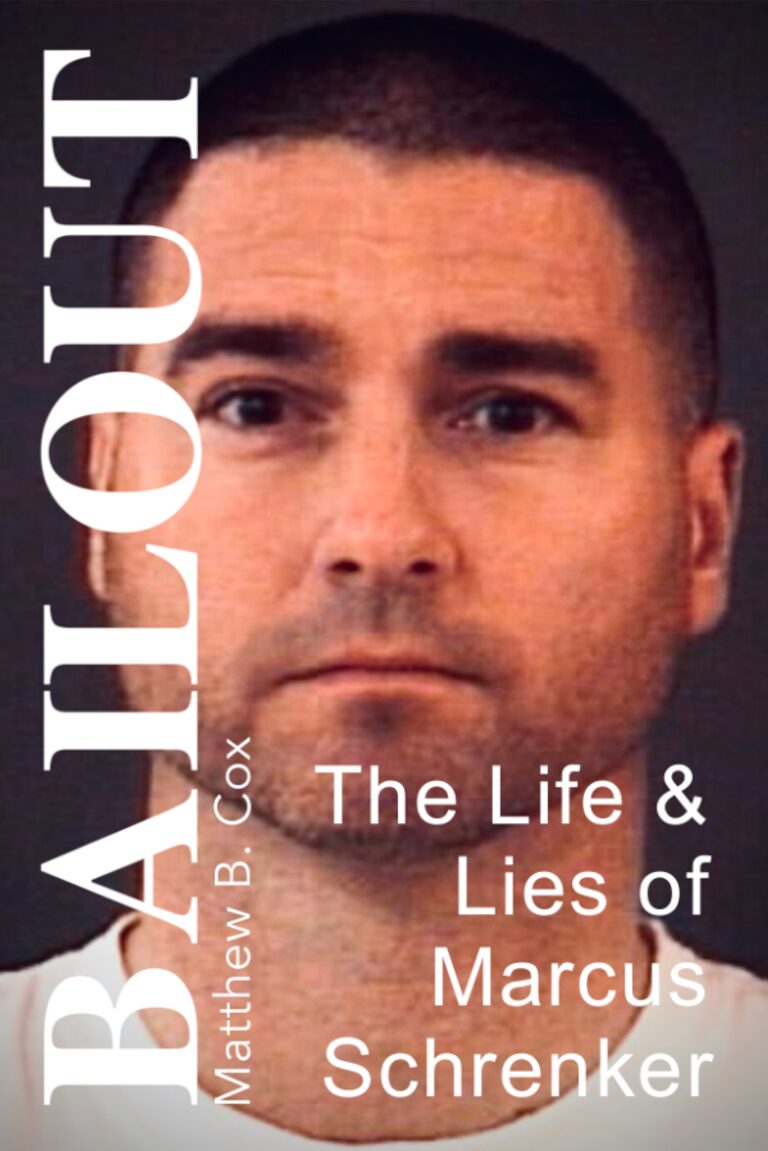

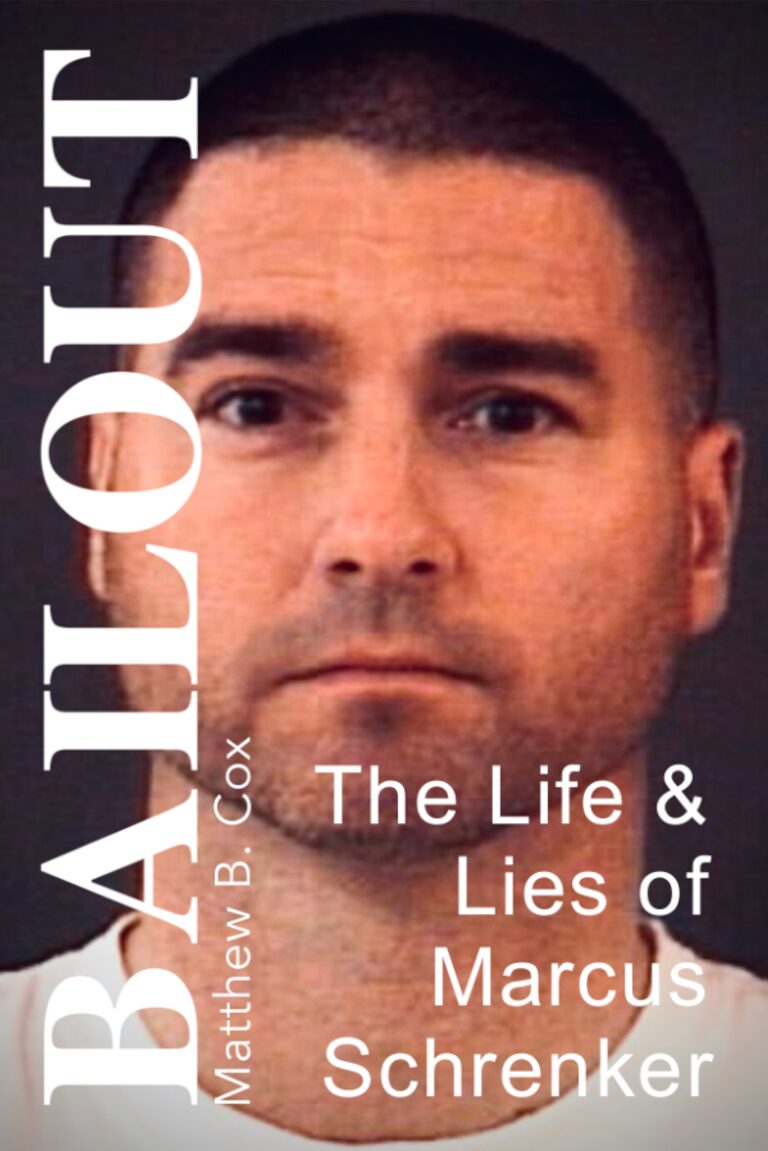

BAILOUT: The Life & Lies of Marcus Schrenker

By Matthew B. Cox

AT NEARLY 24,000 FEET over Alabama, Schrenker shouted “Four-two-eight-delta-charlie!” into his headset. He was cutting through the freezing January air at 300 mph in a single engine turbo-prop Piper Meridian. “Atlanta Center! This is an emergency! I’m experiencing severe turbulence and my windshield is spider cracking … Windshield has failed!” At just shy of five miles above the Earth it was a devastating admission.

Over 200 Miles away in Peachtree City, Georgia, half a dozen Air Traffic Controllers immediately scrambled around the FAA air route traffic control center, desperately rerouting commercial air traffic

“Four-two-eight-delta-charlie,” squawked the radio, “descend immediately! Descend immediately!” The autopilot had been programmed for a rapid descent to 10,000 feet, where the aircraft would level off and fly out over the Gulf of Mexico. Schrenker flipped it on, the Piper nosed over violently and the emergency descent began.

“Atlanta Center, windshield has failed! I’m bleeding profusely,” he shouted. But like everything in Schrenker’s life at the time, it was a lie. He was going through a vicious divorce with a woman who despised him. The U.S. economy was imploding, along with Schrenker’s business and he was facing a 20 year prison sentence for securities fraud. But he had a plan to escape it all. He wrapped his headset around the yoke and crawled from the cockpit into the seating area. He slipped on the parachute as the aircraft plummeted, and doubled-tied a drop bag filled with roughly 50 pounds of gold to his ankle.

Schrenker could still hear the FAA air traffic controller screaming, “Descend immediately!” from the cockpit, when he slipped a couple oxycodones into his mouth, chewed them up and swallowed the bitter fragments. He grabbed the aluminum door handle with both hands. For a split second he thought about his soon-to-be “widowed” wife and the three beautiful children he was abandoning. Schrenker told himself the kids were better off without him and twisted the handle with everything he had.

According to his plan, once the aircraft reached 10,000 feet it would level off, fly out over the ocean, run out of fuel and silently plunge into the Gulf of Mexico; disappearing underneath 1,000 feet of water. But that’s not what happened.

