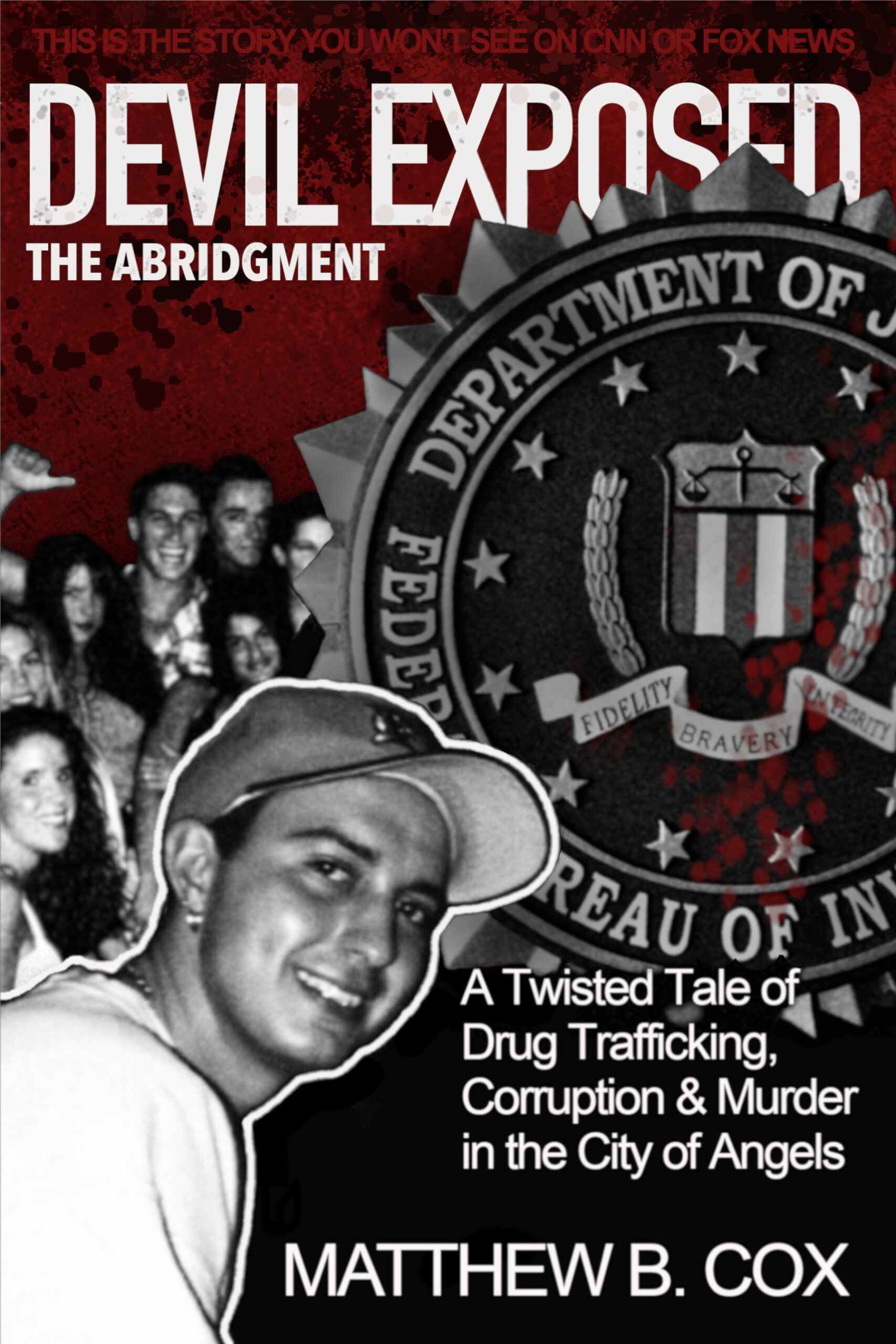

By Matthew B. Cox

ALL FOUR TIRES OF THE PORSCHE caught air as the vehicle shot out of the building’s underground garage. The fire alarm screamed in the distance. The ice lab — located on the top floor of the Sunset Plaza condominium building — was burning. The European supercar hit the asphalt with a thud, Pierre Rausini yanked the steering wheel to the left, and fishtailed onto Sunset Boulevard. The Louis Vuitton duffel bag, containing over half a million dollars in cash, slipped off of the passenger’s seat and onto the floorboard. Rausini whipped by the fire department’s trucks and the Porsche roared down boulevard.

Once inside, the firemen not only discovered a lab, product, and money, they also recovered Jon Ellenberger’s California driver’s license, Joey Escoboza’s personal effects, and Rausini’s laptop. In short order, the LAPD discovered that Joey’s name was on the lease and that the utilities were in the name of Jason Parham.

That night the discovery of the lab was on the local news. The following day, Rausini, Ellenberger, Joey, and Jessie Velasquez — the Sinaloa Cartel’s operative who supplied the raw methamphetamine used to produce the ice — met at the Fashion Island mall in Newport Beach. Everyone was freaking out and no one knew what to do.

Rausini had already begun making arrangements with an attorney to turn himself in when Ellenberger instructed him to call Mark Farchione. Specifically, to see if the crooked FBI agent had heard anything about the lab.

“What the fuck are you guys doing!” Farchione blurted out of the payphone’s receiver. “Are you fucking crazy?” Farcione and his partner Shawn Barreiro — an agent with the FBI’s Organized Crime Drug Enforcement Task Force — were corrupt agents. Farchione growled, “You’re in a lot of trouble.”

Sensing an opportunity, Rausini said, “However much trouble I may be in, pales in comparison to how much trouble you and Shawn are in.” He told Farchione that if he, Ellenberger, Joey, Arya Nakhiavani, or Jason Perham were charged, arrested or even questioned about the lab, “I’ll drop a dime on you and Shawn so fuckin’ fast your heads will spin. If I’m going to prison, I’m taking you thieving bastards with me.”

After a long silence, Farchione said, “We’ll take care of it.” One week later, he told Rausini, “It’s all clear. We tanked the investigation.” According to Farchione, Barreiro had ordered LAPD to “stand down.”

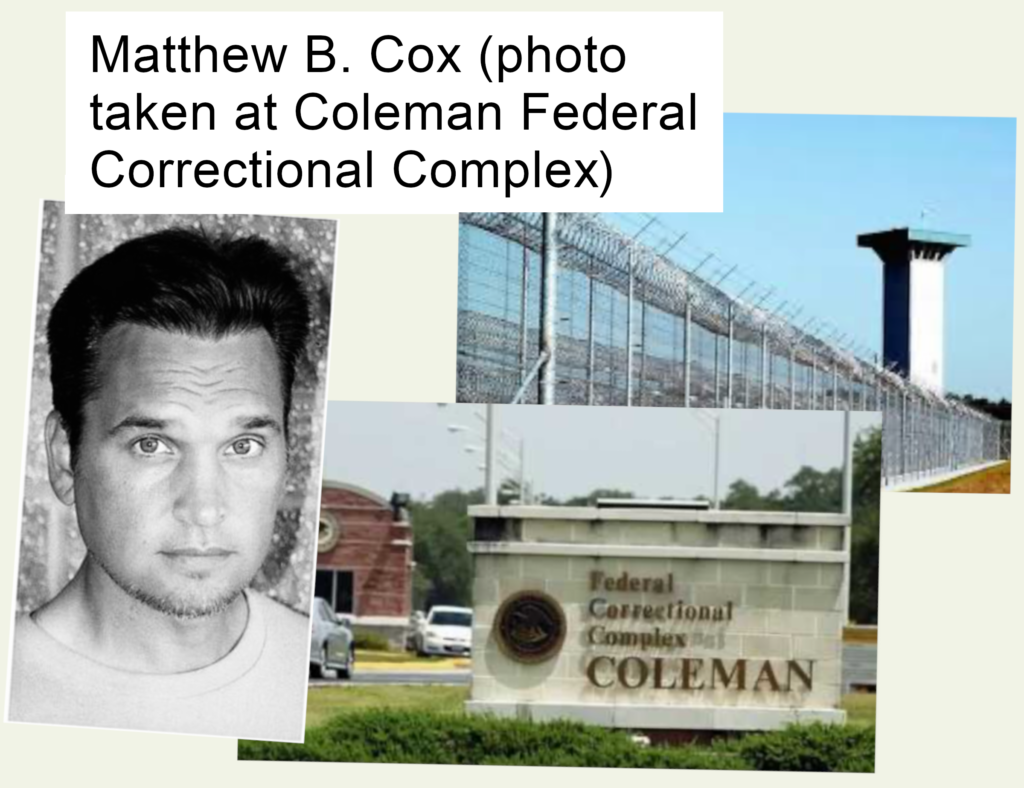

MY NAME IS MATTHEW COX and I’m a true crime writer. You should know, however, I’m also a prisoner incarcerated at the Coleman Federal Correctional Complex in central Florida — the largest prison complex in the nation. That’s how I became acquainted with Pierre Rausini in October of 2016.

Rausini is thin with a shaved head and all the trappings of a computer geek — wire-rimmed glasses, a quiet demeanor, and articulate speech. Nothing about him indicates he was once a Los Angeles drug kingpin; currently serving a thirty-four year sentence for the murder of two federal informants.

He tells me he didn’t commit the crime that he’s spent the last sixteen years incarcerated for. Rausini tells me he has an overwhelming amount of court records, including all of the sealed documents. The contradicting statements by prosecutors. The lies.

“[The government],” says Rausini, “put me in prison for forty years for ordering the murder of a confidential informant that [they] later discovered someone else had ordered; and for putting a bullet in a second informant’s head, that someone else has admitted to strangling.”

