbled, “That was a crippling blow to their case. It wouldn’t surprise me if they settled the lawsuit within the month.”

“What do you think he’ll get?” asked Pete.

“A few hundred thousand,” replied Amodeo, “if that.”

ON NOVEMBER 30, AN ORDER WAS ISSUED by the court indicating that Simon & Schuster, Google, NBCUniversal, Apple, Amazon.com, Rolling Stone, Guy Lawson, Hulu, and CNBC LLC, had settled with Diveroli.

I later discovered that Diveroli’s multi-million dollar lawsuit had been damaged to such a degree that he was forced to accept a fraction of what he was demanding.

THE NIGHT BEFORE I LEFT for the halfway house, Pete and I walked the compound. Inmates that I’d been friendly with were wishing me luck and telling me to stay out of trouble. Typical prisoner farewells.

“Once you get situated,” Pete said, “start calling intellectual property attorneys. It’s not going to be easy.” Unlike personal injury cases—which on average are settled in less than 18 months—intellectual property cases take in excess of five years to reach a conclusion. As a result, IP attorneys don’t take cases on contingency. They simply can’t afford to defer their fee and costs for years in the hope of a positive verdict. “It’s the primary reason that these big studios get away with stealing artists IP; guys like you can’t afford to pay for an attorney to fight them.”

“I know Pete.”

Pete went on and on about the strength of my case, but all I could think about was how much I was going to miss him. “It’s gonna take a ton of calls,” he grinned at me and continued, “but you’re a con man… you’ll find someone.”

TWO PAIR OF SWEATPANTS and four t-shirts was all I had when I arrived at the Tampa halfway house.

Within a few days, I began calling intellectual property attorneys in Tampa and Miami; dozens of them. All wanted $50,000 retainers.

I ended up speaking Francis Malofiy, an attorney that Philadelphia magazine described as a rash, chain-smoking-punk rocker, nontraditional attorney with a switchblade-sharp legal mind.

Fran’s firm had successfully sued multiple hip-hop artists, including Usher, and he’d just won one a $44 million verdict—one of the largest in Pennsylvania history—over the song Bad Girl. In fact, Fran was in the middle of a protracted legal battle with Led Zeppelin over their alleged theft of Stairway to Heaven.

Initially, Fran wasn’t interested in taking the case on contingency. “You’ve gotta give me something,” he said. “I can’t go to trial without a retainer.”

“The government took all my money,” I replied. “Besides, this isn’t going to trial; Diveroli wants to settle. It’s a slam dunk.”

Fran was overwhelmed with cases, so he handed me off to A.J. Fluehr, an associate at the firm. A.J. was extremely knowledgeable regarding intellectual property law and, as opposed to Fran, he radiated business professional. This was a guy that you trusted to do your taxes.

Two days later, A.J. called me and said that he would take the case. “I’ll be counsel of record. Fran can assist.”

THE HALFWAY HOUSE RELEASED ME after seven months. I’d managed to buy an old beat-to-shit Jeep Liberty, but not enough for my own place. I ended up renting a friend’s spare room.

“WE HAVE A MEDIATION SCHEDULED in Miami,” Fran said, during a call in earlier September. “Clancy [Diveroli’s attorney] wants to do it on the twelfth.”

“It’s a four hour drive both ways,” I squawked. “My Jeep will never make that drive.”

MIAMI’S BRICKELL DISTRICT is packed with stylish contemporary skyscrapers and GQ-style businessmen and women. It’s the Manhattan of the south with better weather.

I met Fran and A.J.—the rockstar and his bookish assistant—at One Biscayne Tower. We sat around the conference table, Diveroli’s attorney, Clancy, had all of the charm of an entitled frat boy.

I’m prohibited from disclosing exactly what was said, however, I can tell you that there was no significant movement in either parties’ demand.

I was just leaving Miami’s city limits when I received a call from A.J. requesting I turn around and meet them at the Pink Pony.

“That’s a strip club,” I asked, “isn’t it?”

“Clancy called,” he explained. “Diveroli wants to talk.”

By the time I stepped into the club—around ten o’clock—Fran was working on a solid buzz. He and A.J. were seated at the bar which hugged the large circular stage in the center of the club. Fran was surrounded by several strippers.

Diveroli and Clancy were on their way to the club. In typical Diveroli form, he was late. Over the next hour, Fran went from shoving twenties into the dancers’ lacey garter belts and stockings, to spanking the girls two at a time. When Diveroli and Clancy arrived, the club’s manager, a couple of the security guards, and A.J. were walking Fran to a cab.

As they were leaving, A.J. told Diveroli and Clancy that the meeting wasn’t going to happen, but they didn’t leave. I quickly finished my soda and headed to the exit. Diveroli stopped me halfway across the room.

“Two minutes,” he plead. “That’s all I need.”

We sat at a small table as Clancy watched from a distance. Encircled by a sea of strippers and customers.

“I have a four hour drive back to Tampa,” I yelled over the music. “So, if you have something to say, say it.”

The first thing Diveroli wanted to make clear was that my intervention in the lawsuit “cost me tens of millions.”