About halfway into turning the door handle, the hull pins retracted, the atmospheric seal broke and the decompression simultaneously blasted the door, along with Schrenker, out of the cabin. He slammed into the door and the clamshell-stairs snagged one of the parachute’s nylon vest straps. The cabin-door yanked Schrenker through the negative 40 degree Fahrenheit air, slung him around by the nylon strap and smashed him into the side of the aircraft.

Between the 300 mph wind and the pitching and yawning of the plane, Schrenker was being repeatedly bashed into the aluminum fuselage of the Piper. Just when he thought, This can’t get any worse, the parachute deployed and was instantly shredded by the hurricane strength relative wind.

Suddenly, the plane pitched upward and his vest’s nylon strap snapped, sending Schrenker tumbling through the air with the useless tattered remnants of the parachute trailing above him.

The Meridian disappeared into the distance as the gold dragged him toward the ground and his inevitable death. This wasn’t a part of my plan, thought Schrenker. On the upside, the oxycodone was kicking in.

MY NAME IS MATTHEW COX and I’m a con man. I’m currently serving a 19.5 year sentence at the Federal Correctional Complex in Coleman, Florida for a slew of bank fraud related charges; and I’m 100 percent guilty of them all. As prisons go, Coleman’s not a bad one. The complex is clean and the inmates are mostly nonviolent. Mostly.

There’s a recreation yard, leisure center, vocational training…everything you need to keep 1,800 prisoners occupied. I spend most of my time in the library, writing my fellow inmates’ stories. Sometimes it’s a memoir. Sometimes it’s a true crime.

That’s where I was in late 2013—putting the finishing touches on an inmate’s memoir—when Marcus Schrenker slipped into the seat across from me.

“I understand you write guys’ stories,” he said as I looked up at him. Schrenker was tall and lean with the traditional handsome features of a WASP. “I’ve got one for you…” He told me the press had gotten it all wrong. The media coverage of my own story had been tweaked and twisted to make me into a monster, so, I was susceptible to the idea of the evil media machine. “The truth is,” Schrenker continued, “I shouldn’t even be in prison.”

“So let’s hear it,” I said.

Over the next hour Schrenker told me he’d been the victim of a group of disgruntled clients that had lost money in some bad investments. “I’d sold a bunch of index annuities that ended up underperforming,” he admitted. Schrenker’s eyes turned soft and his blank expression morphed into a sad puppy dog. “That wasn’t my fault. I can’t be blamed for the market, Matt.”

He seemed sincere, although, emotionally detached.

While Schrenker was struggling to convince the insurance companies to return the clients’ funds, his gorgeous wife discovered he was having an affair. She then pilfered an offshore FOREX currency account—bilking clients out of over $1.5 million—for which he was ultimately charged.

“Why take the fall for your wife?”

“I was supposed to be dead,” he snorted, “remember?”

It all sounded very contrived. Very convenient. But I wanted to believe him. I wanted the story of Marcus Schrenker that everyone had missed. So I agreed to meet Schrenker that weekend to start working on a detailed outline of his story that I would then turn into a true crime.

That night, I called my literary agent at the time, Ross Reback, from the pay phone in my housing unit, a massive barrack-like building. I wanted to bounce the idea of writing a non-media manipulated, honest true crime about Schrenker off Ross. No sound bites or bullshit. “His version is vastly different than anything I’ve seen on CNN,” I excitedly said into the receiver. “He had a ton of press and—”

“Matt, he’s lying to you,” Ross interrupted. “I remember the case and the guy’s a shyster.”

“No, he got railroaded by the press and . . . he’s not a bad guy.”

I could feel Ross grinning on the other end of the phone. “Here’s what I’m willing to do,” he said, “I’ll pull some articles offline and mail ’em to you.”

That Friday, I received roughly twenty articles in the mail and a note from Ross stating there were more coming.

By the time Schrenker and I met again, I had a much more defined account of the official story; and I knew something wasn’t right with Schrenker. Most of the articles contained accounts of his deceptions. His lies. But I didn’t want to pre-judge him. I wanted to hear his version.

Eventually, I obtained copies of several lawsuits, federal and state indictments, transcripts, victim statements and related documents. That’s when I realized Schrenker was nothing short of a pathological liar; and every story he was telling me was riddled with half-truths and/or blatant lies. Here’s the thing, I’ve read some material on the condition. Despite what most people think, true pathological liars are rare. I was fascinated by his mental state and I couldn’t let the opportunity pass. So, I decided to coax, cajole, and yes, con the truth out of him.

What follows is the story Marcus Schrenker didn’t want you to know.

“THE FIRST EVIDENCE of pathological lying shows up during preteen years, in children who have a faulty superego,” says Dr. Bryan King, Psychiatrist at U.C.L.A. School of Medicine. The environment in which a child is raised may be so overwhelmingly traumatic, lying serves to support repression. Patients with pseudologia fantastica pathological disorder often report traumatic childhoods. “[These psychologically damaged children,] think they can say anything and get away with it.”

MARCUS SCHRENKER was born in November 1970, near Chicago, in Merrillville, Indiana, just across the Illinois border. According to Schrenker, he was raised by an abusive stepfather and an alcoholic mother. When the screaming started Schrenker would lay in the front yard and listen to them yell at one another while watching the commercial jets fly over the house. Someday, he’d think, I’ll be on one of those planes. Someday I’ll escape.

Their behavior was so erratic, as a boy Schrenker couldn’t invite anyone to the house. “Uh uh. No way,” he’d tell his mother if she suggested having a party or sleepover with his friends. “Not in our house!” It’s not like he could have a pizza party with his mother and stepfather chucking ashtrays at each other.

DURING OUR NEXT MEETING I informed Schrenker, at some point we had to address the habitual lying issue. The media coverage of Schrenker was saturated with stories of his deceptions. There was no avoiding it. Initially, he denied having a problem. “It’s bullshit,” he said. “I’m not some kind of liar.”

It’s important the reader trusts you, I told him; admitting to something embarrassing, like masturbating or occasionally lying, will help build that trust. “Everyone lies,” I assured him. “I’ve certainly told my share.”

Schrenker’s eyes drifted around the library for a full minute and I could picture the gears turning in his mind, trying to decide if he should admit to lying for the sake of fooling readers into trusting him. In the past he’d always denied the lies.

Reluctantly he told me the first lie he could recall. It was summer break and Schrenker was 13-years-old; a couple neighborhood kids stopped by his parents’ house. They wanted to hang-out, “Maybe play some Space Invaders or Asteroids.”

His mother and stepfather had been bickering most of the morning and it was only a matter of time before the bickering erupted into a screaming match or possible violence. “Sure,” Schrenker told the neighbors, “but we can’t play here…my stepdad’s painting the living room.” That was the first lie.

The lying quickly expanded to cover for missing homework assignments and skipping school. Carefully, weighed out, lies with beneficial consequences. Unfortunately, over time his coping mechanism mutated into a cerebral dysfunction, whereby Schrenker began lying simply to feel good about himself. Eventually, he confided, at times, Schrenker simply couldn’t control it and he’d lie for absolutely no reason.

Schrenker would spend a Friday telling classmates that his stepfather was taking the entire family to Florida for a week long vacation; only to tell his fellow students three days later that the trip had to be cancelled because his little brother broke his arm.

The few times Schrenker’s parents and teachers caught him in the act, the lies were chalked up to harmless fibs and not the abnormality they’d become. Eventually, these non-beneficial lies became self-destructive.

“IT HAS TO DO WITH self-esteem,” says Robert Reich, M.D., a Psychiatrist of Psychopathy. “Pathological liars want to be someone else because they aren’t happy with themselves.”

BY THE TENTH GRADE, Schrenker was dating Beth Coldwell*, a vivacious, trusting senior. Two months into their relationship Schrenker slept with a random girl from the neighborhood. “I didn’t use a condom—I should’ve, but I didn’t,” said Schrenker. “The next morning it burned a little when I peed. Still, that night I slept with Beth.”

* Footnote: Name has been changed.