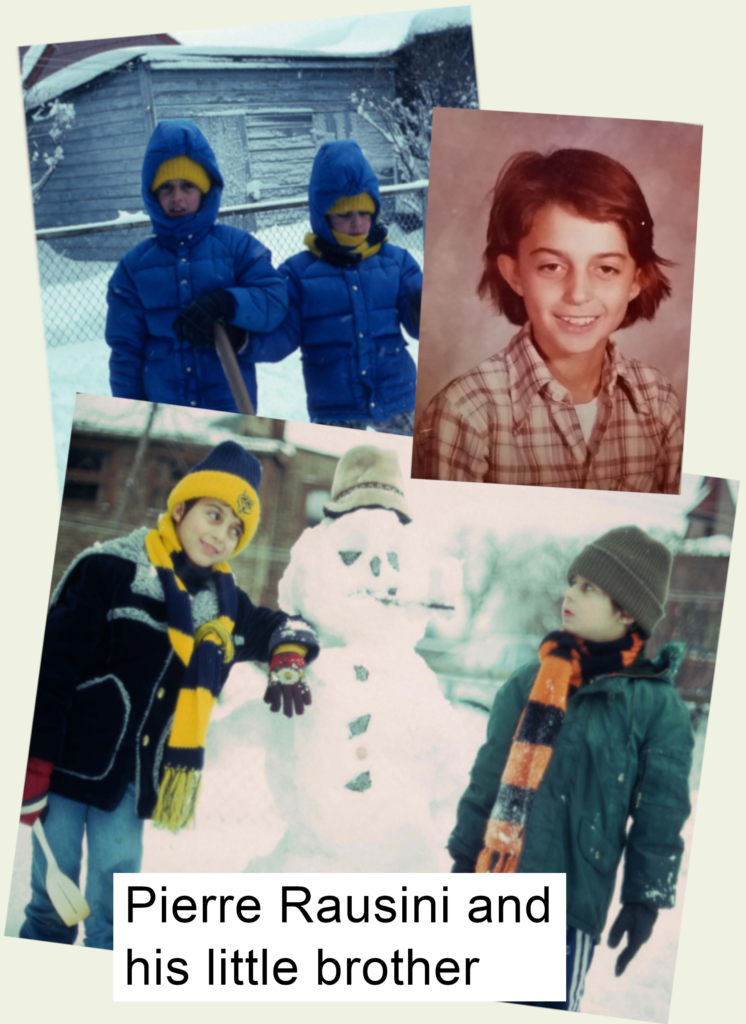

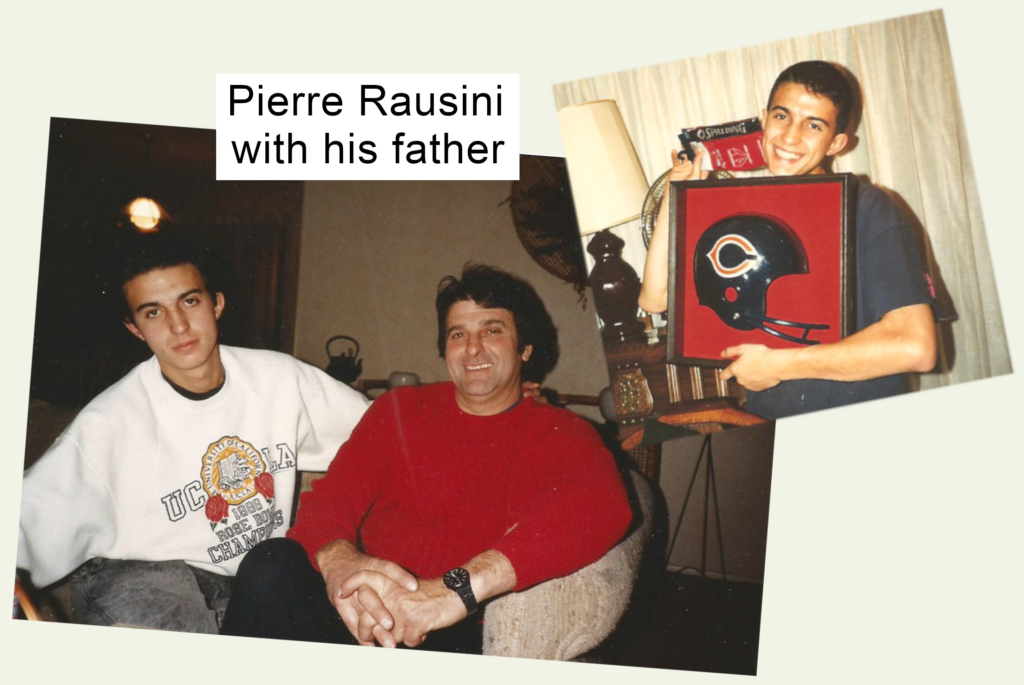

RAUSINI’S PARENTS married in the mid ’60’s. His father was a Brazilian immigrant of Italian descent. His mother, a Latina bookworm. Rausini was born in ’69. He was raised in a home with lots of love and support, although they were not well off financially.

“My father lost his job in 1981,” says Rausini. “As a twelve-year-old, I didn’t have an appreciation of how bad things had become until my parents told me that we were moving to Los Angeles.”

The Rausini’s moved into a small apartment in the City of West Covina, a suburban Los Angeles community, so that he and his brother could attend good public schools.

He found himself in a constant effort to be accepted, to blend in. He wasn’t a big kid and he wasn’t good at sports. He was a computer geek who took Advanced Placement classes and played the piano. He spent most of his time hanging out in the library, programming video games on his home computer or skateboarding.

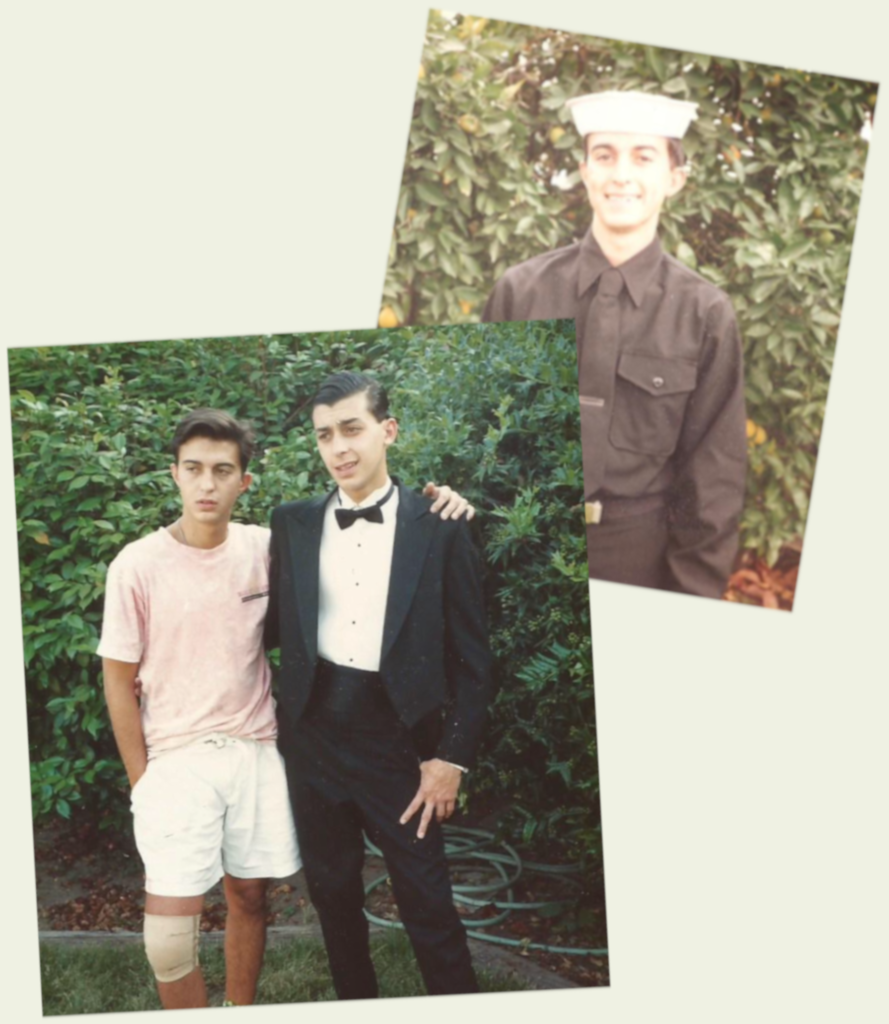

It wasn’t until he entered Covina High School that Rausini built strong friendships. Over the next few years he became friends with Shon Fincher, Robert Sweeny, Kyle Martinez, and Johnny Escoboza, among others.

At the time ecstasy hadn’t been criminalized and teens couldn’t get enough of it. “As far as I was concerned,” recalls Rausini, “ecstasy was the greatest thing ever.”

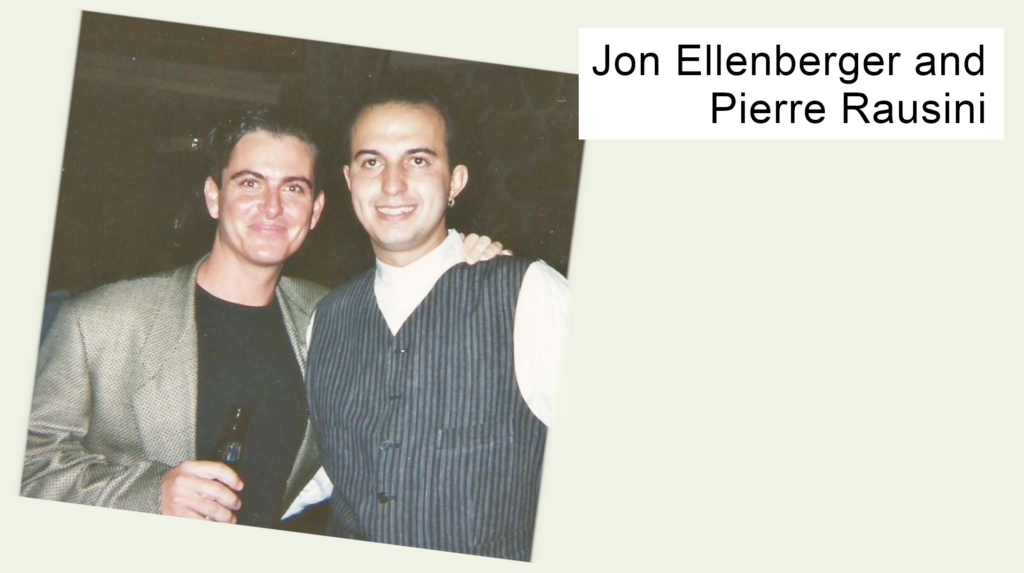

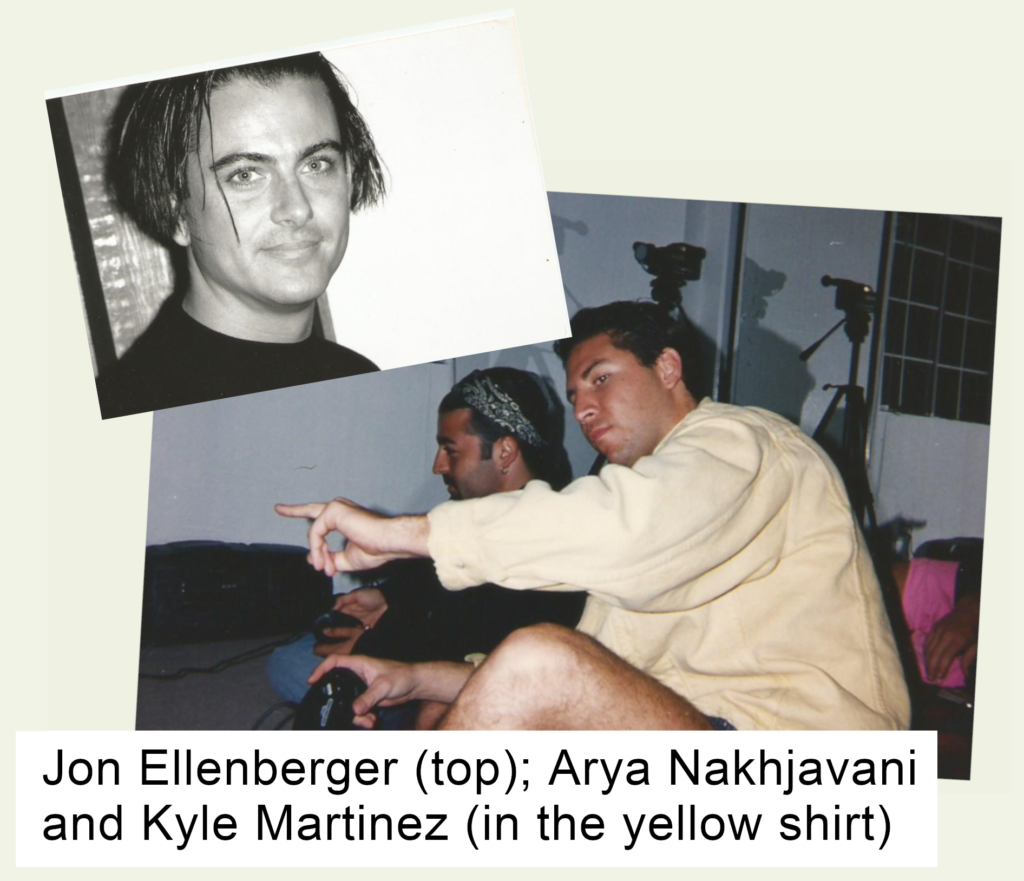

THE FIRST SUBSTANTIAL interaction Rausini had with Jon Ellenberger was in January 1989 at a New Year’s party in Tijuana, Mexico. Ellenberger lived in Newport Beach (Orange County) and had grown up a rich kid. He’d fly to Europe with his Beverly Hills circle to attend ecstasy-fueled parties. The twenty-four-year-old loved the “rave culture” of music, sex and, above all, ecstasy.

“Jon was an elitist,” says Rausini. “He didn’t care if you liked him, but he did want you to envy him.”

