THE YOUTUBE VIDEO was made-up of grainy, black and white, washed out images. Mostly, it was a jumble of documentary-style shots cut with a camera phone; home movie-ish cinematography of a solitary figure scribbling in a journal while singing. The video jumps between scenes of a prison rec yard with barbwire fences and a cinderblock walled jail cell, complete with a stainless steel toilet/sink, and a barred door and window.The singer appeared to be Karey Lee Woolsey, clad in a prison garb wifebeater-tanktop and a grungy jumpsuit, although, the camera never gets a clear view of him. His facial features are obscured by shadows and clever camera angles. It is, however, undoubtedly Karey crooning, These Walls Around Me, a Kidd Rock-style ballad about struggling with incarceration.

In all respects, it appeared to be an authentic makeshift music video, produced using a contraband phone camera most likely smuggled into a prison and adeptly placed into the hands of a professional.

The video was released July 5, 2013—five years into Karey’s twelve and a half year prison term—along with his album, A Million Miles Away. Within the first week, the video experienced lukewarm success. The album, however, skyrocketed to number four on the Billboard Heatseekers chart and hit number three on Amazon’s Alternative chart. An extraordinary achievement for an artist, and an unprecedented phenomenon for a federal inmate.

WHEN KAREY ARRIVED at the Coleman Federal Correctional Complex’s low security prison in Coleman, Florida in late 2016, he sought me out. Between the medium secure prison in Estelle’s Federal Correctional Complex in South Carolina and Yazoo Federal Correctional Complex’s low security facility in the middle of Mississippi, Karey had spent over eight years inside. He was within a year of being released to a Fort Myer’s halfway house. Karey had read an article in Rolling Stone based on a manuscript I’d written and mistakenly believed I could get him into the magazine.

He gave me his news clippings and the Readers Digest-version of his story. It sure sounded like a story tailor-made for Rolling Stone. Unfortunately, I had to explain that the reporter I’d worked with, Guy Lawson, told me he’d personally spoken with his editor at the magazine and he’d refused to consider giving me a byline. According to Lawson, Rolling Stone would never entertain a submission by Matthew B. Cox, a federal inmate.

“Lawson’s absolutely unwilling to help me get into another magazine either,” I informed Karey. The reporter’s only interest in me, at this point, is taking my subjects and research, and using them to further his own career. “He’s not gonna help me as a writer.”

“Shit, bro, that sucks. I had my heart set on Rolling Stone.” The most I could offer Karey was a spot on a website I was trying to put together (at the time). This seemed to satisfy him. “Here’s the thing, I don’t wanna come off like a kingpin,” he said. Like many inmates, Karey was embarrassed about being in prison. He believed the stigma would damage his future music career. Karey is (if nothing else) fiercely concerned with his image.

As a result, he wanted me to minimize the events that led to his incarceration and focus on the events that led to his top ten album. He didn’t ask me to lie, just limit the scope of the story of his marijuana operation. He certainly didn’t want me to mention the cartel.

“Yeah, uh, I’m not gonna do that Karey,” I said. I’m not suggesting I’m bound by journalistic ethics or some code of conduct, but I write true crime. I don’t know anything about music, however, I do know crime. Besides, I told him, I seriously doubt anyone in the music industry would look down on a guy who got busted for selling marijuana. I don’t write watered down, crybaby, poor me stories.

I made it very clear that the only thing I was willing to do was dig-in; order the DEA reports, indictments, transcripts, etc. I’d talk to his family members and codefendants, put together the true crime and a barbwire backstory, but that was it.

“You’ve gotta make a decision,” I said. “You can either spend the rest of your life hiding from this, or you can own it. If someone has a problem with it, fuck ’em. Tell ’em to kiss your ass.” I told Karey, “That’s what a rock star does. He’s the guy who deserved to have his voice heard. He’s the guy who deserves to be famous.”