Within days Schrenker began having a creamy discharge. By the time he saw the doctor Schrenker’s urethra felt like it was on fire every time he relieved himself. He knew what STD’s were, but he’d never heard of gonorrhea, specifically. Schrenker told the doctor about the girl he’d slept with.

“Have you had unprotected sex with anyone else?” asked the physician.

“My girlfriend.”

The doctor wrote Schrenker two prescriptions for penicillin—one for him and one for his girlfriend.

That night, Schrenker met Beth at a pizzeria to discuss the burning. She already had her suspicions. “What’d he say?” she asked. Schrenker explained he’d contracted gonorrhea, however, he wasn’t mad at her.

“Me?!” snapped Beth, “I haven’t slept with anyone.”

Schrenker sighed, then chuckled softly to himself, “This doesn’t have anything to do with cheating.” He then explained that gonorrhea had been around since the beginning of humanity and would continue to be around until its extinction. The disease is primarily caused by the build up of bacteria and spread through sexual intercourse; which is absolutely untrue. “Basically, it comes from women that don’t keep themselves clean.”

Beth threw her hands over her mouth in shock. “Marc, I take a shower every day, sometimes two…” She glared at him and hissed, “Are you sure he said it was me?”

Schrenker placed her prescription on the table and said, “He wants you to take ’em twice a day for the next ten days and start taking baths.”

Beth burst into tears and pled with Schrenker not to break up with her.

Less than two months later, Schrenker met a drunk, flirtatious little hotty at a party. Before long he’d taken her in a spare room and they stripped one another’s clothes off. Neither thought about using a condom. Unfortunately, by the time his urethra was inflamed and burning he’d already had sex with Beth.

Days later, after picking up a couple prescriptions from the doctor, Schrenker stopped by Beth’s house. When he handed her the script she gasped, “Ohmigod, I’m taking two or three baths a day. I’m keeping myself clean.”

“The doctor said this might be a recurring problem for you.” Schrenker told her she may have to deal with gonorrhea outbreaks for the rest of her life. If she continued dating Schrenker she certainly would.

As far as Schrenker knew, Beth never actually found out he’d given her a venereal disease, twice; however, a month later she did find out he’d slept with her best friend and the relationship ended.

“Over the years,” Schrenker recalled, “virtually every girl I’ve dated eventually noticed the lying.” He didn’t lie to them out of malice; it was typically done to cover up some inadequacy or to impress them. Initially, they were always quite impressed, but after a few months they’d learn to see through the lies. “No woman wants to date a habitual liar.”

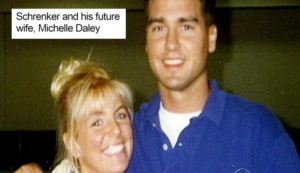

During Schrenker’s junior year at Purdue University—in mid 1993—he met Michelle Daley. She was a size zero and an absolute knockout. He impressed her with stories of flying T-38 twin-engine supersonic jets in the course of his internship with NASA; and a dozen other things he hadn’t done. She wasn’t aware of Schrenker’s self-defeating nature. “Michelle thought I was someone special,” he told me. “She was different than the other girls I’d dated. Michelle would say things like, ‘Someday we’ll have a family’ and ‘You’ll make a great father.’ None of the other girls said stuff like that.”

Eventually, Michelle noticed his “little white lies,” but she never made an issue of it. She was everything he’d ever wanted in a woman; a gorgeous, family-oriented enabler.

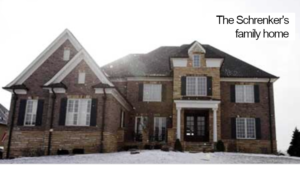

WITHIN A FEW YEARS Schrenker had earned a double major in Aviation Technology and Finance, and a Master’s Degree* in Finance. He and Michelle were married and had a baby.

* Footnote: Despite Schrenker’s assertion, I have never been able to confirm Schrenker holds a Master’s Degree.

Schrenker took a job in Indianapolis with John Hancock as a financial planner—a glorified insurance salesman. He spent his days in a cubicle surrounded by a sea of dozens of other “planners” talking into headsets; trapped in maze of grey polyester and aluminum workstations, calling shitty leads provided by Hancock’s marketing department. It took roughly 100 calls to generate one sale.

His credit cards were maxed out and he felt like he was dying inside—the slow death of middleclass debt. That’s when Schrenker started thinking about niche marketing. Companies like AARP and USAA make huge profits by catering to one specific group. He was a pilot after all.

“My first call,” Schrenker told me, “was to the senior pilot for American Trans Air. I introduced myself, stuttered slightly, and explained that I’d just graduated from Purdue with my degree in finance and aviation. He said, ‘So you’re a pilot?’ and I told him I was… He bought a million dollar life insurance policy right over the phone.” The next pilot Schrenker called purchased insurance and signed over his mutual funds to John Hancock. Then there was a captain with Delta… Schrenker’s closing ratio went up to one in two.

By the time Schrenker incorporated Heritage Wealth Management, leased an office and filled it with financial planners, he’d perfected his sales pitch. It was late 1997—the beginning of the dot-com boom—and Internet-based companies and related fields’ stock prices were increasing exponentially. Investors were making massive gains in companies like Cisco, Microsoft, Intel, Amazon, etc. Schrenker focused on senior captains making in excess of $200,000 annually, while maintaining large portfolios with firms like Charles Schwab, Chase and Dean Witter. The young flashy financial advisor would give them a firm handshake and says, “Captain, I understand you flew A-4’s in Vietnam?” or “You graduated from the Air Force Academy?”

They’d stammer, “Well, yes, I did Marcus.”

Schrenker would casually let them know he’d been a F-15 fighter pilot during Desert Storm while in the Air Force (he would have been 20-years-old at the time, making Schrenker the youngest fighter pilot in Air Force history) or worked for American Airlines as a pilot. Then they’d spend the next ten minutes discussing the huge gains being made in the NASDAQ and what Schrenker would like to do with their portfolio. Nine out of ten of them were so impressed with his lies they’d transfer their holdings to Schrenker’s company.

“THE CON ARTIST has an almost uncanny ability to discover the victim’s vulnerable area and to ‘pitch the con’ to those areas,” says Charles Ford, Professor of Psychiatry at the University of Alabama, Birmingham. “[They] are suave, slick and capable; and tend to prosper through their superb knowledge of human nature.”

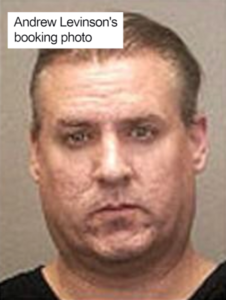

“HE’S ADMITTING TO THE LIES!” Andrew Levinson blurted out over lunch. “That’s great!”

Levinson is one of the guys I hang out with. He got 17.5 years for selling Red Bull vending machines using false earnings claims. His company raked in over $22 million from over 900 people in what’s known as a business-opportunity fraud. He’s a sharp guy, but I wouldn’t buy any vending machines from him.

We were sitting in the warehouse-size “chow hall” with Ron Wilson, a gruff old South Carolinian with a dark, dark, dark, sense of humor. Wilson’s doing 19.5 years for running a $57.4 million Ponzi scheme. He’s an interesting guy with a great head of white hair, but I wouldn’t recommend investing your retirement fund with him. Neither of these guys are soft and cuddly.

“It’s not great,” I replied. “Cheating on girlfriends and lying to clients, so what?” Schrenker wasn’t fully disclosing his discretions. He was manipulating the story.

“What do you expect? He’s a con man.”

“He’s not a con man!” I snapped. “You’re a con man. He’s a con man (I pointed at Wilson). I’m a con man. Schrenker’s a pathological liar. He has an abnormality which causes him to lie. There’s no skill in that. It’s a compulsion, some kind of cerebral dysfunction*.” What I needed was the raw unfiltered truth. Unlike my own narcissistic personality, Schrenker’s mental disorder wouldn’t allow him to disclose anything that might portray him in a negative light. He’d admit to a cunning ruse or minor fibs, but he repeatedly rebuffed any suggestion he’d knowingly engaged in criminal behavior. I, on the other hand, like most narcissists, I’m compelled to let everyone know how clever I am, despite the criminality of my actions.