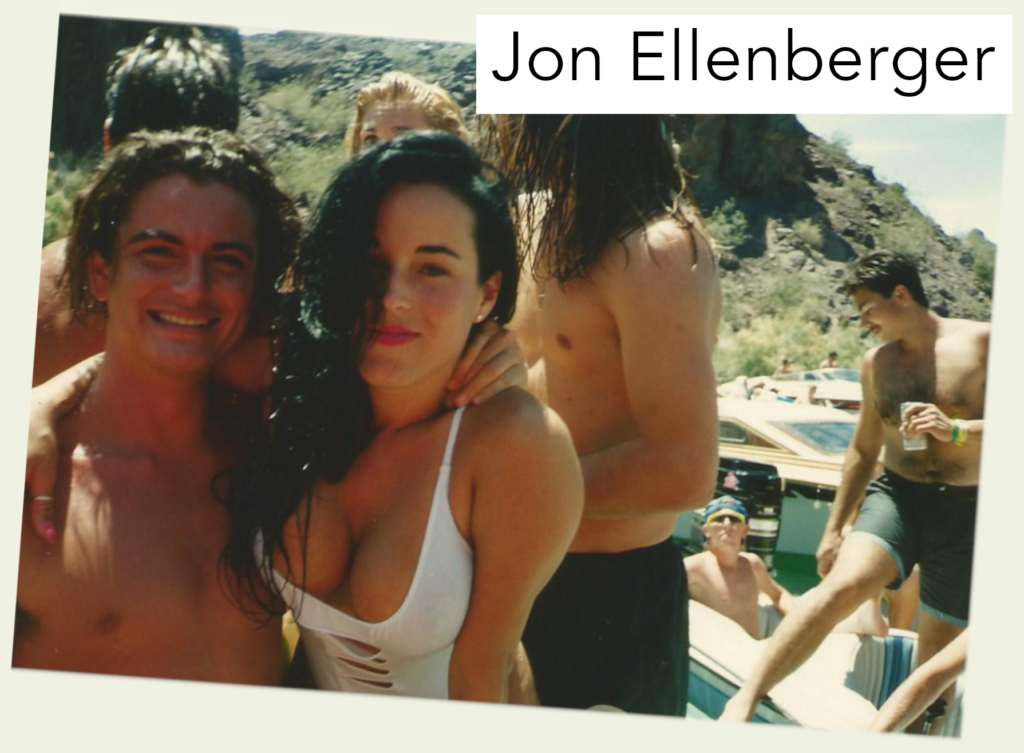

Exceptionally good-looking, Ellenberger showed up at the after-party sporting an over-the-top Playboy model, with his expensive Mercedes parked outside.

The following week, Rausini was with Johnny Escoboza in West Covina when Ellenberger arrived in his Ferrari to pick up Johnny’s older brother, Joey. Rausini turned to Johnny and asked, “Have you ever met anyone like this guy?”

Rausini quickly learned that Ellenberger’s income was derived from cocaine trafficking and that Joey was involved. By that spring, Ellenberger and Joey had also begun dealing ecstasy, which had recently been criminalized.

During the Fourth of July holiday, at a nightclub, Ellenberger pulled Rausini aside and confided, “I’m trying to put together a sales force to hit clubs.” He was currently purchasing ecstasy pills in bulk at $9 per dose; then reselling them for $11 per dose to other wholesalers. Ecstasy, however, was retailing for $20 to $25 per dose. Ellenberger wanted to capture that spread.

“Why me?” asked Rausini. Plenty of his peers would have jumped at the opportunity.

“Cause Joey says you’re the guy that can organize these idiots.” Ellenberger leaned into Rausini and said, “You can pull it off.” Why not, thought Rausini, it’s a harmless party drug.

SPICE WAS A HOLLYWOOD nightclub where the A-list entertainment industry crowd partied. The kind of place where, on any given night, you could find Jon Bon Jovi jamming with Billy Idol in the VIP room with Brian Setzer. One thousand twenty-somethings mixed with movie stars, rock stars, and supermodels.

On the night of October 4, 1989, Rausini approached nearly every pretty girl at Spice, offering to sell them ecstasy. Four hours later, he’d sold over $6,500 — three hundred doses and made himself $1,500.

He then began recruiting friends. Johnny Escoboza, Robert Sweeny, and Shon Fincher. Together — with a half-dozen friends — the boys from West Covina began selling hundreds of doses of ecstasy per night.

By November, however, Rausini had exhausted Ellenberger’s supply. Within a couple weeks Ellenberger met with his supplier, Arya Nakhjavani, an Iranian-American living in the Hollywood Hills, whom he was friends with. Ellenberger obtained additional product. Rausini and his friends began bombarding clubs from Beverly Hills to Newport Beach, distributing thousands of ecstasy tablets. Then, suddenly, Ellenberger’s coffer ran dry, again.

“The supply was becoming an issue,” Rausini tells me. By Spring Break 1990, it was clear Ellenberger had to come up with an alternative source. He knew “a guy” who knew a chemist, Dr. Lester Friedman, a retired University of Southern California chemistry professor. Friedman was willing to develop a formula for the production of pharmaceutical grade MDMA (ecstasy). “That changed everything.”

“WHERE THE FUCK is this guy?!” Ellenberger barked at Rausini. It was early November 1990 and no one had heard from the chemist in days. “You’re supposed to be watching him.”

“How am I supposed to know he was gonna take off?!” Rausini snapped back.

Ellenberger, Rausini, Arya, Joey, Shon, and Robert were standing inside an industrial warehouse next to a stainless-steel rectangular workstation — one of a half dozen outfitted with chemistry racks, stacked with an array of laboratory glassware and reaction vessels. There were rows of fifty-five-gallon drums of chemicals — necessary for the manufacturing of MDMA — and decoy base fertilizer material to keep up appearances.

The precursor chemicals required to manufacture the MDMA compound are highly regulated, and despite Dr. Friedman’s credentials he couldn’t simply order the material. Instead, Ellenberger’s manufacturing team — Friedman, Fincher, and Rausini — developed formulas for the production of each of the precursors from non-regulated compounds.

During that period of time, they had gone from a small lab in a Long Beach business park to a 6,000 square foot facility in the agricultural community of the Inland Empire under the guise of Ditarex Inc. (Latin for “money kings”), a boutique research and development company that specialized in producing custom fertilizers and pesticides.

Finally, after several months of trial and error, they had developed the ability to produce pharmaceutical grade MDMA. The team was on their way to achieving their goal of manufacturing tens of thousands of doses per month — millions of dollars’ worth of ecstasy was within their grasp.

Unfortunately, during the arduous journey, the team discovered that Dr. Friedman, a tall, thin, bald man in his early-sixties was addicted to freebase cocaine.

Due to the numerous delays in reverse-engineering the manufacturing process, coupled with Friedman’s disappearing acts, Ellenberger had grown to despise the chemist.

Hours later, Friedman paged Rausini. However, when Rausini called the number, the individual that answered told him, “I gotcha man here.” Friedman and his girlfriend had smoked nearly $12,000 worth of some dealer’s cocaine. “You wanna see ‘im again, you gotta get me dat bred.”

Ellenberger and Shon dropped off the money and picked up the chemist. The subsequent meeting instantly erupted into a shouting match between Ellenberger and Friedman with Rausini caught in the middle.

“You old fucking crack-head!” spat Ellenberger. “You work for me!”

“It’s not crack, it’s freebase — you ignorant fool!” Friedman screamed back. He turned to Rausini and said, “I refuse to work under these conditions!” and the chemist stormed off mumbling something about being “personal friends with Timothy Leary (one of the founders of the LSD movement in the ’60’s).”

Rausini had watched the same scene play out over and over again. The next morning, the chemist was back at the lab with Rausini and the team.

“Within months,” says Rausini, “the lab was churning out product and everyone was making money.” Ellenberger moved into a spacious house in Beverly Hills. Rausini was driving a new five-series BMW; living in Beverly Hills and dating a beautiful new girlfriend. And because of their pharmaceutical grade ecstasy, they became known throughout the higher level trafficking community.

SHAWN BARREIRO was a Special Agent with the California Bureau of Narcotics Enforcement (BNE). He was cross-designated by the FBI as a Special Federal Officer and assigned to the Organized Crime Drug Enforcement Task Force (OCDETF) in Northern California. The investigations conducted by federal OCDETF units target major drug trafficking organizations. Barreiro, specialized in operating in an undercover capacity — posing as a large-scale cocaine trafficker out of San Francisco. His primary asset was Mark Farchione, a professional BNE informant — a lean, long haired, Harley Davidson aficionado — who partied with porn stars and maintained ties with the Bay Area’s chapters of the Hells Angels Motorcycle Club.

Despite their agent, asset roles, Barreiro and Farchione’s main focus was on ripping off drug dealers. In fact, Farchione was so immersed in the endeavor, he was known to impersonate an agent, complete with an FBI badge credntials, and weapon. For all intents and purposes, Farchione and Barreiro were “partners.”

Ellenberger developed an affinity for Barreiro’s informant that summer because of their mutual passion for Harley Davidson motorcycles.

Around this same time period, Ellenberger was approached by a member of Hells Angels in Southern California. The outlaw motorcycle club wanted to have ephedrine manufactured into methamphetamine in exchange for supplying one of the compounds required to manufacture ecstasy.

Rausini and Friedman spent a couple days in the UCLA chemistry library researching the manufacturing process. The Hells Angels provided Ellenberger with fifty-five pounds of ephedrine. Under the tutelage of the chemist, Ellenberger’s manufacturing team was able to achieve a ninety-plus percent yield — producing pharmaceutical grade methamphetamine.

“It was so pure it was blinding white,” says Rausini. “The Hells Angels were used to the more common peanut butter hue associated with lower quality product saturated with impurities; they accused us of cutting it with inositol.” Following the second extraction, Rausini and Friedman added brown food coloring to meet their expectations. “It was still ninety-nine percent pure, but kind of tannish brown,” Rausini laughs. “The problem was that Ellenberger now wanted to start manufacturing meth, in addition to making ecstasy and distributing cocaine.”

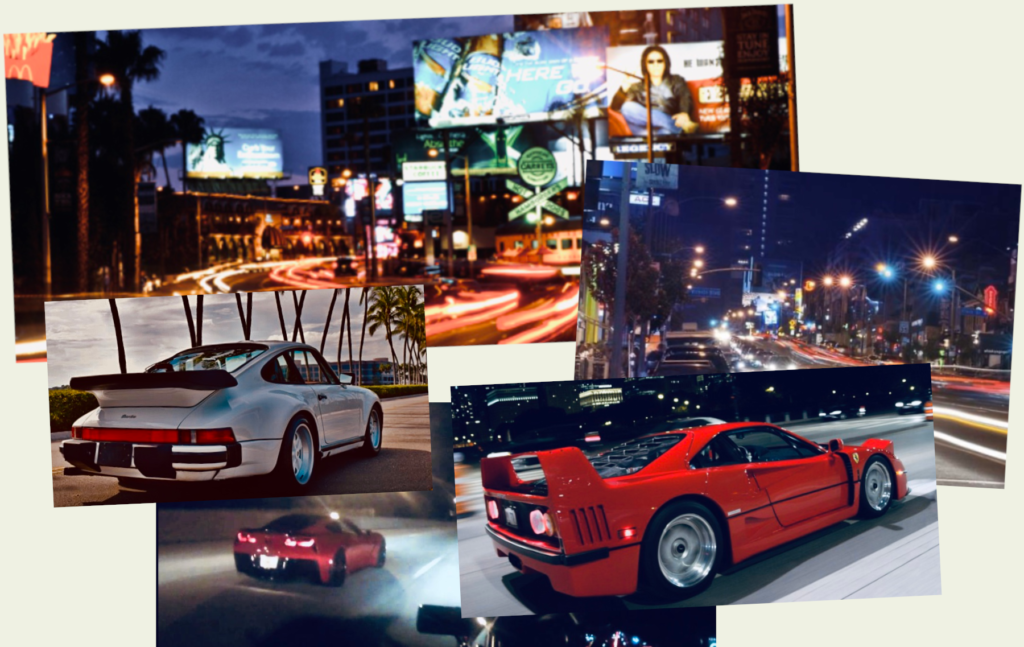

THE TWO FERRARIS BLEW by Rausini so quickly the rush of air rocked his new BMW. Less than a second later, Jay Grdina’s Porsche 930 shot by him. The three super-cars swerved to the left as they raced down Sunset Boulevard through the heart of Beverly Hills.

Between September and December, the lab produced over thirty kilos of ecstasy with a wholesale value of nearly $3 million. The money had amplified everything — the parties, the vehicles, the women — and things were getting out of control.

It was December 7, 1991, the night after Ellenberger’s twenty-seventh birthday. Ellenberger, Arya, Farchione, and Joey had been out clubbing at Bar One in Beverly Hills with a half-dozen of the West Covina guys when Rausini called it a night. Shortly after he’d left the club in his newest BMW — a conspicuous black seven-series — Ellenberger challenged Farchione and Jay to a race down “The Strip.” Ellenberger’s black Ferrari was in the lead as the tightly packed vehicles made a slight right and a sharp left as Sunset snaked through luxury homes and palm trees.

The informant was becoming a fixture among Ellenberger’s circle. Still, Rausini didn’t trust him. He wasn’t from West Covina and they didn’t know a thing about him. Farchione’s presence was unnerving.

Just before Christmas, Ellenberger and the chemist got into another argument. This time it was over money. As a result, while Ellenberger, Arya, Farchione, and Joey were celebrating New Years in Beverly Hills, Friedman cleaned out the entire lab — including all of the customized equipment and fifteen kilos of ecstasy (120,000 doses).