ROUGHLY A MONTH after Karey was sentenced on August 4, 2008, he was transported to Estelle Federal Correctional Institution. An overcrowded medium security prison. The bulk of the 1,300 inmates that populate Estelle were Mexican and black gang members. Stabbings and riots were common.

Karey kept his head down and stuck to himself. In late 2009, he was transferred to the disciplinary low security prison at the Yazoo Correctional Complex in Mississippi. Despite the prison’s “low” security designation, Yazoo or “The Zoo” was a rough place. Eighteen hundred inmates trying to carve out a spot in a prison designed for a thousand.

THE BRUNETTE walked into the visitation room sometime in early 2013. She was an old friend from middle school. Sharron [1] had tracked Karey down on Facebook, not long after he’d been sentenced. They’d been corresponding via email and she wanted him to release an album. Karey had recorded over a dozen songs just prior to his incarceration and they had been dormant until now.

[1] Name has been changed.

Sitting across from one another in the crowded visitation room, knee to knee, Sharron told him “It’s going to be great. Everyone loves your music.” She told him she’d take care of everything. “Karey you’ve gotta trust me.”

He’d been writing songs and playing the originals with a band he’d put together in The Zoo’s recreation center for years. Honing his skills as a musician and going nowhere. The compositions were stacking up, but the time was suffocating him. “Yeah, okay,” he grunted. “Pull the trigger.”

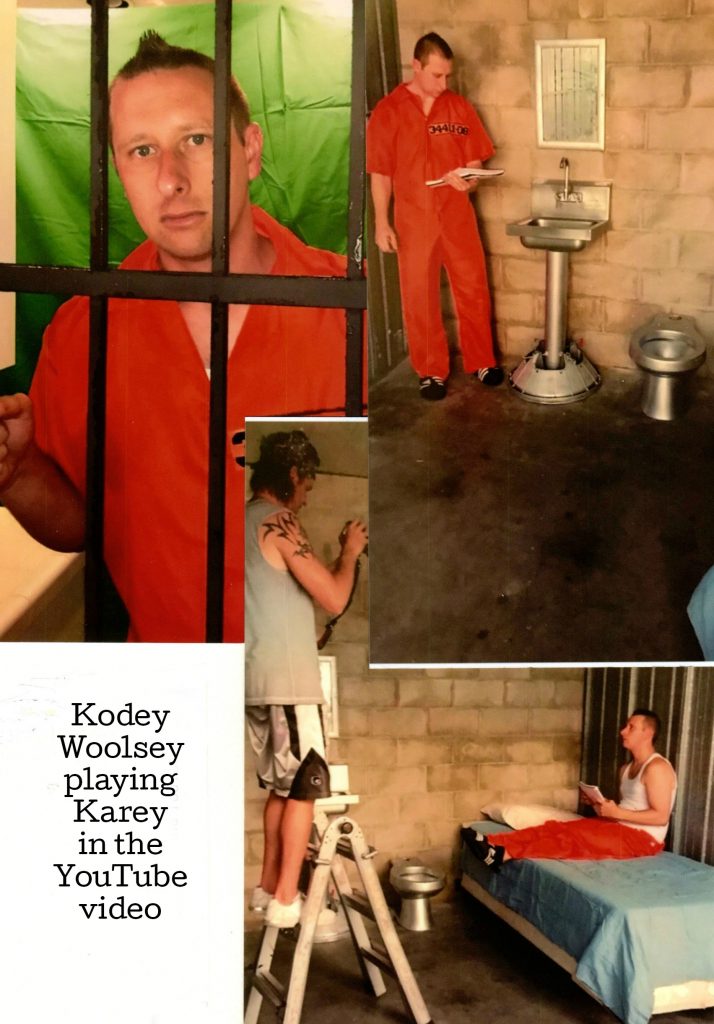

Karey didn’t expect anything to come of a self-published release by a federal inmate. However, Sharron got together with Karey’s older brother Kodey—who bears a resemblance to Karey—and a mutual friend, Michael Harvey.

“Mike (at the time) was an amateur videographer,” says Kodey. “He had some experience shooting videos for local bands. He shot the whole thing and edited it too.”