“He likes to brag,” grunted Wilson. “Let ‘im know you’re impressed. Take your time. This is a guy with a mental problem and you’re a seasoned con man, he doesn’t have a chance; eventually he’ll bare his soul. He’s an egotistical prick, he can’t help himself.”

* Footnote: Over 30 percent of pseudologia fantastica pathological liars have a cerebral dysfunction and 40 percent have some type of brain abnormality.

NEVER HAD SCHRENKER’S capacity for deception paid higher dividends than with his unsuspecting clients. “His modus operandi is, he flies into your city dressed up in a thousand-dollar suit and the next thing you know [you’re moving] your money to Heritage Wealth Management,” says Joe Mazzone, one of the numerous pilots to invest with Schrenker.

“He had a way about him,” recalls David M. Smith, a retired Delta pilot and Heritage Wealth Management client. “You trusted the guy. He was very credible. He talked a great story…[but] he’s not who he seems to be.”

“WE WERE MAKING so much money,” said Schrenker, he bought a Piper Meridian for a little over $2.2 million. A sleek glossy white, midsized turbo-prop with a roomy six-seater cabin; and two Extra 300s, fully composite aerobatic aircraft with powerful engines for three quarters of a million dollars, specifically to fly in air shows. “Michelle was furious. She kept telling me, ‘You’ve got two kids and a wife!’…”

Schrenker told me, ultimately, Michelle saw it as a trade-off. She allowed him to fly around like a lunatic daredevil at international-air shows, while she got to shop for Gucci purses in Los Angeles, Prada pumps in Chicago and diamonds in New York.

“Marcus was very flashy, very showy,” said Jeff Kucic, one of Schrenker’s neighbors. “He would buzz the reservoir in that stunt plane of his and claim he’d flown all these sorties in the Air Force, but who knows with Marcus.”

In May 2000, Schrenker was performing in Nassau, Bahamas. The tourists and fans were oh-ing and ah-ing on the beach as he tried an upward tumble at 200 knots, I,000 feet above the water. He did a split-S, pulled the aircraft to the point it was facing straight down and that’s when Schrenker realized the Extra was too low. He pulled the stick back as hard as he could and suddenly, at 180 mph, the aircraft’s landing gear dug into the water. Instantly, the plane cart-wheeled and tumbled end over end. Pieces of the carbonfiber body were launched into the air and the Extra came to rest on a reef. That’s when Schrenker felt the excruciating pain in his lower back.

“I crushed my L-one through L-four vertebra.” Schrenker recalled, the surgeons rebuilt him like Steve Austin in the Six Million Dollar Man; swapping out his old parts for new stuff straight off the shelf. After extensive physical therapy Schrenker recovered with the help of oxycodone (an opiate-based narcotic). “Over time,” he told me, “I fell in absolute love with oxies.”

“WHAT PUZZLES MOST about pathological liars’ behavior, is that it is counterproductive,” says Charles Dike, Clinical Professor of Psychiatry at Yale University. “[However,] pathological liars must experience some type of satisfaction from fooling others that make them continue with this behavior.”

I ONCE ASKED SCHRENKER if Michelle ever participated in his lies. “No, not directly,” he replied. “But she never exposed me either.”

The NASDAQ index had dropped nearly 20 percent by the time Schrenker returned to work. Around that same time, he and Michelle were having dinner with several friends and someone asked if he was going to miss flying in the air show circuit. Before Schrenker knew it he was telling everyone at the table about flying A-10 Warthogs during Desert Storm. “It’s a twin-engine, straight-wing jet,” he said with pride, “designed primarily to attack tanks and armored vehicles…”

One of Michelle’s friends leaned into her and whispered, “You never told me Marc was in the Air Force…” Michelle and Schrenker’s eyes locked for a split second, she smiled out of embarrassment and said, “It was before we met.”

On their drive home, Michelle was staring out the window of their Lexus when she asked, “Why do you do that? Why tell those stories. You do it all the time. You lie.”

Schrenker was momentarily stunned. Michelle had never done more than subtly acknowledge he lied occasionally. “What does it matter, Michelle; we’re making money. So whatever I’m doing, it’s working.”

“Yeah, but those aren’t clients.” She turned toward him and said softly, “They’re my friends. Why lie to them?”

What was he supposed to say? He was a habitual, pathological liar with an excessive amount of prefrontal white matter compelling him to lie. Or maybe it was the spike in serotonin from the ego boost lying gave him. In the end, knowing the neuropsychological abnormality that contributed to his compulsion changed nothing. What mattered was—at the time—the simple act felt too good to resist.

It was the only civil conversation they’d ever had on the subject, Schrenker recalled, and it lasted less than a minute.

SEPTEMBER 11TH devastated the airline industry and Heritage Wealth Management. When the market opened they got crushed. The Dow Jones Industrial Average and the NASDAQ both dropped 15 percent the first week, losing $1.4 trillion in value. Most of Schrenker’s clients were pilots; between the dot-com bubble bursting and 9/11, they couldn’t stomach anymore losses in the market. Business dried up and employees stopped coming in. After a few months the place was empty. Schrenker filed for bankruptcy in mid 2002.

Things may have never gotten better, Schrenker told me, had he not come across Index Annuities. “They were a shitty insurance product with shitty returns and huge commissions.” If Schrenker pushed his clients to invest in Johnson & Johnson stock he might make a three percent commission, but if he convinced them to invest in an index annuity he’d make between 10.5 to 17 percent.

Unfortunately for Schrenker, after a couple years, his wealth management firm had sold index annuity products—from a handful of companies—to most of his clients. As those annuities entered their second and third year, the insurance companies dramatically reduced the dividends from 20 percent to two percent. Clients began withdrawing their money; exposing the fact that Schrenker had never disclosed the surrender fees.

“THE SKILLED CON ARTIST learns to disarm suspicions by bringing them up first, anticipating the victims own doubts,” says Charles Ford, Professor of Psychiatry. Like a psychotherapist, master con men will individualize their approach. “Similarly, the con artist will make an effort to establish a connection with the mark.”

“I NEVER LIED to my clients,” Schrenker told me; his eyes oozing innocence, “and they turned on me.” I confronted him with the overwhelming documentation I’d received that proved he’d “neglected” to disclose the annuities’ surrender fees. He denied it at first, so I changed tactics.

“Marcus,” I sighed, “it’s in my best interest to make you look good, but I can’t do that unless you trust me.” I then began laughing about my own finance company’s clients. Borrowers I’d improperly disclosed prepayment penalties to, or not at all. I began to feed Schrenker’s narcissistic personality by convincing him that we were both con men—kindred spirits—and there was no reason to lie to me. I admired his “savvy” and the “brilliance” of his schemes. The cunning way he’d done this or that. Like the Berlin Wall, Schrenker’s concrete veil of innocence crumbled. Slowly, in a disturbingly dark giddiness, he began to brag about his crimes and the victims he’d tricked into buying poor performing insurance annuities.

“Luckily,” he said, “it turned out that the problem with annuities was systemic to the industry.” Multiple companies were under attack by class-action lawsuits and there were numerous articles calling annuities “junk products.” It became easy for Schrenker to put the blame on the insurance companies. He’d tell his irate clients, “I feel as bad about this as you do” and “They lied to both of us.”

Ultimately, he convinced many of his clients to close out their annuities with one insurance company and purchase annuities with another company; thereby “churning” their money and earning himself an additional commission. “I’d then neglect to disclose the surrender fees, again,” chuckled Schrenker. “The clients I couldn’t talk into the churning scheme got so frustrated they eventually stopped calling.”

Business was booming and Schrenker’s clients didn’t have a chance; he was making a killing and he’d say anything to make a sale. According to Schrenker he once told a particularly religious client, “God personally told me buying this annuity is the right decision for you.” Another time he talked a 70-year-old retiree into purchasing $900,000 of National Western Life annuities with a 15 year maturity. However, Schrenker failed to disclose that the client wouldn’t see a penny of his investment until age 85, nor could he remove the funds unless he was willing to pay huge surrender fees.