WITH THE CHEMIST holding the lab equipment and the remaining product hostage, Rausini began obtaining ecstasy from Arya Nakhjavani through Ellenberger. He distributed the product to his network of wholesale customers in Phoenix, Chicago, Seattle, and Miami.

Ellenberger was under investigation by the Los Angeles Sheriff’s Department, however, they hadn’t arrested him. Compounding Ellenberger’s problems, a federal OCDETF investigation into Ellenberger’s cocaine activity had been launched. Meanwhile, the DEA was investigating Ellenberger’s methamphetamine trafficking in connection with the Hells Angels.

“Ellenberger was under so much surveillance, by so many different agencies, the street in front of his house looked like a parking lot,” laughs Rausini. “And he was still dealing.”

Regardless of their multiple federal investigations in Los Angeles, Phoenix, and Chicago — Rausini and Ellenberger continued to go out clubbing in Beverly Hills, attended the Midsummer Night’s Dream party at the Playboy Mansion, partied backstage at the MTV Music Awards, and caught every major concert in Los Angeles. Rausini was driving a Porsche 911 turbo and dating a hot stripper.

At a barbeque that summer — with Ellenberger, Arya, Farchione, Joey and a couple dozen other guests — Rausini was introduced to Tim Robles. “Robles was a very serious cocaine trafficker,” says Rausini. “He’d recently been released from federal prison and was looking to re-enter the business in a big way.”

RAUSINI WAS SITTING at a formica table at a Burger King in Hollywood on November 8, 1992. Ellenberger was pitching the idea of supplying Robles with cocaine, when Robles placed a Tic Tac container on the surface of the table, and slid it to Ellenberger.

“Can you make this?” asked Robles.

Ellenberger could see a single crystal shard through the clear plastic casing. “What is it?”

“It’s a crystal,” he replied. “They call it ice, and it’s a fucking goldmine.”

Ellenberger handed the clear plastic container to Rausini, who held it up to the light. He examined the crystal and said, “Yeah, we can make this — provided you supply the raw material or the chemicals to manufacture it.”

Within weeks of that meeting, Rausini, Robert, and Shon got a condo in the same luxury high-rise building located at the base of the Hollywood Hills where Ellenberger and Arya were now living. With their training under Dr. Friedman, they were able to convert pounds of methamphetamine into ice, and achieve one hundred percent purity levels.

“By June, Ellenberger, Joey, Shon, Robert, and Kyle Martinez (another one of Rausini’s best friends from high school) were rocking and rolling,” says Rausini. Ellenberger was trafficking cocaine and converting methamphetamine into ice. Arya and Robles were distributing the product. “The money was obscene. Ellenberger alone was making half a million a month.”

He began making weekly trips to Las Vegas, his gambling was out of control and — despite being engaged to Jenni Breybrooks — Ellenberger was juggling other women on the side.

Joey Escoboza leased a penthouse in an iconic multi-story condominium tower on Sunset Plaza Drive. Rock stars and other celebrities lived in the building, including a couple of the cast from the series Beverly Hills 90210. Ellenberger assembled a new conversion lab and began producing the next load: more than one hundred pounds of ice, worth over three million dollars.

While Ellenberger was producing the ice, Robles needed to obtain an additional fifty kilos of cocaine. Ellenberger reached out to Farchione whom, much to his surprise, agreed to supply Robles with the product on a consignment basis. After operating in an undercover capacity for twenty-two months, Barreiro and Farchione’s moment had finally arrived.

THEY TOSSED THE CASH into a silver Halliburton suitcase. Three hundred thousand dollars of well circulated bills. It was October 19, 1993, Ellenberger and Joey were meeting with Farchione and Barreiro at the Sunset Plaza penthouse. The sole purpose of the meeting was to allow Farchione and Barreiro to inspect Robles’ money which was being used to pay for twenty of the kilos of cocaine. Cash on delivery for twenty kilos; with the remaining thirty being supplied on consignment. The transaction was scheduled to take place the following morning in the building’s subterranean parking garage.

Visible in the living room was over three million dollars’ worth of ice, drying in plain sight of two guys that Rausini had already voiced his distrust of. They weren’t from West Covina.

As Joey turned to place the suitcase in one of the adjacent rooms, Ellenberger said, “You know what; just give it to ’em.” Joey’s gaze ricocheted between Ellenberger and Rausini. Joey replied,

“Tim said not to give them the money until we got his product.”

“That’s my bro, dude.” Ellenberger, motioning toward Farchione. “He’s good.”

Rausini remained silent. The transaction was strictly between Ellenberger, Farchione, Barreiro, and Robles. As such Ellenberger let Farchione and Barreiro walk out of the penthouse with Robles’ cash. An amazingly reckless decision.

The next morning, Ellenberger rode the elevator down to the garage around eleven a.m. to let Farchione, Barreiro, and Curt Scott — another of Barreiro’s professional informants — in to deliver the fifty kilos. He got into Farchione’s white BMW five-series and without explanation the informant — playing FBI agent — handed Ellenberger several manila file-folders.

Ellenberger flipped them open and found Department of Justice reports, as well as surveillance and booking photos of Ellenberger, Robles, and Arya. Farchione pulled out his FBI badge connected to a lanyard around his neck and said, “I love you like a brother, bro, but my partner and I been workin’ this case for two years.” He informed Ellenberger that the building was surrounded. He could see Scott sitting in a Ford dually twenty yards away. “If you don’t come off the product, we’re gonna take you down.”

Ellenberger then called Joey and Rausini and instructed them to pack up all of the remaining ice “and bring it downstairs. There’s a Chrysler Lebaron convertible parked behind the Cafe Med.”

“What’re you talking about — “

“Don’t ask any questions,” said Ellenberger, and he repeated the instructions. They did precisely as they were told.

In plain sight of Farchione, Barreiro, and Scott, Rausini tossed the ice in the back of the convertible. Farchione showed him the DOJ files. The booking photos. The reports. “You come off the product or everyone goes down,” said Farchione. “That’s the deal.” Farchione was upset to learn that they had just missed a fifty-pound shipment that Joey and Rausini had delivered to Robles’ people earlier that morning. Nevertheless, there were still forty-two pounds of ice remaining for Farchione and Barreiro to extort.

Rausini and Ellenberger stood on the sidewalk as Farchione, Barreiro, and Scott drove off with the remaining forty-two pounds of ice. In addition to ripping off $300,000 of Robles’ cash — a total loss of over one-and-a-half million dollars. Keep in mind it was known within the trafficking community that Robles was “good for” several murders. “You may very well catch a slug for this,” Rausini told Ellenberger.

Robles was the largest trafficker of ice on the West Coast by this point, in addition to being a major cocaine trafficker. He was also on federal parole. The FBI, DEA, and BNE all had active investigations targeting him.

“You’ve got me meeting with fuckin’ FBI agents?!” yelled Robles at a meeting several hours later.

“It could have been worse —”

“Shut up! You shut you’re fuckin’ mouth!” spat Robles. Ellenberger didn’t know anything about Farchione or Barreiro. Not their last names, addresses or where any of their associates lived. Nothing. “You vouched for these guys!”

For Ellenberger this was the beginning of the end. Word spread fast that he had vouched for an FBI agent; that he had been “played for a sucker.” Everyone within the higher-level trafficking community began to question Ellenberger’s judgment and some — including a drug trafficker named Lance Estes — had become suspicious that he may have been secretly working as an informant. Rather than maintain a low profile to allow the situation with Robles to blow over, however, Ellenberger began dealing with a couple of Robles’ men behind Robles’ back in response to his vitriolic attacks.

ON DECEMBER 7, 1993, RAUSINI was alone in the lab, burning off solvents in order to extract the remaining product suspended within the chemical solution. Unwittingly, he placed one of the vessels directly underneath a sprinkler head.

A lick of flame escaped into the air and triggered the fire alarm. Suddenly, the building’s system erupted into a massive series of alarms. In a panic, as the fire department screamed toward the building, Rausini grabbed over $650,000 and raced to the building’s elevators.

While firefighters kicked in the penthouse’s door, all four tires of Rausini’s Porsche caught air as the vehicle shot out of the building’s underground garage.

Once inside, the fire department not only discovered a lab, product, and money, they also recovered Ellenberger’s California driver’s license, Joey Escoboza’s personal effects, and Rausini’s laptop. In short order LAPD discovered that Joey’s name was on the lease and that the utilities were in Jason Parham’s name.

That night the discovery of the ice lab was on the local news.

The following day, Rausini, Ellenberger, Joey, and Jessie Velasquez — the Sinaloa Cartel’s operative who supplied the raw methamphetamine used to produce the ice — met at the Food Court at the Fashion Island mall in Newport Beach. The scene was complete chaos. Everyone was freaking out. Ellenberger was still out on bond for the Flanagan burglary. None of them knew what to do. Rausini had already begun making arrangements with an attorney to turn himself in when Ellenberger decided they should call Farchione to see if he’d heard anything about the lab.

Since Rausini was to blame for the predicament, he was told to make the call.

“What the fuck are you guys doing!” Farchione blurted out in a panic. “Why’d you guys go back to that building? Are you fucking crazy?”

Seven weeks earlier, on the day of the purported “reverse-sting,” Barreiro had deceived his superiors into believing that the Sunset Plaza residence had been vacated; that the lab had been moved; and that they had just missed intercepting a multi-million dollar shipment. The whole operation ended with no arrests being made. Now, suddenly, a lab was found. Barreiro had spent the day being grilled by his superiors.

“We gave you a pass,” growled Farchione. “You’re in a lot of trouble.”

Rausini could hear the panic in Farchione’s voice. Sensing an opportunity, he said, “However much trouble I may be in, pales in comparison to how much trouble you and Shawn are in.” He told Farchione that if he, Ellenberger, Joey, Arya, or Jason were charged, arrested or even questioned about the lab, “I’ll drop a dime on you and Shawn so fuckin’ fast your heads will spin. If I’m going to prison, I’m taking you thieving bastards with me.”

After a long silence, Farchione said, “We’ll take care of it.” One week later, he told Rausini, “It’s all clear. We tanked the investigation.” According to Farchione, Barreiro had ordered LAPD to stand down.

“PUT THAT MOTHERFUCKER on the phone,” growled Robles out of the receiver. Rausini and Ellenberger were standing at a payphone in Miami and Robles had just found out that Gary Barnard — one of Robles’ customers — had been arrested. As it turned out, Barnard had been supplying ice to one of Robles’ distributors in Honolulu behind Robles’ back. Unfortunately, Barnard had been arrested after his courier had gotten cold feet and turned in nearly one million dollars’ worth of ice, and the DEA had entered the picture.

Worse still, Ellenberger had been dealing with Barnard behind Robles’ back, as a result, much of the ice seized had belonged to Robles. It boils down to this: Ellenberger had just lost another million dollars of Robles’ product. Just a few days after they had dodged a bullet with the Sunset Plaza matter, Robles now had to contend with yet another investigation. “I’m gonna kill ‘im.”

“Alright, now Tim, this isn’t entirely his fault,” lied Rausini. It was one hundred percent Ellenberger’s fault. “He’s in a lot of trouble too.” The Barnard matter was out of Honolulu, making it the fourth federal investigation Ellenberger was embroiled in that year.

“Put that motherfucker on the phone!”

Rausini handed the receiver to Ellenberger and he placed it to his ear. Instantly, Ellenberger winced, then, he slowly placed the receiver in the payphone’s cradle and sighed. “He said, he’s gonna kill me.”