They filmed most of the video in a warehouse Mike rented—a couple scenes were shot at a convenience store payphone and Mike’s residence. They furnished the warehouse with a mirror, a bed and sink. Most of the scenes were set against the backdrop of scored concrete block walls and prison bars.

Kodey’s wife sewed Karey’s federal inmate registration number onto a jumpsuit they purchased online. Armed with a Sony HD camera Mike filmed Kodey singing Karey’s These Walls Around Me.

“I wanted to do it for Karey,” recalls Kodey. He was hoping the video would promote the album and awareness of the draconian harsh punishments that federal courts impose on those convicted of the crime involving trafficking marijuana. “Karey and Danny spending over a decade in prison for marijuana, it’s absurd. I don’t care how much they were convicted of.”

Karey contacted USA Today, and they wrote a very flattering piece on the federal inmate’s pending album. A Million Miles Away was released on July 9, 2013 and hit number four within a week. The amount of sales on iTunes, CDbaby and Amazon were unexpected, Karey tells me. The album was available to all federal inmates throughout the Bureau of Prison’s music service. “Guys on the compound (the area within the prison’s razor-wire fences) were walking around singing Busted and Chains,” he says. “It was pretty cool.”

Articles started appearing in newspapers. Two months later Forbes.com ran the article, Singing A Tune From Federal Prison and High Times printed Jailhouse Rock. Then Pit Bull’s management contacted Sharron and several other big-time music producers in the industry begin making inquiries. Just as the sudden kick start to Karey’s music career began to gain traction, the wheels came off.

Unfortunately, at first glance, the YouTube video appears that Karey had somehow shot a music video within the prison. Neither Warden Mosely—the angry African-American woman who ran The Zoo—or the lieutenant over the Special Investigative Services (SIS)—the department responsible for conducting investigations within the prison—were happy about that.

Karey stepped into the visitation-prep-area—the room where inmates are strip-searched entering and exiting the visitation room. His family had traveled from Fort Myers and they were just on the other side of the door. That’s when the correctional officers (CO) slapped a pair of handcuffs on his wrists. As his mother was told she wouldn’t be seeing her son for a long long time, Karey was escorted to the Special Housing Unit (SHU) i.e. the disciplinary unit. The officers wouldn’t tell Karey why he’d been placed in “The Hole.” However, the word was that the warden and the SIS lieutenant had learned of Karey’s video.

Initially, Karey was placed in a two man cell with no roommate—although during his time in the SHU other inmates came and went. None were placed in his cell for more than a few days. For the most part Karey was housed in a solitary cinderblock room with nothing but a bed, a stainless-steel combination-toilet-sink and a shower. He was only permitted to go to rec once a week for an hour. There, the inmates were surrounded by tall walls and a makeshift roof. They were kept separated by chain-link fences.

“It’s like a human dog kennel,” says Karey. “There’s no sunlight or interaction. There’s nothing to do but walk around in circles.” On his way back from one of his rec hours Karey asked an officer why he was in the SHU, and when he’d be getting out. It had to be a mistake. “The guy started to laugh and said, ‘You got a warden hold on you, Woolsey. You ain’t goin’ nowhere, no time soon, so get comfortable.’ I couldn’t believe it.”

After a month Karey was allowed to make one phone call. He called Sharron and told her to ask his Facebook friends to send him “stuff to read.” Within days the SHU was flooded with nearly seventy books and well over a hundred magazines. “Bro, when all that mail arrived, I remember feeling so loved, you know?”

Karey spent Thanksgiving, Christmas and New Years in solitary confinement writing letters and songs.

Sometime in mid January 2014—two months after Karey had been tossed into the SHU—Warden Mosely walked through the unit. Karey banged on the steel-door of his cell and yelled, “Warden! Warden Mosely! Can I please talk to you? Please!”