“HE SAID [ANNUITIES] were a safe place to put money, to avoid all the world’s dangers, like terrorism,” says Michael Kinney, Heritage Wealth Management client. “In that climate, back then (after 911), you bought it. Marcus could tell dishonest untruths…over and over again and expect you to believe him. I’ve never dealt with that level of dishonesty.”

According to Joe Mazzone, another of Schrenker’s clients, “Marcus just had an explanation for everything… [However, after doing some investigating, it all turned out to be] a fabrication and a lie.”

Eventually, his deceptions were exposed, revealing not only Schrenker’s schemes, but his true nature. “We’ve learned over time that he’s a pathological liar,” says Charles Kinney (Michael Kinney’s brother), private charter pilot and Heritage Wealth Management client, “you don’t believe a single word that comes out of his mouth.”

DURING THE WRITING of Bailout. I began eating my meals with several inmates that I’d noticed working-out in the rec yard with Schrenker. I told them I was working on a true crime focusing on the events that led up to Schrenker’s attempt to fake his death.

“Shit,” grunted one inmate, a gruff 60-year-old cocaine cowboy, “the missions Schrenker flew in Iraq alone are worth writing about.” He then told me how Schrenker had confessed to flying over 80 sorties, where Schrenker had single handedly taken out 40 Republican Guard armored personnel carriers and tanks.

I blew ice tea out of my nose all over the formica table, while trying to hold back my laughter. I informed the table of convicts that Schrenker tends to exaggerate. In fact, he has never been in the military. By this point, I’d read a significant amount of material describing the causes of, and reasons for, Schrenker’s dysfunctional behavior. I’m not a psychologist, but I’d concluded, based on my research, that Schrenker was a pseudologia fantastica compulsive pathological liar. “He’s been telling that same lie, or some variation of it, for years,” I explained. It was an attempt to feel good about himself. Schrenker, like most pathological liars had told some of the same lies over and over, creating a myth of personal success to reinforce his self-esteem. “It’s an ego defense mechanism.”

“Lying piece of shit,” grumbled the cowboy, clearly irritated he’d been fooled by Schrenker. “What about NASA. He told me he worked for NASA too.”

“No,” I laughed. “He never worked for NASA.”

HERE IS WHERE SCHRENKER’S antics caught up with him. In the past, his schemes had raised the occasional red flag, but he’d always managed to lie his way out of it. However, there was one particular group of clients, I’ll call “The Client Group,” that Schrenker couldn’t baffle with his bullshit. He’d run them through his non-disclosure scam, the churning scheme and even “borrowed” funds from their accounts.

When they eventually discovered the discrepancies Schrenker tried to blame the insurance companies and accounting errors, but The Client Group wasn’t buying it. They filed a complaint with the Georgia Insurance Commissioner’s Office and within weeks Schrenker was surrounded by several bureaucratic insurance auditors, combing through client files. “We’ve got a lot of money moving from one annuity to another annuity…” growled one auditor. “It looks a lot like a churning scheme.”

Schrenker recalled after a few hours, the senior auditor suggested he was potentially facing criminal charges unless he “voluntarily surrendered” his Georgia Insurance License. Which he immediately did.

The Client Group was furious that the Georgia Insurance Commissioner’s Office hadn’t pressed criminal charges. They wanted blood. So they turned around and filed a complaint with the Kentucky Department of Insurance. Schrenker denied the allegations, but when the auditor started quoting specific violations of their state code and mentioned possible criminal charges, Schrenker offered to voluntarily surrender his Kentucky Insurance License. It had worked in Georgia.

Within weeks, he received a certified letter from the Texas Department of Insurance cancelling his license to sell insurance in their state. Days later, South Carolina inactivated his state insurance license.

Shortly after that, the Indiana Department of Insurance filed a complaint against Schrenker on behalf of The Client Group. “I wouldn’t be surprised if this becomes a criminal matter,” said the insurance regulator in charge of the investigation.

“Criminal?!” replied Schrenker. In the hope of stopping their investigation he surrendered his Indiana Insurance License.

Simultaneously, Schrenker began receiving termination letters from virtually every insurance company he’d been registered with: American General Life, Empire General Life Assurance, Jefferson Pilot Life, Lincoln Life, Mutual of Omaha, etc.

“PATHOLOGICAL LIARS seem utterly sincere about their lies,” says Dr. Bryan King, Psychiatrist at U.C.L.A. School of Medicine, “but if confronted with facts to the contrary, they will often just as sincerely reverse their story.”

MAYBE A MONTH INTO our interviews I asked Schrenker about the multiple lawsuits filed by the insurance companies.

“Lawsuits?” he replied with a blank look of bewilderment. “I was never sued…” Are you certain, I asked, that he nor Heritage Wealth Management was ever sued. Schrenker sighed as if the questions were preposterous. “I think I’d know if we’d been sued.”

Then, I pulled out a copy of a lawsuit filed in early 2007 by OM Financial Life for the return of $1.5 million in commissions from the stack of documents Ross had sent me over the previous weeks; and I showed it to Schrenker. “What the…” he stammered. “Where’d you get this?” I told him to stop lying and asked, if there were any other lawsuits that he knew of. “No,” he admitted while thumbing through the papers. “No, this is the only one.”

I slipped out a second suit filed by National Western Life for $1.4 million and held the copies up to Schrenker’s face. He blurted out, “Now, I see why you’re confused” and chuckled, as if it were all a stupid mistake on my part.

“I’m confused,” I said, “because you’re lying to me!” I patted the stack of documents before us and asked if there were any other lawsuits. Schrenker glanced at the pile of paperwork I’d accumulated; and for the first time I could tell he was questioning whether he should be talking to me.

“Of course we were sued,” he admitted. “Wealth management firms are sued all the time—”

I didn’t point out that 30 seconds earlier he’d denied the suits existed. It wouldn’t have gotten me very far. I was used to him flip flopping.

THE BUBBLE HAD BURST by the end of 2007 and the Dow Jones Industrial Average Index was in free-fall. Between Lehman Brothers, Bear Stearns, Merrill Lynch, Goldman Sachs and Morgan Stanley alone, there were reported losses of over $4.1 trillion. Roughly 30 percent of the U.S. GDP for 2007 was gone.

By the beginning of 2008 new business slowed to a trickle. The Client Group had shut Schrenker down in the insurance industry, but he wasn’t finished. More and more indicators were showing the U.S. economy was in real trouble. The one consistently rising hard currency at the time was the Euro—up 60 percent since its introduction in 2002. So, according to Schrenker, he began actively contacting clients in an attempt to put together a legitimate currency fund. However, the way Schrenker tells it, by the time the checks started coming in, he and Michelle were so in debt, it quickly mutated into a Ponzi scheme.

“DON’T EXPECT REMORSE. Pathological liars look at a situation from their own perspective,” says Robert Feldman, PhD, Professor of Psychological and Brain Science at the University of Massachusetts. “They have no regard for…what might happen as a result of their lies.”

“YOU HAVE TO UNDERSTAND these were rich, rich people,” said Schrenker. “They weren’t going to miss the money.” Unfortunately, based on his indictment and the victims statements, it appeared to me that the investors were not rich. They were middle-class citizens who had worked their entire lives for what they had and Schrenker was fleecing them like a common thief. A pickpocket in an Armani suit.

The scheme worked for two reasons: one was Schrenker’s access to Fidelity’s website, which allowed him to maintain his clients’ account information. Secondly, his clients trusted him. Take Robert Askins, a retired Delta Airlines pilot. When Schrenker mentioned the Euro Fund to Askins, he didn’t hesitate to invest $100,000.

Sometimes—if Schrenker got into a jam—he wouldn’t even ask for the “investment,” he’d just take it. He recalled being caught by Tania and John Winfield after removing $10,000 from their account. Tania called and asked about the wire-transfer before he could replace it. Schrenker’s adrenalin spiked, but he casually told her, “John authorized me to invest ten thousand dollars in Euros.”