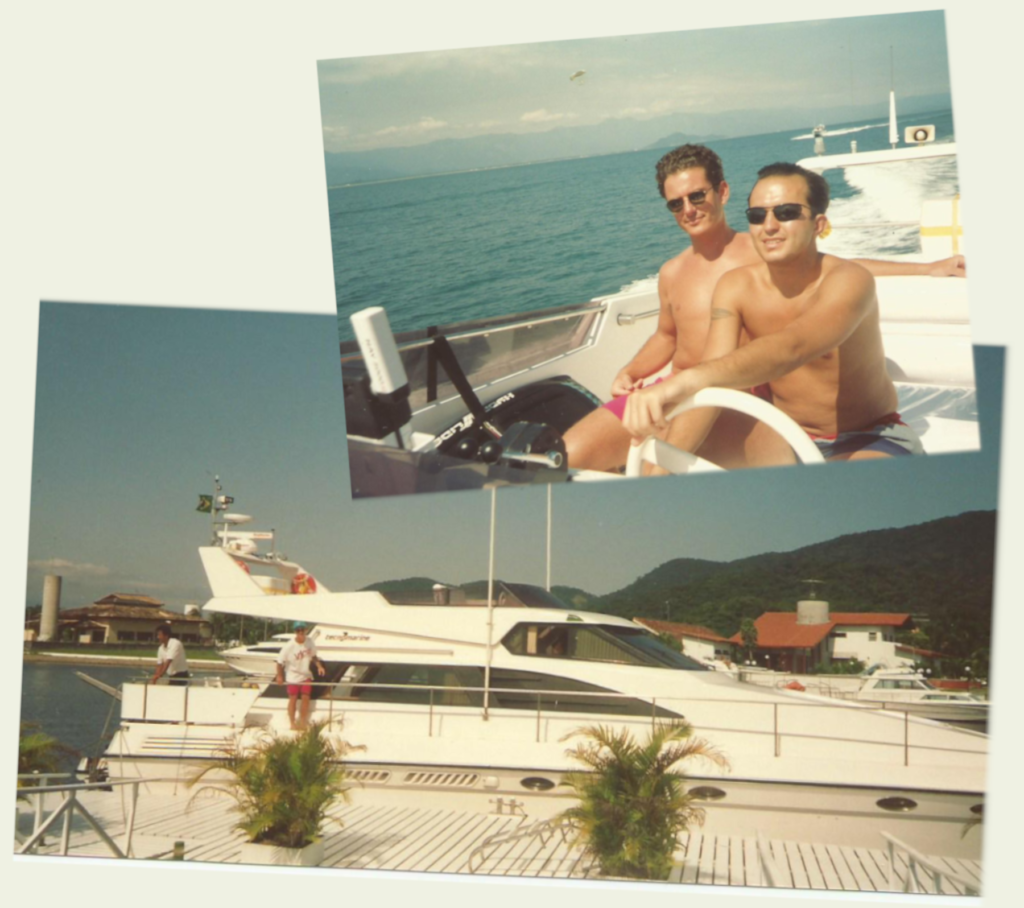

Rausini and Ellenberger spent New Year’s in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, trying to come up with a plan to deal with the “Robles issue.” A month later, things really took a nosedive for Ellenberger.

Arya Nakhjavani, in an act of Shakespearean treachery, told Ellenberger’s fiancée, Jenni Breybrooks, about Ellenberger’s infidelity with numerous women, one of whom he had impregnated. Jenni immediately ended their four-year relationship. With Ellenberger out of the country, Arya was free to seduce his girl. While Ellenberger suspected several individuals of betraying him, he never once suspected Arya.

After Farchione sent word that the Barnard investigation had stalled, Ellenberger immediately returned to Beverly Hills. He stepped out of the breezeway into the terminal at LAX in early March 1994. Despite Robles’ threat he was desperate to salvage his relationship with Jenni. Over the next few months Ellenberger tried everything he could think of to repair the relationship, but nothing worked. Keep in mind, unbeknownst to Ellenberger, Arya was now sleeping with Jenni.

Ellenberger had caused so many problems within the higher level trafficking community, no one wanted to deal with him. And, as a result of Barnard’s arrest, Lance Estes, a fellow drug trafficker, was openly calling Ellenberger an FBI informant. Ellenberger went from dealing with A-level cartel traffickers to obtaining product from second-rate dealers such as John Alonso and Ken Boogren. Over the next seven months Ellenberger’s circumstances continued to deteriorate to the point where he had to sell off his vehicles to pay his gambling debts.

ELLENBERGER TURNED TO JOEY Escoboza, who had underworld contacts, and by November he was back in business converting meth into ice. By this point Gary Barnard — who had not yet been charged for the million dollars’ worth of product seized in Orange County ten months earlier — had been released from federal prison after serving a parole violation. Barnard had yet to be screwed over by Ellenberger and was therefore willing to resume their trafficking relationship. What neither of them knew, however, was that the FBI had taken over the investigation into the Barnard-related seizure and had folded that matter into the FBI-DEA Strike Force’s investigation targeting Tim Robles’ operation.

By Thanksgiving Ellenberger was supplying pounds of ice to Arya and Barnard.

ARYA’S COUSIN REZA was friends with a male model named Frank Nason. Twenty-one years old, extremely handsome, and charismatic, Nason moved to L.A. to pursue a modeling and acting career. In October 1994, Ellenberger hired him as a glorified errand boy.

“Nason idolized Ellenberger,” Rausini confides, “and in return, Ellenberger took every opportunity to belittle and embarrass him. It was one slight after another.”

THE GRAND OPENING of the Hard Rock Cafe Casino was on March 9, 1995. The resort was teeming with celebrities as well as Vegas royalty: mobsters and drug traffickers. Ellenberger and one of his mob buddies were walking out of the restroom when Ellenberger locked eyes with “FBI Agent” Mark Farchione. The informant and his “partner,” Shawn Barreiro, were at the Hard Rock partying with a couple of porn stars.

The men shared an awkward exchange and, after a couple drinks, Farchione confided in Ellenberger that they were in Sin City operating in an undercover capacity targeting a San Francisco ice trafficker that had moved his operation from the Bay Area to Vegas. Farchione told Ellenberger they needed to come up with some ice to establish their bona fides.

“Can you get us some?” asked Farchione. “Four to eight ounces is all we need.”

Given the multiple investigations into Ellenberger’s drug activity, he surmised that having two crooked agents in his pocket might come in handy. “Sure,” he replied, “I’ll hook you up.”

“HOW MUCH ICE did Ellenberger supply?” I ask Rausini. He tells me that over the ensuing six weeks, Ellenberger supplied Farchione with “a couple of pounds.”

“The ice isn’t important,” he says. “What’s important is Farchione and Barreiro were willing to be bought.” Specifically, the informant and his FBI handler were willing to compromise investigations and identify confidential informants within Ellenberger’s trafficking circle. “It’s not that uncommon.”

BY THAT SPRING Rausini and Boogren had allowed Ellenberger to set up a lab at their Marina del Rey condo. For the next month, Ellenberger’s conversion operation ramped up production. Ellenberger’s only real problem was obtaining enough quality raw material to convert.

On April 25, 1995, Ellenberger and Rausini were at Arya’s apartment in Beverly Hills waiting for a call from a potential supplier. Arya had stepped out and they were on the couch playing a video game when the phone rang. Rausini didn’t answer it; instead he let the answering machine take the call.

A female voice emanated from the speaker and Rausini knew it wasn’t their potential supplier. However, she sounded vaguely familiar. As the soft feminine voice thanked Arya for “an amazing night and, of course, the flowers,” Rausini made the connection. It was Jenni Breybrooks — Ellenberger’s ex-fiancée. He immediately looked at Ellenberger, who was staring at the machine, dumbfounded. Suddenly all of the mysteries associated with their break up made sense. Arya was sleeping with Jenni. A calm came over Ellenberger and he stumbled out of the apartment. They drove around West Los Angeles for a couple of hours as Ellenberger talked about what a fool he’d been.

“I’m gonna kill ‘im,” he declared at one point. However, the next morning he’d decided on a fate much worse, “I’m going to put Arya in Mark (Farchione) and Shawn’s (Barreiro) crosshairs.”

ELLENBERGER, ALONG WITH RAUSINI, met Farchione in Marina del Rey the following week. Farchione broke the news that Gary Barnard was in federal custody. “He’s been arrested; an FBI-DEA Strike Force out of Hawaii have him hemmed up,” he reported. “It’s not good.” Barnard had been indicted for participating in a massive cocaine and ice conspiracy, which included the twenty-two pounds of ice that the courier had turned in eighteen months earlier. It was only a matter of time before the dominos started to fall — all of which led to Ellenberger. Farchione continued, “You’re looking at some serious time.”

“What’s it gonna cost me to get out of this?” retorted Ellenberger.

Farchione agreed to look into it. In less than twenty-four hours, Barreiro called Ellenberger and Rausini; he’d spoken with an FBI agent on the Honolulu task force. “He’s blaming you (Ellenberger) for jump starting a public epidemic. They’ve got some of Robles’ people in federal custody and they’re talking.” Barreiro disclosed that Frank Moon and William Batkin were cooperating. Barnard had yet to cooperate, however, he was facing a potential life sentence. “So, he’ll break soon.”

“Holy shit,” gasped Ellenberger.

“The targets of the investigation,” said Barreiro, “in descending order of importance are: Tim Robles, Jon Ellenberger, John Bowley, Ed Kini, George Robles (Tim’s brother), Anthony Mangamelli, and Lance Estes.”

As Barreiro rattled off the names, Rausini could see desperation envelop Ellenberger. He was officially a principal target of one of the highest priority federal drug investigations on the West Coast and the largest ice investigation ever.

Farchione and Barreiro stopped by the condo a few nights later. Ellenberger paid Farchione $20,000 for the information Barreiro provided. He explained that there was no way to tank the Hawaii investigation. The investigation was simply too big. Barreiro told Ellenberger he should consider cooperating with the authorities, in order to get out in front of the matter.

“What if I set up Robles,” asked Ellenberger; knowing full well that Robles wouldn’t do any business with him. “And what if I threw in Estes and Arya — package deal.” Estes, like Robles, hated Ellenberger and would have nothing to do with him. “I’m taking a big risk here; Robles is good for three or four murders. Tell the Hawaii feds I want immunity if I cooperate —”

“Absolutely not!” snapped Barreiro. “You’re looking at thirty years, if not life. You started a fuckin’ epidemic. You have no choice but to cooperate on their terms.” In that vein, Ellenberger asked Nason — who was unaware of Ellenberger’s plan — to contact Sid Berman, one of Estes’ minions. Ellenberger offered to sell Berman a couple pounds of ice. Days later he purchased that product and, ten days after that — he bought an additional three pounds.

Then, on the evening of May 18, 1995, Rausini met Michelle Vergara out at the Empire Ballroom nightclub. The couple were dancing when he noticed Nason step out of the crowd. He’d just found out that Ellenberger was using him to setup Estes. Drunk and pissed-off, Nason yelled over the music, “I’m gonna kill this motherfucker; I’m gonna beat his ass!”

“Don’t do anything stupid,” Rausini replied. “We’ll talk about it tomorrow.” Rausini laughed off the threat, figuring it was the liquor talking.

Shortly after Nason stumbled off, John Alonso informed Rausini, “Frankie (Nason) just left. He said he’s going to the Marina to deal with Jon (Ellenberger).”

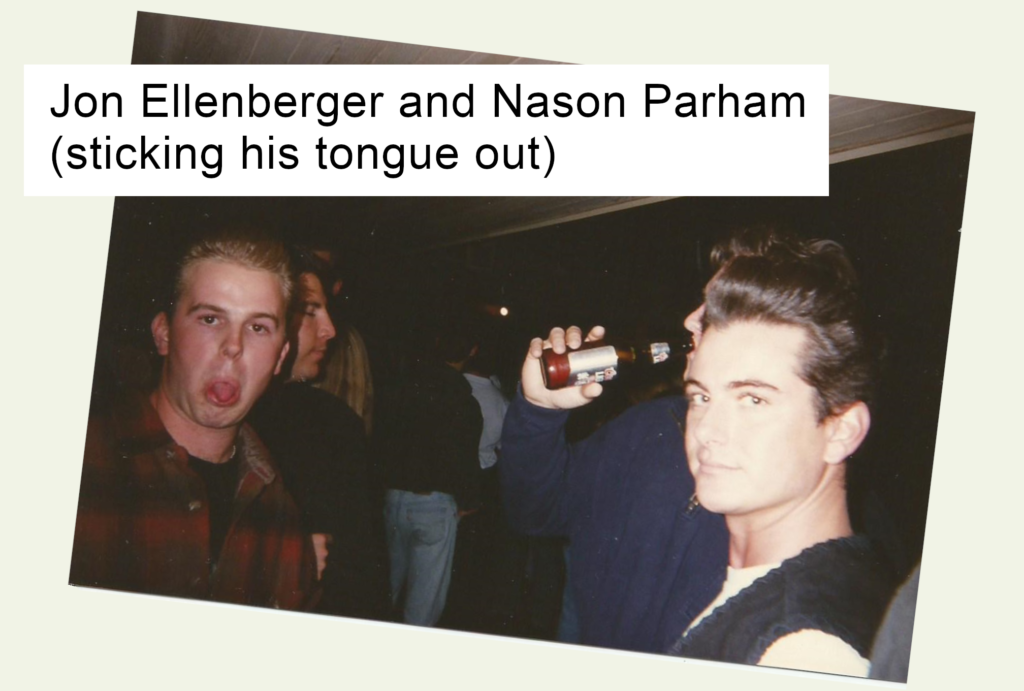

Rausini had Alonso drive him back to the condo. However, when they got there —around one a.m. — Ellenberger was watching cable and Nason was in the bathroom shaving, getting ready to go spend the night with a girlfriend. Everything seemed fine. Rausini got back to the club around 1:45 a.m. Sometime between 2:30 a.m. and 3:30 a.m. — when Nason called Rausini’s hotel room to speak with Alonso — there was a confrontation of some nature, which ended with Nason strangling Ellenberger to death.