“All you and Ross [Reback] had to do was pay me what was owed to me, but you two couldn’t do that.” I reminded him that he had never intended to pay me, specifically because he believed that I wouldn’t be getting out of prison until the year 2030. I chuckled at the thought of it, shot him an evil grin, and snickered, “Bet you never thought you’d see me again?”

Diveroli’s lips tightened faintly. In irritation, he explained that the stress of my intervention had caused Reback’s heart attack. “We were looking at a forty million dollar payday and you fucked it up.” Diveroli leaned into me and hissed, “You might as well have stuck a Glock to his chest and pulled the trigger.”

“You can’t be serious,” I gasped. “You think I’m gonna feel bad for the guy who was trying to fuck me over?” I held Diveroli’s gaze and growled, “Guilt is what killed him, not me.”

Diveroli sneered in disgust, but I knew it was an act. He stared at me for a few seconds. The tension in him subsided and I recognized that he was changing tactics. Diveroli softened, leaned in closer, and confided that he missed talking with me. He missed our friendship—as if our friendship had been real. The ploy was so obviously self-serving, I grinned at the clumsiness of his attempt.

Diveroli confided that—just as Pete and I had ruined his case against Warner—my email to Simon & Schuster, Google, NBCUniversal, Apple, Amazon.com, Rolling Stone, Guy Lawson, Hulu, and CNBC LLC’s attorneys had devastated that case as well. “Probably cost me a twenty million dollar settlement.”

I grinned at him. “Imagine what I could have done if I hadn’t been locked up.” I was after all, at an extreme disadvantage.

“So, how’d you get this lawyer,” he asked. Diveroli knew that I couldn’t afford an attorney like Fran. “What’s he costing you?”

“He hasn’t cost me a dime. He’s so confident in the case, I got him on contingency.” I then rattled off Fran’s many accomplishments. “The guy’s a beast.”

“Why are you getting all in your feelings about this?” spat Diveroli. “It’s not personal, it’s business.” Having written his memoir, I knew that Diveroli never felt good about a business deal unless the other guy got screwed.

“That’s the problem, Efraim,” I replied. “For me, it is personal.” I explained that prison had fundamentally changed my belief system. It had shown me that money was not the singular path to happiness. The experience had given me a purpose. “I was happier in prison writing those stories than I’ve ever been in my life; and you stole that from me. You and Ross took the only honest thing I’ve ever done and you turned it into a fucking scam.”

He blurted out, “Do you have any fucking idea of how much money your lawsuit has cost me in legal fees alone?” He gave me the once over and sneered. “Do you really think I’m going to hand over millions of dollars to you?”

“You know what I’ve spent so far; about two hundred mackerel.” Diveroli winced at the thought that I had conducted a protracted legal battle from prison for the equivalent of $200. I explained that Pete—a drug dealer incarcerated for the murder of two FBI informants—and his associates, a disbarred attorney had helped me fight the case free of charge. “The only person I paid was the guy making the copies for me.”

“You cost me over a hundred thousand dollars—”

“I’m resourceful,” I replied. “You understand, it’s not about the money, right? I live in a rooming house for next to nothing.” I told Diveroli that I had nothing and even if I ended up winning, it wouldn’t change anything for me. “Even if I end up with a few million, it won’t change anything. A bigger place to live and a nicer car won’t change anything. I’m already happy. I’m able to write every day and I’m happy.”

“Then why sue me?”

“Because I know the money means everything to you.” Diveroli and Reback could have lived up to their obligations to me by actively attempting to have the book published and the life rights sold. They could have worked with the multiple production companies that wanted to produce a documentary based on Once a Gun Runner. But they chose to simply use the book as a means to manufacture lawsuits. “In the process, you two greedy fuckers cut my throat.”

“Bro, it wasn’t personal!”

“It’s about to be,” I spat back. “It turns my stomach that you made money off of this perversion.” I pointed toward the door that A.J. and Fran had walked out of and said, “I’m willing to spend every last fuckingdime of Frances Malofiy’s money to ensure that you make as little as possible off of this lawsuit!”

Repulsed, Diveroli withdrew slightly. No doubt, the idea that the money meant nothing to me sickened him. My only concern being to strip him of as much of his illicit gains as I could, through any means at my disposal.

The former-gunrunner began blurting out numbers. When he got to an amount that I was okay with, I stood abruptly and walked out of the club.

I can’t tell you precisely what the final settlement came to, however, I can say that Diveroli was miserable that he had to part with the cash.

MONTHS AFTER I DEPOSITED DIVEROLI’S check, Pete called from prison. “What are you working on?”

“I just finished, It’s Insanity,” I replied. The story is based on Frank Amodeo’s case and I was in the process of self-publishing the book.

I then explained that I’d been thinking more and more about the events surrounding the Dude, Where’s My Hand-Grenade? lawsuit as the case had become known between Pete and I. “It’s kind of interesting, if you think about it. The characters involved, Jonah Hill, Bradley Cooper, Todd Phillips… Warner Brother’s. It’s a great fuckin’ story; the scheme, the players, the marks, the double-crosses…”

“It’s not bad,” Pete admitted. “But it’s no War Dogs.“