They hung up, but a minute later Tania called back. “Marc!” she snapped, “John said he never authorized any wire-transfer.”

Schrenker feigned confusion, placed her on hold and wondered if Michelle would bring the kids to see him in prison. Probably not. He then hit the hold button, came back on the line and blamed the misappropriated funds on his secretary. “Look, I’ll wire the ten thousand back, along with your gains—should be around eighteen hundred dollars—”

“Eighteen hundred?” gasped Tania. “In less than a month?”

“Well, yeah…the Dollar’s in free-fall.” He paused to let the imaginary gains sink in and continued with, “It’ll be back in your account tomorrow—”

“No!” she yelped. “I mean, if it’s doing that well, leave it.”

A month later, Tania stopped by the office with a check for roughly $45,000 and asked him to invest it in Euros. Schrenker admitted, at the time, he didn’t even need the money, but he’d been lying for so long, that honesty felt unnatural—almost abnormal. As a result, dishonesty, had become instinctual, natural, and yes, pathological. So when she handed him the check, “I took it.”

I asked Schrenker about the $30,000 his aunt had given him. Money she thought she was investing in Euros. His eyes darted to the pile of documents sitting on the table beside me and I knew he didn’t want to answer. There was a long silence where we both wonder what lie he’d tell me. Instead, Schrenker blurted out, “What choice did I have? You’ve gotta steal from your friends and family,” he shrugged, “your enemies won’t do business with you.”

DURING THE SAME TIME period, Schrenker began seeing Kelly Baker—a younger version of the actress, Sandra Bullock—whom he had been seriously flirting with for around six months. Eventually, he told her, “Kelly, you know I’m married, right?” She shot back, “I’m discrete.”

He bought Kelly stylish Louis Vuitton handbags and expensive watches. He moved her into a condo down the street from his and Michelle’s house. It didn’t take long for his wife to figure out he was having an affair. Michelle tried everything from a blitzkrieg-style marriage intervention to counseling, but Schrenker wouldn’t stop seeing Kelly. He just denied the relationship existed.

It was only a matter of time before his deceptions caught up with him; and Schrenker was coping with sex, alcohol and opiates. He had prescriptions from doctors in Indiana, Georgia, Florida, and even they weren’t enough.

Despite the turmoil of the economy, Schrenker’s finances, his drug use and the deterioration of his marriage, by all accounts, he and Michelle appeared to be an attractive, happy and successful couple. Which explains why in late August, the marketing director for Tom Wood Lexus—the local Lexus dealer—asked if they would do a photo shoot for the dealership. A professional photographer snapped around a hundred shots of the couple at the airport; while leaning against their glossy Lexuses with Marcus’ sleek Meridian in the background. Sporting Armani and flashing their pearly whites, they looked like a couple of runway models—synthetically perfect and artificially happy.

THERE WAS A SEMI-NAKED photo going around the prison. A gorgeous brunette, seductively, peering back at the photographer while standing in front of a pedestal sink; wearing nothing but a G-string and high-heels. Federal inmates aren’t allowed pornography; candid soft-core semi-nudity is as close as we can get.

The inmate selling them had a dozen copies of the glossy pics. “For two dollars in commissary she can be yours,” was his pitch.

My cellie had a copy of the stilettoed vixen—pinned to the corkboard in our cell—next to the photo of his elderly mother. Two other guys in the housing unit had the brunette taped to their lockers.

While sitting at our next meeting in the library—maybe a week after first seeing the photo—Schrenker told me, “I got a letter from Kelly. She heard I’m getting out soon.” He began digging through his gym bag looking for something. Then he turned and handed me a glossy photo. “She mailed me a picture.”

It was the brunette-vixen being sold around the prison. Schrenker didn’t know that I’d already received a picture of Kelly taken from a blog; and she looked nothing like the girl I was holding. But I didn’t confront him.

The lie was so disturbing, so pathetic, all I could muster was a polite smile and a grunt, “Huh.”

“I took that picture when we were in Miami,” he said. “Can you believe she sent that to me through the prison mail?”

“No,” I replied. “I can’t.”

“COMPULSIVE LIARS have a need to embellish. They tell the stories they think you want to hear,” says Paul Ekman, PhD, Professor of Psychology at the University of California. “[They] may even continue to lie when they know you know they’re lying.”

THE AVERAGE U.S. HOUSING price had dropped 20 percent by September 2008. Ten percent of all U.S. mortgages were in foreclosure and over 100 lenders had gone bankrupt.

Treasury Secretary Henry Paulsen and Federal Reserve Chairman Ben Bernanke proposed a $700 billion bailout to stabilize the economy. “If we don’t do this now,” said Bernanke, “we may not have an economy on Monday.” The Troubled Asset Relief Program was signed into law by President George W. Bush in October 2008.

Slightly over a month later, in early December, Bernie Madoff was arrested on securities fraud; as a result of his wealth management firm running one of the largest Ponzi schemes in history—$65 billion. Schrenker told me Madoff’s arrest sent a wave of panic through the financial community. Clients that had never so much as requested a statement before were suddenly demanding, “Where exactly are my assets” and asking “Are my investments secure?”

A week or two into the chaos one of Schrenker’s financial planners stepped into his office and said, “I’ve got a client on the phone that wants to transfer his account . . . Do we have something called the Fidelity Euro Fund?” He looked at his thieving, adulterous, pathological-lying, pill-head boss and waited for an answer, but Schrenker didn’t have one. “Marc?”

“It doesn’t exist,” Schrenker responded, locking eyes with the planner. He remembered unscrewing the top of an OxyContin bottle, tapping out a couple pills and slipping them into his mouth.

“So where are the funds?”

“Gone,” admitted Schrenker. The planner went straight back to his desk and called the Indiana Department of Securities.

“[T]HE DEGREE OF CONSCIOUSNESS and aforethought that was required to carry out Cox’s scheme was stunning,” says Timothy C. Batten, Sr., U.S. District Judge. “It required a commitment level that reflects either a sociopathic disregard for others or something else that is profoundly wrong.”

I DON’T GET A LOT OF VISITS. My mom and a couple old friends, then there’s Ross. We were sitting in the visitation room sometime in January 2014, surrounded by nearly 100 other inmates and their guests. I went over my most recent victories, regarding Schrenker’s story and Ross did a half eye roll. He’d already told me he wasn’t wasting anymore time doing research on “the liar.”

“I just need a couple more things.” One of them being a transcript from a civil lawsuit. “Schrenker’s whole world was falling apart. The authorities were closing in on him.” According to Schrenker he’d stopped paying his bills and the lawsuits were piling up. “During the deposition of one particular suit, Schrenker told the plaintiff’s lawyer that he could no longer work fulltime due to his multiple sclerosis…”

“No,” said Ross, “he didn’t.”

“Of course he did. That’s what he does.” The problem was the deposition had been video taped and, as an inmate, I don’t have access to a video player. Therefore, I needed Ross to purchase the video and hire a court reporter to create a transcript for me. “That shouldn’t cost more than fifteen hundred dollars.”

“Absolutely not!” he barked. “You’re outta your mind, brother. I’m not wasting anymore time or money on this guy. He’s a scumbag.”

“I’m a scumbag.”

“Yeah, but you’re a likable scumbag; he’s a sociopath.”

“Ross, I’m fairly certain my judge called me a sociopath; it’s still a good story. More so because of his pathology.”

“Does this guy have any idea of what you’re doing?”

“Of course not, I’m manipulating him. He thinks he’s confiding in a peer. He thinks I admire him.” Half the stories I was telling Schrenker about myself were altered in order to induce a similar story regarding a particular fraud I already knew he’d committed. “I’m conning the truth out of ‘im.”

“You need to walk away from this little project,” hissed Ross. But I couldn’t walk away. Schrenker’s life of lies were crumbling all around him and he was about to implode.