“MICHELLE DROVE ME BACK to the Marina the next afternoon — around one p.m.— and waited in the car while I ran in to get a change of clothes,” says Rausini. He and I are in the library and Rausini seems melancholy at the thought of Ellenberger’s homicide. They were friends after all. He found the body lying face down on the floor of the bedroom. Ellenberger’s head rested at an unnatural angle. Twisted and motionless. After determining Ellenberger was dead, Rausini regained his composure. He couldn’t call the police and report there was a dead body in his drug lab. There were a few thousand doses of ecstasy, twenty thousand dollars of cash, and over 100 pounds of ephedrine in a closet filled with laboratory equipment.

Rausini grabbed Ellenberger’s cell phone and paged Farchione — whom he believed was an FBI agent. He then grabbed his money, the ecstasy pills, and his laptop and ran out of the Marina while placing calls to Farchione and Arya’s pagers.

Minutes later he got in contact with Farchione. “Jon’s dead! And I don’t know what to do —”

“Stay cool,” he replied. “Don’t call the cops.”

Rausini met with Nason and he admitted to having killed Ellenberger. According to Nason, they had fought and he’d “choked Ellenberger out.” His hands were scratched and bruised. “He sucker punched me and I snapped his neck.”

By that night Alonso and Rausini had enlisted Wayne Harrison’s help. Harrison was a bookmaker, collections-leg-breaker-thug and occasional cocaine dealer whom Rausini knew through Alonso and Boogren. Rausini met with Harrison in Diamond Bar. For $40,000 Harrison and two of his men — Dean Ziroli and Kelly Davis — wrapped Ellenberger’s body in industrial plastic and a sleeping bag. They disposed of it in South Central Los Angeles. The body was never recovered.

RAUSINI BEGAN HIS DRUG TRAFFICKING relationship with Lance Estes on June 1, 1995. A couple of weeks later, on June 17, 1995, Reza — while acting as a courier for Arya — was arrested at LAX as he boarded a plane bound for Honolulu. He was transporting six pounds of ice.

Rausini contacted Farchione and asked if there was anything he or Barreiro could do to assist Reza. While waiting for their response, Rausini apprised Estes — who had supplied two of the pounds that Reza had been arrested with — of the situation. “I’m trying to get it taken care of,” Rausini confided. He informed Estes that he knew a dirty FBI agent. “Him and his partner are looking into it.”

“The same agents that ripped off Jon (Ellenberger) and Tim (Robles)?”

Less than two months later, Reza was walked out of the Los Angeles county jail.

Unbeknownst to Rausini, Estes and his best friend, Michael Cefalu, had been arrested in San Francisco a few months earlier for trafficking cocaine. Estes, the guy that had spent the previous eighteen months calling Ellenberger a “snitch,” had entered into an agreement with the FBI to cooperate in exchange for time off his prospective sentence. Despite the agreement with the FBI, Estes was continuing to distribute cocaine and ice while pretending to cooperate. “Do you think these agents can do something for me?”

Rausini made a second call, requesting Farchione and Barreiro look into Estes’ case. Farchione told Rausini that Barreiro was close to the undercover agent in San Francisco, Randy Blum — another cross-designated BNE agent assigned to the FBI’s drug task force — and that they could “tank Estes’ case for one hundred thousand dollars and two pounds of ice.”

Estes was in shock. In less than an hour Rausini had been able to obtain specific information about his case, including the identity of the undercover agent who had busted him. While he was contemplating the bribe offer, on June 19, 1995, one of Estes’ distributors, Jeff Meacham, was arrested by the DEA at Maui International Airport. They seized five pounds of ice. What Estes didn’t know was that his best friend, Cefalu, had betrayed him by reporting to the FBI that Estes was still trafficking drugs while pretending to work as an informant. On June 28, 1995, Estes agreed to pay Agents Belleiro and Blum $100,000 to dispose of Estes federal case.

On July 1, 1995, the day before Estes had planned to send Nason to Hawaii with seven pounds of ice, Rausini received a call from Farchione. “Don’t let Estes send the product,” he warned. “It’s a bust. The Hawaiian feds are gonna be waiting on Frankie at the airport. They’re collapsing the Hawaii end of the conspiracy.” Then, on the night that Rausini and Nason dropped off the initial $50,000 payment from Estes, July 8, Farchione explained that Estes was in a “shit load” of trouble. “He’s the target of ‘Operation Avalanche,’ being run by the FBI’s task force out of San Francisco. He entered into a cooperation agreement with their office; then double-crossed them. They’re fully aware he’s been playing them for fools,” said Farchione. “You let him know we’re the only thing keeping him from doin’ twenty years.”

“I understand,” mumbled Rausini.

Tell him to stop all transactions and to keep his mouth shut; there’s an informant in his organization.” The confidential law enforcement information that Estes had entered into a cooperation agreement was then discussed with Harrison, Nason, and Francisco Diaz (one of Estes’ associates).

On July 19, around eleven p.m., Rausini and Estes met Farchione in a parking lot. At the rendezvous, Estes wanted proof Farchione was FBI. In a swift motion, Farchione whipped out a badge connected to a lanyard around his neck and his automatic. He pointed the weapon at the flat of Estes forehead and growled, “I’ll put a fuckin’ bullet in your head right now.” Estes froze. Farchione pulled a second automatic out of his back pocket. “Then I’ll put this piece on you. See my partner over there?” He motioned to a serious looking man standing across the street — he nodded at Estes. “He’s gonna say you reached for the weapon; now stop fuckin’ around.”

“Okay, alright, alright,” gasped Estes. Farchione discussed the cooperation agreement Estes had entered into with the FBI’s task force in San Francisco and identified the names of the agents who had interviewed Estes. Farchione also identified the names of Estes’ associates in Los Angeles and Honolulu whom the FBI and DEA were targeting, including individuals in Honolulu known to Estes, but unknown to Rausini. Farchione had Estes convinced that he was a federal agent.

Estes wanted the name of the FBI’s informant in his organization. Farchione agreed once everything was over, he’d give him the name. One week later, on July 25, Rausini delivered the second $50,000 to Farchione.

However, within days Barriero’s coconspirator, Randy Blum was questioned by the U.S. Attorney’s office regarding allegations of corruption — it turned out that Estes had confided in Cefalu who’d immediately notified the federal prosecutor.

“That motherfucker’s been running his God damn mouth,” yelled Farchione. “You tell him the deal’s off!”

Over the next week, Rausini managed to put the deal back together, however, Farchione and Barreiro wanted an additional $50,000 for the headache Estes had caused. This, in turn, prompted Farchione to instruct Rausini to shut down the lab. Farchione indicated that they were taking Estes down and that “papers were being filed in court” later that week charging Estes with drug trafficking. Rausini told Harrison that Farchione had told him to shut down the production until the matter with Estes could be resolved.

On August 16, 1995, at a meeting between Harrison and Rausini, Harrison told Rausini that he planned on killing Estes. Prior to finding out that Estes was an FBI informant, Harrison had conducted a couple of ice deals selling Estes’ product. Harrison had also conducted a collection for Estes in Orange County and had recently accepted another contract to do a collection in Alaska; an assignment both men understood contemplated the likelihood of someone being harmed. “This motherfucker could’ve been wearing a wire,” growled Harrison. “I’m just gonna kill ‘im.”

“What’re you telling me for?” snapped Rausini. “It’s none of my business.” Harrison was under the false impression that Rausini knew Estes’ address in San Francisco. “I don’t. Besides, the guy supposedly lives with his girlfriend. What if she’s home?”

“She’s gotta go,” said Harrison. Nason recoiled. He was close to Estes. Rausini was indifferent about Estes, but he was strongly opposed to any innocent civilian being harmed.

“No,” he objected. “Look, let me call the agent —”

During that call, Rausini explained Harrison’s plan and asked Farchione to talk to him. To straighten him out. The conversation sparked a meeting, wherein Farchione, Harrison, and Rausini met to discuss, what Rausini thought, was an alternative to killing Estes.

Standing in a gas station’s parking lot, Harrison laid out his case for eliminating Estes. To Rausini’s surprise, Farchione agreed that Estes had to be killed. His only concerns were where the murder should take place, Los Angeles, and to “make sure no one finds the body. We’re better off if he’s considered a fugitive.”

Then, after another one of Estes’ customers had been arrested the week before — this one in Alaska — Estes began to suspect that Cefalu may actually be the informant. That realization caused him to re-evaluate his decision not to pay Farchione and Barreiro. However, it took Rausini and Nason to convince him to take the deal.

“I swear to God,” Farchione relented, “if this motherfucker doesn’t show up with the cash I’m gonna have Wayne (Harrison) put a fuckin’ bullet in ‘im!”

WE’VE GOT EIGHTY-SIXES across the board,” gasped Mrozek, franticly screwing the silencer on the muzzle of his Uzi subcompact assault rifle, as he rushed out of the kitchen. It was August 28, 1995, Rausini and George Mrozek — one of Harrison’s associates — were waiting at Harrison’s beach house in Newport Beach. Harrison and Nason had picked up Estes from the airport, and they were due to arrive any minute. In addition, Rausini had asked Craig Arranaga, an associate, to accompany him due to the volatile atmosphere surrounding the Estes issue.

Unfortunately, 86 was the pager code indicating that Estes had arrived without the cash, and Harrison and Mrozek intended to kill him. Mrozek torqued-down on the silencer and repeated, “We’ve got eighty-sixes.”

“Fuck!” snapped Rausini. He was only at the house because he’d been led to believe the hit had been called off. He and Arranaga hadn’t signed up for a murder. To top it off, the vehicle pulled to the curb outside the house with Estes, before Rausini and Arranaga could even consider leaving.

Instead, Rausini’s stomach wrenched. He got up off the couch, turned to Arranaga and said, “I can’t watch this.”

As Harrison, Nason, and Estes entered the front door, Rausini stepped into the garage. Mrozek was on the back deck pretending to work on Harrison’s Harley. In truth, he was revving the engine to drown out the sound of the gunshot.

Estes followed Nason into the kitchen and Harrison walked in behind them. Nason opened the refrigerator to grab a beer. He leaned over, Harrison whipped out a .25 caliber semi-auto and — at point blank range — fired a single slug into the back of Estes’ skull. His body collapsed to the floor.

When Rausini re-entered the house, Harrison was digging through Estes’ pockets. Rausini stood inside the doorway staring at the lifeless body sprawled out on the tile. In a numb monotone, Rausini asked, “What happened? He said he had the money.”

Harrison thrust his hand in the air with a rectangular piece of paper clenched in his fist. “He brought a fuckin’ check!” Estes had twenty grand in cash and a $30,000 cashier’s check. “A fuckin’ check!” Harrison pocketed the cash and handed Arranaga the firearm to dispose of.

Within minutes, Harrison, Arranaga, and Mrozek wrapped the body in industrial plastic and a sleeping bag. The following night the body was disposed of in a dumpster in Oceanside (San Diego County). Less than twenty-four hours later, a homeless man digging for cans found the remains.

A few days later, on September 1, 1995, the FBI raided Rausini’s parents’ house in connection with federal charges out of Hawaii. The U.S. Attorney’s office in Honolulu had misidentified Pierre Rausini — due to his use of his younger brother’s American Express card — as John Rausini.

The next morning Rausini called his mother to say hello. “What have you done now!” she shrieked. “The FBI arrested your brother!” They had taken him to the Metropolitan Detention Center in Los Angeles.

“Let me make a call.” Rausini contacted Farchione and explained the situation. Barreiro made a few calls and by that afternoon, he’d not only arranged to get Johnny released, he had the FBI drive him home and the lead agent apologize to Rausini’s parents.

That night, Farchione called Rausini. “God damn it!” he yelled. “I thought Wayne said they wouldn’t find the fuckin’ body!” The Oceanside Police Department not only had found Estes’ body, the homicide detectives had identified him. Within days both Agents Barreiro and Blum had spoken with the detectives; who were insisting that they — Barreiro, and Blum — answer some questions.