She stepped up to the upright rectangular plexiglas window in the door and said, “My god! Inmate Woolsey, you still in here?” She told Karey she had gone on vacation and forgotten all about the hold she’d placed on him. Mosely agreed to have him released the following day, however he was to stop by her office the moment his feet hit the compound.

When Karey walked into the warden’s office the next morning, she peered at him from behind her desk. “As an inmate, there’s a line you simply don’t cross,” she informed him, “and you’ve been skipping back and forth over that line since you got here.” She knew all about Karey’s album and his radio and newspaper interviews. She’d been following him on Facebook. The warden glared at him and growled, “This is where it ends, understand?”

“Yes, ma’am.”

Karey hadn’t actually done anything wrong, yet he’d spent over two months confined to a small, filthy cell with no sunlight. Two months being fed through a slot in the door. Two months lying awake, listening to his fellow inmates screaming to one another up and down the hallway. All that time for nothing.

A few months later, Karey convinced one of the officers in the recreation department to “accidentally” leave out the VCR. Karey was able to rig the device to record himself playing and singing an acoustical version of Reach For The Star, a song he’d written while in The Hole.

He then carved a square into the pages of a hardback book, placed the tape inside and mailed it to a producer buddy of his. Mike Dunn re-mastered the recording, and put it on iTunes, CDbaby and Amazon.

“We released Reach For The Stars on April twentieth (420),” chuckles Karey, “as kind of a fuck you to the Bureau of Prisons. Now that was a song made within the walls, right underneath their noses.”

SOMETIME IN APRIL 2015, Karey read an article in Rolling Stone titled The Dukes of Oxy, by Guy Lawson. Seven thousand words based on a true crime memoir written by Matthew Cox in conjunction with Douglas Dodd. The article chronicled Dodd and his friend’s adventures as drug smugglers. At the time Dodd had been released. I, however, was still incarcerated at Coleman.

“I remember thinking, how cool it would be to be in Rolling Stone,” says Karey. “Every musician wants to see their name in Rolling Stone.”

Karey spent the remainder of his time at The Zoo in the Residential Drug Abuse Program (RDAP).

“A lot of guys get kicked out,” says Karey, However, the psychologists that ran the program never gave Karey a hard time. “My band and I played all of the RDAP and GED graduations—nineteen of ’em. Plus, we played all the staff parties, so I sailed through the program.”

Upon completion of RDAP, Karey’s sentence was reduced by one year, but he was nowhere close to being released. He had, however, requested a sentence reduction from President Obama’s Clemency Program.

They gave Karey an attorney and put together a strong case. He said all the right things during his interview. His friends and family mailed in many letters in support. There were articles in several newspapers regarding Karey’s hopes for a sentence commutation. His chances seemed good.

At the time, twenty states had some form of legalized marijuana, Colorado and Washington allowed recreational use. It seemed insane to keep him in prison for something that was practically legal.

According to Karey, his petition made it all the way to President Obama’s desk.

“He personally denied it,” says Karey. “The Pardon Department never gave me a specific reason.” However, one of the restrictive criteria set forth for commutation limited inmates affiliated with large scale drug organizations from consideration. There’s little doubt Karey’s connection to the Sinaloa Cartel played a large part in Obama’s decision.

In late 2016, Karey was bussed from Mississippi to Central Florida. That’s where we met—at the Coleman Federal Correctional Complex. That’s where I told him he wouldn’t be getting into Rolling Stone. Not if I was involved. Not according to Guy Lawson.

“All I can do for you is write out your story,” I told him. “The way people on the street see it, I’m just some guy in prison scribbling in a note pad. People don’t believe anything good can come out of a prison.”

“That’s too bad,” replied Karey with a sigh. “I really feel like my story’s Rolling Stone material.”

At the time of our final interview Karey was scheduled to be released in November 2017. Stronger than ever, and ready to break back into the music scene and, with some luck, the industry. “This time,” Karey said, “I’m not giving up. I’m not taking no for an answer. I’m not accepting anything but success; and if anyone doesn’t like it, ” he shot me a mischievous grin, “they can kiss my ass.”