THE MORNING OF THE RAID, December 31, Schrenker recalled he and Kelly were on a mini-vacation, lying on the beach outside their hotel in sunny Florida. “It was supposed to be a relaxing getaway,” said Schrenker. “But by the time I got back to Minneapolis the Indiana State Police and Investigators from the Indiana Department of Securities had seized all my records.” In addition, Michelle had emptied out Schrenker’s bank account, changed the locks to their house and filed for divorce. “Three days later, my stepfather died . . .”

On January 9, 2009, Michelle and Schrenker were standing at the grave site, while mourners wept and sobbed. Between the lawsuits, several bad trades and the Ponzi scheme proceeds, Schrenker owed roughly $6 million. There was some cash and a nice little stash of gold in his basement safe, but that was it. No charges had been filed yet, still, he knew they would be. He knew he was facing at least a decade in prison. Standing there by his estranged wife, all he could think about was, any day now he’d be arrested. The thought of what his kids would think of him was so constant by that point, even the alcohol and the opiates weren’t enough to wash them away.

Staring at the coffin, all Schrenker wanted was to jump in the box with his stepfather and die. Escape. That’s when it hit him. He turned to Michelle and said, “I’m gonna take out the Meridian, set the auto pilot, fake an accident and bailout. Let it crash into the ocean . . . We’ve got the life insurance policies.”

Michelle took a deep breath, let it out slowly, and said, “So do it.” According to Schrenker, she didn’t even try and talk him out of it. Who could blame her.

DESPITE REPEATEDLY ASKING SCHRENKER, he never could come up with a single shred of evidence proving the life insurance policies existed—totaling $11.1 million between John Hancock, Northwestern and First Penn Pacific. No matter how much I pressed Schrenker he refused to admit they were a fabrication.

Eventually, I came to understand—in Schrenker’s mind—the money somehow justified abandoning his wife and kids. “I wouldn’t leave them with nothing,” he said when I confronted him about the lack of proof.

“What kind of person do you think I am?”

By this juncture, I’d peeked behind the curtain at the Great Oz. I’d seen the truly disturbed individual working the levers and I knew he couldn’t admit there were no policies.

“THE NARCISSIST’S PERSONALITY is tied to wealth and power,” according to Donald Davidoff, Harvard University Neuropsychologist, “[when] disgraced, the experience produces a dissolution of their personality. They run because of a loss of self.”

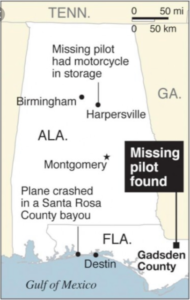

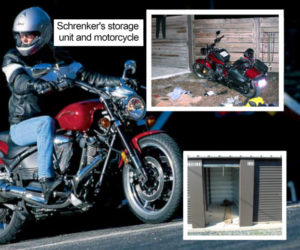

WITHIN 24 HOURS of his stepfather’s funeral, Schrenker had towed his red Yamaha Prostar motorcycle to a storage facility in Birmingham, Alabama. He found the perfect place to jump and headed back to Indiana.

On January 11, 2009, he boarded his Piper Meridian with a stunt parachute—a one-time-use-chute with no backup. According to Schrenker, he also had a canvas bag containing 50 pounds of gold coins. He quickly programmed the autopilot for a rapid descent to 10,000 feet where the aircraft would level off, fly out over the Gulf of Mexico, run out of fuel and plunge into the ocean.

Minutes later—at approximately 6:45 p.m.—the Piper roared down the runway at Anderson Municipal Airport, Indianapolis, and climbed to a cruising altitude of 24,000 feet. Approximately an hour later as Schrenker was approaching his jump site, while cutting through the freezing Alabama air at 300 mph, he shouted, “Four-two-eight-charlie!” into his headset. “Atlanta Center! This is an emergency! I’m experiencing severe turbulence and my windshield is spider cracking . . . Windshield has failed!”

Over 200 miles away in Peachtree City, Georgia, half a dozen Air Traffic Controllers immediately scrambled around the FAA air route traffic control center, desperately rerouting commercial air traffic.

“Four-two-eight-delta-charlie,” squawked the radio, “descend immediately! Descend immediately!” Schrenker flipped on the autopilot, the Piper nosed over violently and began the emergency descent.

“Atlanta Center, windshield has failed! I’m bleeding profusely,” he shouted; then wrapped his headset around the yoke and crawled from the cockpit into the seating area. He slipped on the parachute, as the aircraft plummeted and double-tied the bag of gold to his ankle.

The FAA immediately notified the Coast Guard and requested the Air Force scramble fighters to intercept the Meridian. Within minutes, two F-15 Eagles lifted off the asphalt in New Orleans Naval Air Station. Tucked underneath their battleship grey wings were four air-to-air AIM-7F Sparrow Missiles. Seconds later the Eagles’ pilots slammed the throttles forward and the twin-engined fighters went supersonic—screaming toward the distressed Meridian.

Schrenker could still hear the FAA controller screaming, “Descend immediately!” from the cockpit, when he slipped a couple oxycodone into his mouth, chewed them up and swallowed the bitter fragments. Somewhere around 18,000* feet he grabbed the aluminum door handle with both hands. For a split second he thought about his soon-to-be “widowed” wife and the three beautiful children he was abandoning. He twisted the handle with everything he had.

The hull pins retracted, the atmospheric seal broke, the decompression simultaneously blasted the door, along with Schrenker, out of the cabin. He slammed into the door and the clamshell-stairs snagged one of the parachute’s nylon vest straps, slung him around and smashed him into the side of the aircraft.

Between the 300 mph wind and the pitching and yawing of the plane, Schrenker was being repeatedly bashed into the aluminum fuselage of the Piper. Just when he thought, This can’t get any worse, the parachute deployed and was instantly shredded by the hurricane strength relative wind.

Suddenly, the plane pitched upward and his vest’s nylon strap snapped, sending Schrenker tumbling through the air with the useless tattered remnants of the parachute trailing above him.

* Footnote: In contradiction to Schrenker’s account, FlightAware’s Live Flight tracker, noted at 8:23 p.m., just south of Huntsville, AL, the Meridian begin descending at 2,000 ft per minute. Northeast of Birmingham, AL, the aircraft leveled off. Somewhere between 3,900 and 4,000 ft, Schrenker made the bogus distress call to air traffic control and then set the auto pilot.

The Meridian disappeared into the distance as the gold dragged him toward the ground and his inevitable death. All he could hear was the rushing wind and the flapping of his tattered parachute. Surviving never crossed his mind. On the upside, the oxycodone was kicking in.

Schrenker caught the reflection of the moon on the Coosa River as it snaked through the Alabama hills just before he hit the treetops. He shot through the 100-foot tall oaks and pines at a five degree angle—snapping branches and twigs. Simultaneously, the parachute’s cords caught in the branches and slowed Schrenker’s descent slightly; yanking the nylon-harness and cutting into his ribs and crotch. Then, he hit the cold water, only feet from the tree-line.

“That’s when I lost my testicle,” recalled Schrenker. Excuse me, I replied. Did you say testicle? “Yeah” he continued. “My left nut was severed by the nylon-crotch-strap.” According to Schrenker, he looked for the little fella, but it was nowhere to be found. Not in the jumpsuit or his jeans. He also told me he nearly froze to death trying to escape the river and had to cut the drop-line connected to the gold—leaving it on the bottom of the river.

DURING LUNCH THE NEXT DAY, in the chow hall, I informed Levinson and Wilson of the bizarre turn of events. The severed testicle.

“So what you’re saying,” said Wilson, “is this guy’s pulling to the left? He’s asymmetrical? Unbalanced? Light in the britches?”

“The unbalanced part I’m sure of.”

Ignoring Wilson, Levinson asked, “What happened to the nut? Did the fish eat it?”

“No the fish didn’t—you’re missing the point!” I barked. “He’s lying.”

Levinson and Wilson glanced at one another. Then Levinson said, “You wanna do this on the streets. You wanna be a true crime writer, a journalist? If that’s the case,” Levinson told me I was going to have to “man up” and take Schrenker into a shower-stall and ask him to show me the scrotum. Levinson laughed, “Tell ‘im to stretch it out like a batwing.”