Farchione met with Harrison, Rausini, and Nason, and they coordinated their stories. Harrison met with Detective Porretta, and gave him the agreed upon narrative. Nason used the pretext of having warrants to refuse to meet with the detectives. As for Rausini, he was told by Barreiro not to speak with the detectives; that all law enforcement inquiries had to go through him because he (Barreiro) was Rausini’s “handler.”

One week later, Rausini was a little drunk when an L.A. Sheriff’s deputy asked for his ID after he’d left a Beverly Hills nightclub. Assuming the feds had cleared his brother’s name, Rausini handed them his brother’s ID, John Rausini. He was arrested for public intoxication.

Once Rausini was in the holding cell — around three a.m. — he called Robbie Macias —one of Rausini’s friends from high school. Robbie knew about Rausini’s relationship with a crooked federal agent. Robbie turned around and called Farchione. Farchione called Barreiro who immediately called the West Hollywood Sheriff’s sub-station and, by 6:30 a.m. — despite having two federal warrants for his arrest — Rausini was released.

“UNTOUCHABLE,” Rausini tells me. “That’s how I felt.” He was convinced that Farchione and Barreiro would get him dropped from the Hawaii and San Francisco indictments as well as cleared of the Estes murder. “It seemed like they could take care of anything with just a couple of calls.”

Then, on January 5, 1996, Rausini was arrested for possession of a false ID while in Newark, New Jersey. Once again, he was booked as John Rausini. However, this time he wasn’t able to get out of the building before he was correctly identified as Pierre Rausini.

THE COVER UP officially began in August 1996, when Special Agent Blum requested a meeting with FBI Agent Bruce Burroughs, the head of the “Operation Avalanche” task force. It’s unclear precisely what sparked the meeting. Nonetheless, it can be inferred that Barreiro and Blum realized they weren’t going to be able to help Rausini and therefore decided to begin covering their tracks. At that meeting, Blum “confessed” that he had nonetheless participated in an unauthorized operation to deceive Estes into believing that a corrupt FBI agent existed, and that Estes could bribe this agent to “make his case go away.”

Blum later changed his story. In October 1996, Burroughs told Detective Porretta that both Agents Barreiro and Blum, as well as Farchione, whom Barreiro had posing as the corrupt FBI agent, had participated in an unauthorized investigation to trick Estes into believing that a corrupt federal agent existed. Burroughs also reported that Blum had admitted to having disseminated confidential law enforcement information to Barreiro — which was passed on to Farchione — so that Farchione could establish his bona fides with Estes. However, instead of informing Burroughs that they’d received $100,000 from Estes and had leaked that Estes was an FBI informant, Blum falsely claimed they had only shared harmless information.

Regardless, Burroughs — the head of the FBI’s San Francisco drug task force — now knew that his agents had been lying to the homicide detectives (thus obstructing the murder investigation) for well over a year, in addition to having participated in an unsanctioned operation which resulted in Estes’ murder. Nonetheless, Burroughs didn’t reprimand Blum or launch an investigation into Barreiro’s activities; instead, he contacted Detective Porretta and glossed over the inaccurate nature of the information Blum and Barreiro had previously provided.

Porretta, however, did not share Burroughs’ non-chalant attitude.

On November 4, 1996, at a hotel in Hollywood, FBI Agent Burroughs, Detective Porretta, and David Hall — one of the prosecutors assigned to Rausini’s case — met with Barreiro and Farchione. The agent and his informant insisted that they did not accept any money from Estes. And that if Estes had paid any money, Rausini must have kept it. Farchione reported that Rausini had confessed to killing both Ellenberger and Estes. According to Farchione and Barreiro, Rausini had murdered both men for fear they would ultimately cooperate against him. Farchione reported that both men had been fatally shot; that Rausini had shot both men; and that Rausini and an associate had buried Ellenberger’s body in the dessert.

No one bothered to ask Farchione or his handler, Barreiro, why neither of them had previously reported that Rausini had confessed to having committed two murders. Nor had they inquired as to why the agent or his informant hadn’t reported Ellenberger’s murder during the preceding eighteen-month period.

By January 1997, Rausini concluded that Farchione and Barreiro had abandoned him. So, he decided to play his trump card and asked his lawyer to contact the U.S. Attorney’s office and offer his cooperation in connection with corrupt law enforcement and the Estes murder.

Unexpectedly, U.S. prosecutor responded, “The only way my office will consider cooperation from Rausini is if he agrees to plea to life.” The subtext being the San Francisco U.S. Attorney’s office wasn’t interested in pursuing corrupt law enforcement. By this point, John Lyons — one of the Assistant U.S. Attorneys on Rausini’s case — Hall, and Burroughs were already actively covering up the FBI task force’s misconduct.

On January 30, 1997, Agent Barreiro appeared before the grand jury. He testified that Ellenberger had agreed to cooperate and was scheduled to sign up as an informant on the very day he disappeared — which was untrue. Moreover, he stated in the Estes matter, he and Farchione had participated in a ruse, to deceive Estes into believing that a corrupt FBI agent existed whom Estes could bribe.

Specifically, the agent testified that “They (Rausini, Estes, Robles, Arya, and Joey) thought that Mr. Farchione had a contact — a contact in Northern California that was a law enforcement contact and that Mr. Farchione had the ability to dispose of charges. “Farchione had indicated that his contact was a DOJ (Department of Justice) agent.”

A couple months earlier, however, Barreiro told Burroughs and Detective Porretta that Farchione had portrayed himself as an FBI agent at his direction. In contrast, Farchione later claimed that, at no time did he ever represent himself as a federal agent. When he appeared before the grand jury on February 6, 1997, he testified that the actions he undertook during the “Operation Avalanche” investigation were at the direction of FBI Agents Barreiro and Blum. And in a moment of unguarded candor, Farchione let slip that he expected the agents to “give me some kind of payment out” of the “one hundred and fifty thousand dollars” Estes was paying to get his case disposed of.

Around the same time period, Farchione learned that Rausini had offered to cooperate. This triggered a flurry of calls and meetings between Farchione and Harrison. The purpose of which was to concoct a story setting Rausini up as the fall guy for the Estes murder in order to deflect attention away from them. This prompted Harrison to hold a series of meetings at his girlfriend, Odalis Melendez’s residence, one of which — in mid-February 1997 — was attended by all of the players: Farchione, Harrison, Arranaga, Alonso, Mrozek, Nason, the two thugs that disposed of Ellenberger’s body — Dean Ziroli and Kelly Davis — as well as unknown men, one of whom was Arya Nakhjavani, whom Harrison’s girlfriend had identified as “John from Beverly Hills.”

Farchione explained that Rausini was “looking to cut a deal” and that they needed to get their stories straight to protect themselves.

While the men held their meeting in the living room, Melendez waited in her bedroom, where she overheard aspects of the conversation taking place. During the course of the meeting, Melendez heard the men concoct a story about Rausini being responsible for killing both men. The final version — concocted under Farchione’s guidance — being that Rausini murdered Estes and Ellenberger by shooting both men.

A few months after the formation of the scheme, the FBI began questioning the conspirators. On July 31, 1997, Farchione was examined by detectives from the LAPD’s elite Robbery Homicide (Special) Division. He held firm to the story that Rausini was responsible for killing both men. He did, however, admit he’d stolen over $100,000 from Ellenberger and Rausini during the Robles investigation. At a subsequent interview conducted by the detectives Farchione claimed that, although Barreiro wasn’t involved in the theft of the $100,000, his FBI handler was aware of the incident.

During the same time period, Arranaga was questioned by the FBI in Los Angeles. He also told them the murder was a spontaneous act and that he had no prior knowledge that Estes was going to be killed; he added, however, that — at Rausini’s direction — he’d purchased the Cannon brand towels that were used to stop the blood flow. At a follow-up interview, on August 6, Arranaga reiterated the same information. He was then given a polygraph, which he promptly failed. He then changed his story, reporting that he knew Rausini was going to kill Estes when he accompanied him to the beach house. Arranaga then failed a second polygraph on August 26, and, once again, he changed his story. This time stating that not only did he know about the murder, but that he disposed of the murder weapon. Arranaga insisted, however, that Rausini was the “actual murderer.”

On September 3, 1997, Arranaga failed a third polygraph. Once again, he altered his story, this time he indicated Harrison committed the murder. In addition to identifying Harrison as the shooter, he claimed Rausini ordered the murder to keep Estes from cooperating. During the interview he expressed his belief that the murder may have had something to do with a crooked agent. Nevertheless, he laid the blame for the murder at Rausini’s feet – a version the FBI found probable.

On October 2, 1997, a Second Superseding Indictment was returned. That indictment charged Rausini with participating in a drug conspiracy to distribute cocaine and methamphetamine and with operating a continuing criminal enterprise. It also alleged Rausini, Harrison, Nason, and Mrozek killed Estes to prevent him from cooperating and that Rausini killed Ellenberger during the narcotics conspiracy.

Following his arrest, on October 8, FBI agents questioned Mrozek. During his interview, he indicated he could not identify the person who shot Estes. He also claimed that Rausini had stated that the victim was an informant, and he saw Rausini leave with the murder weapon. Prior to his next interview, however, Mrozek was given a polygraph, which he failed. Thereafter, Mrozek changed his story. This time, he claimed that Rausini was responsible for killing Estes.

Harrison was arrested by the FBI the next day. During his interview, he claimed that Rausini fatally shot Estes at the beach house and that he (Harrison) had no idea that Rausini planned on killing Estes.

Alonso was interviewed by LAPD detectives the following week. On October 15, he reported that while he had no specific knowledge of either of the homicides, other than rumors, he’d seen Rausini carrying firearms. In addition, Alonso stated Rausini had a relationship with a corrupt cop who’d tipped him off that Estes was an FBI informant.

Two days later, on October 17, Alonso changed his story, this time reporting that Rausini and Nason killed Ellenberger; that Nason committed the homicide; that Rausini disposed of the body; and that Rausini paid for the murder. Specifically, he stated he’d seen the “bloodstains” from the gun-shot wounds.

With respect to the Estes murder, Alonso claimed that he’d heard that Rausini had killed Estes and had done so because he was an informant. A month later, Alonso once again changed his story, this time stating that Harrison was responsible for killing Estes and that during the murder Rausini ran and hid in the garage.

THE EVIDENCE WAS SO overwhelming that the government began talking about seeking the death penalty. As a result, the court assigned Rausini new counsel that were qualified to handle a capital prosecution. George J. Cotsirilos, Jr. and Michael N. Burt took over the case in October 1997. They reviewed the evidence, met with Rausini several times, and listened to his version of the events.

In November 1997, AUSA Hall presented Rausini’s new attorneys with a plea bargain of life imprisonment. “You need to understand if you reject the offer,” said Cotsirilos, “the government intends to seek authorization from the Attorney General to ask for the death penalty.”

“I’m rejecting the offer,” he replied. “I’m being framed! I didn’t kill Lance. I didn’t kill Jon. Harrison and his friends are all lying.”

By 1998 the Justice Department was battling allegations of federal agent misconduct on three fronts. In Boston — in the Salemme case — the government was scrambling to cover-up the Whitey Bulger related misconduct which threatened to undermine the validity of well over a dozen mafia convictions. While in San Francisco, agent misconduct was threatening to undermine the Siriprechapong prosecution. In New York, the government was desperate to contain the fallout from the Scarpa related disclosures that resulted in several mafioso having their convictions vacated, and placing more than a dozen other convictions in jeopardy.

Weeks later, the San Francisco Chronicle ran a front-page exposé on Rausini’s case titled: Defense in Murder Case May Implicate State/Dealer Lured to His Death By Informant. The article focused on the allegations of law enforcement complicity in the Estes murder. Within the story the FBI’s informant, Farchione, was exposed for playing a role in the events that culminated in the murder.

Homicide Detective Porretta accused the FBI task force of concealing information that was material to his investigation. “When I found out how much this informant was involved, I was sitting here at my desk with my mouth open. The bureau went over the line.”

The article concluded with an observation that federal officials were “openly worry[ing]” that the agent’s role in Estes’ death may “undermine the entire case” against Rausini and his co-defendants.