“It ain’t gonna happen!” I snapped.

Wilson interjected, “How elaborate is his testicle story?”

“He told me he suffers from low T (testosterone) and he takes medication,” I replied. “It’s pretty elaborate.”

Wilson kneaded his fingers into his bulldog face and growled, “What kind ‘a man tells another man he’s got low testosterone?”

JUST BEFORE TEN O’CLOCK the Air Force fighter pilots noticed the Meridian was decelerating and losing altitude north of the Florida state line. Between the low altitude and the drag caused by the open door, the Piper had exhausted its fuel supply. At 10:12 p.m., the aircraft came soaring out of the moonlit sky and slammed down into a swampy wooded area of the Blackwater River in east Milton, Florida—a few miles short of the Gulf of Mexico.

Sergeant Scott Haines with the Santa Rosa County Sheriff’s Office arrived first to the accident scene. “When we got [to the crash site] with the dogs, we didn’t locate any blood. We didn’t locate any imploded windshield,” said Haines, “That’s when we realized something was definitely not right.”

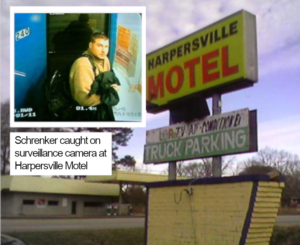

After escaping the river and spending nearly two hours pushing his way through the woods, with blood running down his leg from his torn scrotum, Schrenker found himself limping across the asphalt parking lot of a Kangaroo gas station; when two Childersburg Police Officers pulled up in their cruisers.

“You got some identification?” asked the taller of the two, as he exited his vehicle. Schrenker handed him his Indiana Driver’s License and he knew it was over.

Despite conflicting accounts, Schrenker insists the incident played out in the following manner; while one officer ran his name, the second slowly ran the beam of his Maglite over Schrenker’s black jumpsuit. “What’re you supposed to be,” he asked, in a thick southern drawl, “some kind ‘a ninja?”

“I’m a pilot,” Schrenker replied. Then he looked up into the darkness and said, “My plane malfunctioned and the door came open and . . . the decompression blew me out.”

The officers didn’t believe his story. They asked Schrenker what type of drugs he was on and after a brief discussion about his oxycodone prescription, the officers dropped him off at a 1950s Bates-style motel—right down the street from his storage unit.

Schrenker was retrieving his camping gear and motorcycle at approximately the same time the Childersburg Police Department received a call notifying them the U.S. Marshals were looking for a missing pilot.

Shortly after the call, Schrenker was riding back to the motel when he noticed several police cruisers racing into the parking lot. He casually drove by as the officers swarmed into the leasing office.

By the time he setup camp at the Hastings Family KOA Campgrounds—the following morning—the media had already pounced on the story: Financial Advisor Under Investigation For Securities Fraud Fakes His Own Death. Schrenker knew it was over. That’s when he started thinking about suicide.

NARCISSISTIC PATHOLOGICAL LIARS don’t kill themselves. Their egos won’t allow it. So, I suggested, suicide, seemed out of character for him. After an eerie silence, Schrenker grinned. “I said ‘I started thinking about suicide,’ not killing myself,” he replied. “I’d screwed up so bad, I thought it might get me some sympathy; maybe a reduced sentence.”

Schrenker told me he swallowed a handful of oxycodone with the last of his beer and fired off an email to Tom Brit, an acquaintance that ran Schrenker’s neighborhood newsletter. Even in Schrenker’s darkest hour, he kept lying: “[Tom], I hope you’ll set the record straight . . .” Even after reading that the authorities had found the plane with the windshield intact he wrote, “The accident last night was caused by the pilot side window imploding . . . When the cockpit depressurized it blew out the back door . . . I bled a hell of a lot.” He alluded to running out of oxygen and experienced hypoxia—a condition resulting from lack of oxygen—”caus[ing] people to make terrible decisions” and he wrote that the securities fraud investigation was all a misunderstanding. Schrenker just couldn’t admit he’d duped his clients out of their money. He blamed it all on bad investments. “I would never purposely abandon an aircraft and endanger other lives . . . I never meant to hurt anyone.” He ended it with “By the time you read this I’ll be gone.”

Knowing Brit checked his email compulsively, Schrenker was certain he would contact the authorities; they’d track the email back to KOA and “save” his life. That was the plan—the new plan.

He then dragged the blade of his hunting knife against his wrist. Blood gushed out and began puddling at the bottom of the nylon tent.

Schrenker told me an elaborate Hollywood-version of his capture, complete with a team of cyber-cops tracking down his emails point of origin, the re-tasking of a military satellite and helicopters. But according to my research, he simply didn’t pay his campsite rental fee, which caused the owner, Troy Hastings, to stop by the site. Hastings noticed the blood and called the Gadsden Sheriff’s Office.

Just before ten o’clock, on January 13, over two dozen marshals and deputies approached the tent. They found Schrenker passed out, lying in a pool of blood and pills. Ashen with virtually no pulse.

“Blood. Lots of blood,” said Carline Hastings. “Right around the time the ambulance was pulling in, [one of the marshals] walked over to say, ‘Yeah, he slit his wrist,’ and they didn’t think he’d make it.”

Schrenker had almost died trying to fake his own suicide. He was medivac’d to Tallahassee Memorial Hospital where the doctors saved his life.

The next few weeks were a jumble of paparazzi, county jails and court appearances. Schrenker told me at one point, Michelle came to see him at the Miami Federal Detention Center. He tried to apologize to her. She slipped her soft, silky hand into his palm and twisted it to inspect the pink scar on Schrenker’s wrist. Michelle shook her head.

“You idiot,” she hissed while running a nail up his forearm—from his palm to his bicep. “You cut up not across. Next time try a gun.” Apparently, reconciliation wasn’t an option.

Shortly after that, Schrenker pled guilty and was sentenced to 51 months in federal court for willful destruction of an aircraft and transmitting a false distress message. Over a year later he was sentenced in the state of Indiana to twenty years—ten years of which was suspended—on securities fraud. Between the two sentences, Schrenker received over 14 years. However, with time off for good behavior and halfway house, he’d serve less than six years.

“YOU MADE ME SOUND like some kind of criminal,” Schrenker whined once he read the completed manuscript. “Matt, if this gets out people will think I’m a…a liar.”

It wasn’t the first time he’d contradicted himself. Over the months I’d caught Schrenker in so many lies I’d come to the conclusion it wasn’t worth confronting him.

Regardless, I tried to explain that brutal honesty was his only hope of redemption. Over the next few weeks, I tried to work with Schrenker, to make reasonable changes, but short of removing all references of his pathological lying and crimes, he refused to be satisfied. Ultimately, I realized that Schrenker had originally expected me to write an account of his story that would exonerate him. Once he realized I was unwilling to do that, he stopped cooperating.

I told him it didn’t matter, I already had the story. “I’ll publish it without you.”

He chuckled at this. “You’re just some guy in prison,” Schrenker scoffed. “No one’s going to publish anything you write,” and he walked off.

IN SEPTEMBER 2014 Schrenker left for a halfway house in Pensacola, Florida. During lunch that day Levinson asked what I planned to do with the manuscript. “The problem is, Schrenker was right,” I admitted. “No one’s gonna publish it, I’m just some guy in prison.”

Levinson nodded his understanding. Maybe a minute later he said, “You know what’s a good story? This. You being in prison with Schrenker, conning the truth out of ‘im. That’s a good story.”

I mulled it over for a couple seconds and added, “It takes a con man to get the truth out of a pathological liar. It’s got an interesting twist.”

I CAN’T TELL YOU that 100 percent of Schrenker’s story is accurate. His version of the truth is mercurial at best. However, based on state and federal court documents, transcripts, investigative reports, victim statements, emails, etc., I believe the bulk of the story is true. Still, if I had to put money on it, I’d say Schrenker still has two balls.