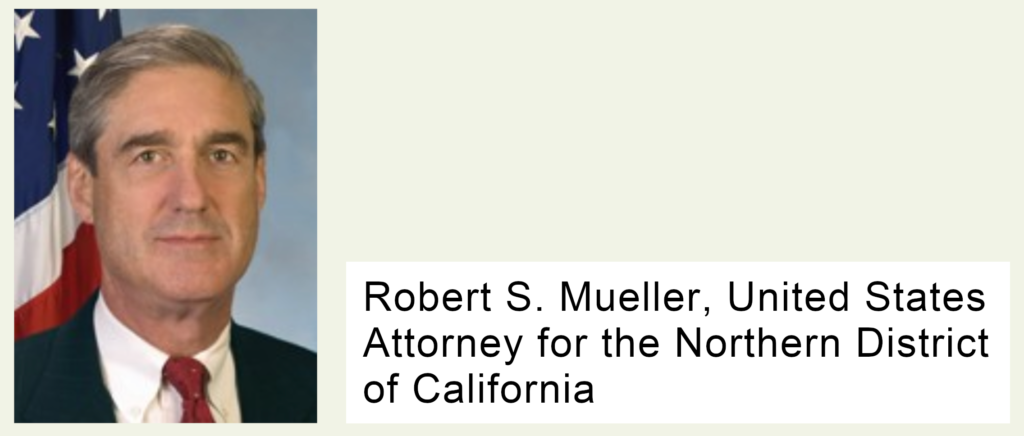

Following the Chronicle’s exposé, the U.S. Attorney for the Northern District of California, Michael Yamaguchi, was removed from the office and replaced later that year with Robert Mueller. As acting U.S. Attorney, Mueller announced the Rausini prosecution was back on track and that his office would be seeking the death penalty. Shortly thereafter, Mueller announced that he would personally prosecute Rausini’s case.

In April 1999, the government turned over thousands of pages of additional materials in discovery. Among the materials produced were LAPD homicide reports which indicated that three witnesses had reported that Nason had made statements boasting that he was a “hit man” and had been paid $30,000 for killing Ellenberger.

That summer, Rausini’s defense investigator, Paul Paladino, determined that the Sav-On-Drugs store in Newport Beach — the store Arranaga claimed to have purchased the Estes blood-flow towels from — never carried Cannon brand towels. Thus, confirming Arranaga had fabricated the “blockbuster” evidence the government claimed corroborated his account.

Around this same time period, the government turned over the telephone toll records of more than one hundred cell phone numbers used by Rausini and various associates. Those records showed dozens of calls to, and from, both Farchione, Barreiro, and Rausini on the day of the Ellenberger homicide and its immediate aftermath, i.e., during periods of time that the agent and his informant were denying they’d spoken with Rausini. Moreover, those records established that Farchione made no phone calls to Ellenburger on May 18th. Thus, confirming Farchione had fabricated his claims to the contrary.

In July 1999, the court set the trial date for spring 2000. The court ordered the government to provide all information concerning the nature and extent of Rausini’s interactions with Agents Barreiro and Blum as well as Informant Farchione.

Ten days later — on December 31,1999 — Barreiro took “stress” disability retirement, just as Agent Gervacio had done in Siriprechapong’s case. Specifically, by taking a stress disability retirement, agents cannot be compelled to provide testimony that will incriminate them. Thereafter, Blum also took an early “stress related” retirement.

Unbeknownst to Rausini’s attorneys, the collapse of Rausini’s prosecution was imminent. Just before a status hearing on January 5, 2000, Mueller approached Attorney Cotsirilos. Mueller told Rausini’s lawyers that he would be willing to explore a plea deal that “didn’t include Rausini’s death or a life sentence.” Mueller proposed a forty-year term.

Rausini was in the untenable position of having to risk a jury verdict based on fabricated testimony that could result in his being executed or plead guilty. Notwithstanding his innocence, to avert the risk of a wrongful conviction and a potential death sentence, Rausini agreed to negotiate a deal.

The following day, the San Francisco Chronicle ran an article announcing Nason had been arrested. Although, Nason refused to speak, Mueller told Cotsirilos that he had implicated Rausini in both murders, which was a lie.

Rausini was in a desperate situation. After a significant amount of badgering by Cotsirilos, Rausini agreed to plead guilty to avoid a possible death sentence. What other choice did he have? “It’s this or you get the needle,” said Cotsirilos.

RAUSINI STOOD in front of U.S. District Judge Susan Illston, on January 27, 2000. He hadn’t solicited Ellenberger or Estes murder, unfortunately, he couldn’t see an alternative to accepting the plea. At least an alternative that didn’t result in his death.

During the hearing, Rausini indicated that he wished to plead guilty to the solicitation counts. From the bench, Judge Illston asked, “What did you do with the money?” in reference to Estes’ bribe money.

“I delivered it to a government informant named Mark Farchione.”

The San Francisco Chronicle reported Rausini’s change of plea the next day. In the course of the article they revealed that Agent Barreiro had taken stress disability retirement amidst allegations of misconduct in Rausini’s case.

Cotsirilos arrived at the detention center later that day. Rausini immediately pointed out Barreiro’s retirement.

“Did you know about this?”

“No, Mueller withheld it,” replied Cotsirilos. “He lied. He sandbagged us.”

Rausini instructed his lawyer to call Mueller and “tell him I want to pull my plea. The deal is off.”

At Cotsirilos’ next visit, after speaking with Mueller, he reported that the U.S. Attorney had proposed an alternative to withdrawing the plea. According to Cotsirilos, Mueller had indicated an interest in speaking with Rausini regarding the Ellenberger and Estes homicides, including the allegations of criminal misconduct involving Barreiro, Blum, and Farchione. By cooperating with the government, Cotsirilos explained, Rausini could earn a significant reduction in his sentence. Cotsirilos claimed, however, that Mueller was insisting that Rausini be sentenced prior to their meeting.

On May 19, 2000, Rausini was sentenced to forty years. The headline in the San Francisco Chronicle read: Drug Kingpin Gets 40 Years.

“LEAVENWORTH FEDERAL PENITENTIARY was where they sent me,” says Rausini. One of the oldest federal prisons in the country, Leavenworth’s forty-foot high perimeter walls topped by barb-wire, as well as the ever present guards and gun towers, leaves no doubt that the prison was built to house the worst of the worst.

When U.S. Attorney Mueller and Special Agent Burroughs stepped into Leavenworth’s visitation room on October 11, 2000, the issue of Farchione, Barreiro, and Blum’s misconduct was threatening to destroy the government’s case against Nason and Harrison.

The first order of business on Mueller’s interview agenda were the allegations of corruption and misconduct. Although multiple individuals had made statements to the FBI and LAPD which supported an appearance of corruption, the U.S. Attorney’s tone indicated Mueller wasn’t convinced. Regardless, he said all the right things. “I’m only interested in the truth. If these agents engaged in criminal conduct, let the chips fall where they may.” Mueller asked, “Is Blum dirty?”

“I never spoke with Blum,” Rausini replied. “I only dealt with Mark Farchione and Shawn Barreiro — Shawn’s dirty. Now it’s my understanding — based on conversations with Farchione — that Barreiro was splitting the bribe money with Blum.”

The U.S. Attorney’s eyes met Agent Burroughs, and he said, “It’s my understanding you kept the money.”

“Me? No, I dropped off the money to Farchione — Barreiro’s bagman.” Mueller asked if Rausini knew of any additional money that may have gone to the agents. Rausini began discussing nearly two hundred thousand dollars in payoffs for protection and information; as well as the $1.5 million in product and the $300,000 in cash that Farchione and Barreiro had stolen from Ellenberger and Robles. “That was a couple of years before the Estes thing.”

Mueller cut Rausini off. He wanted to focus on the allegations of improper conduct in connection with the “Operation Avalanche” investigation underlying Rausini’s prosecution. Burroughs pulled out a legal pad and pen, and Mueller asked Rausini about Estes’ bribe payments. Rausini explained that he and Nason had met with Farchione at the Mondrian Hotel in West LA, as Burroughs scribbled away on his legal pad. Rausini discussed the circumstances surrounding the delivery of the initial $50,000 payment; the second $45,000 payment; and the third $5,000 payment.

“What was the hundred thousand for?”

“That’s what Barreiro was charging to tank the case.” That seemed to agitate Mueller and he redirected the line of questions away from Barreiro and Blum to the Estes homicide. “You asked Harrison to kill Estes, why?”

“First off, I never asked anyone to kill Lance (Estes). Barreiro said there was an informant in Estes’ organization.” According to Barreiro the informant had provided the information that led to Meacham being arrested and two hundred thousand dollars’ worth of ice being seized. “But I never suspected Estes of being the snitch.”

“Then why was he killed?”

“Because Farchione said he was a threat. After Estes had tried to back out of the arrangement, he became a liability. Barreiro and Farchione were exposed.” Rausini described the meeting where Farchione told Harrison that Estes was an informant, and to kill him. “But he didn’t want it done in San Francisco — Estes lived with his girlfriend.” Rausini explained that Farchione instructed Harrison to kill Estes in Los Angeles, and to “make sure that no one [found] the body.”

Rausini disclosed that Barreiro had leaked to Farchione that Estes had agreed to cooperate with the FBI. Unbeknownst to Rausini at the time, but known to Mueller, Estes had also offered to cooperate against corrupt law enforcement in exchange for consideration in his case.

This made him a liability. Barreiro and Farchione, as co-conspirators would have been vulnerable to conviction.

“Barreiro is knee-deep in this thing. Farchione ordered the hit after he (Barreiro) leaked the information about Estes being an FBI informant.”

“Wait a minute, you don’t know that,” Mueller countered. “Even if what you’re saying is true, it’s not conclusive proof that Agent Barreiro was involved. You don’t have direct knowledge.”

“Of course, he was involved; he leaked the information.” Also, while Barreiro was a Northern California agent, he wasn’t on the San Francisco task force, he was based in Silicon Valley. Blum, on the other hand, was. Therefore, Blum had to have given the information to Barreiro. “Barreiro might as well have pulled the trigger.”

“Agent Barreiro did not pull the trigger!” snapped Mueller.

“What did he think was going to happen when he identified Estes as a snitch?” asked Rausini. “Did he think these guys were going to thank Estes for helping take a bite out of crime?”

The blood drained from Mueller’s face. Based on Rausini’s information, Mueller was now the lead prosecutor in a case involving an agent that had leaked confidential law enforcement information, setting in motion a chain of events that led to the murder of an FBI informant.

Mueller then asked about the weapon used to kill Ellenberger. “Ellenberger wasn’t shot!” gasped Rausini out of exasperation at Mueller’s ignorance, “Nason choked him out.”

“Then why’d you plead guilty?”

“I was looking at catching the death penalty on false charges based on fabricated evidence that your witnesses colluded to manufacture.”

Mueller asked who had paid Nason the $30,000 he’d claimed to have been paid for killing Ellenberger. But Rausini didn’t know. Nor did he know the individuals who Nason had made those statements to.

The more Rausini spoke, the more it became apparent that the government’s case was based on lies. Rausini could almost feel the knot in the pit of Mueller’s stomach.

Rausini explained that after he’d found Ellenberger dead, Rausini called Farchione —whom, federal law enforcement, had led him to believe was an FBI agent — who instructed him to get rid of the body. “Didn’t you check the phone records?”

“What records?” asked Mueller. Rausini explained that the cell phone billing records proved he’d spoken with Farchione and Barreiro multiple times on the day of the murder, as well as a couple dozen times within the next two weeks. Mueller looked ill at the revelation.

When Mueller asked about the “blood-stains” Alonso had seen, Rausini almost laughed. “There were no blood-stains, because there were no gunshot wounds. Nason choked Ellenberger out.” Rausini challenged Mueller to explain how Alonso’s story had matched Harrison’s and Farchione’s when all three men had reported the same false, fabricated, and physically impossible facts. “What did the forensic examiners say? I know they couldn’t have found any evidence of blood.”

Mueller reluctantly admitted, the FBI and LAPD’s top forensic examiners hadn’t found any forensic evidence. Both of his high-profile cases were falling apart.

Rausini told Mueller that Harrison and Nason’s lawyers knew that Farchione and Barreiro were dirty. “They know your witnesses’ statements are concocted. Read Harrison’s girlfriend’s grand jury transcript; your witnesses were all attending meetings. Melendez overheard them discussing different scenarios in which I shot both men. Harrison and Nason’s lawyers had to know that your witnesses concocted their stories because when they made it all up their clients were at the meetings . . . Barreiro’s dirty and the FBI’s Operation Avalanche task force was leaking like a sieve,” said Rausini. “You’re heading for a fucking shipwreck.”

Mueller was three months away from a high-profile trial in which he now knew multiple witnesses — including two agents and an informant — were lying. The government’s theory of prosecution was profoundly flawed.

“We’re going to investigate the information you’ve provided and, if we can corroborate it, we’ll be back.”