THE SLEEK CURVED BODY of the gulfstream G-V cut through the thin Nevada air at nearly six hundred miles per hour and 43,000 feet. Tonight, however, the glossy white private jet’s typical cargo of corporate executives and Hollywood royalty had been replaced by a gifted crook and his female companion. A modern day paperhanger—and a major problem for the U.S. Secret Service’s war on cybercrime.

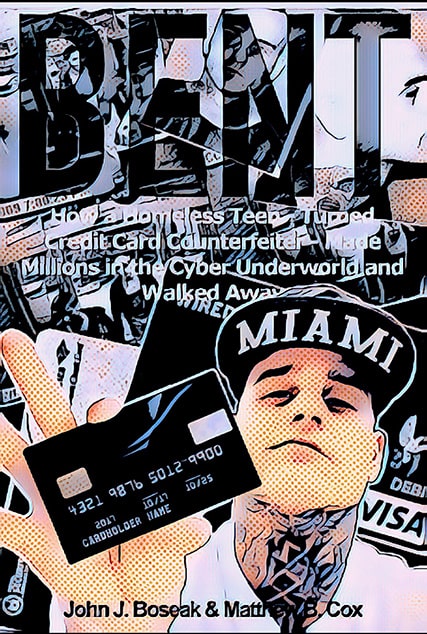

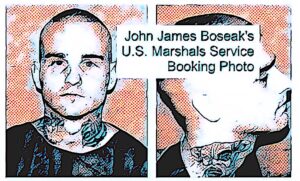

At twenty-six-years-old John Boseak was the most prolific manufacturer of counterfeit plastics in the international cybercrime industry. Visa, MasterCard, American Express… state IDs and driver’s licenses, you name it—he could make it. Boseak had a savant-like ability to circumvent bank security and stay one step ahead of federal law enforcement. However, there had been the occasional need to slip through a side-exit or rear-window. No one’s perfect.

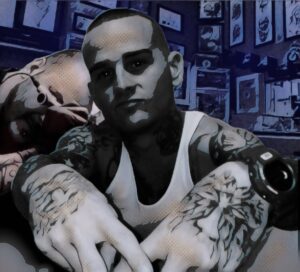

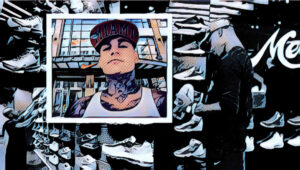

His blond cropped hair, fair skin, and blue eyes were strictly Scandinavian; a Dolce & Gabbana button-down and Armani slacks concealed the edgy tattooed images of Nordic deities and Asian mythological creatures that covered most of his lean, five-foot seven-inch frame. But nothing could hide the snarling faces of Odin and Thor that covered Boseak’s neck. The gods of war sat high above his silk white collar. He could’ve passed for a hardened criminal, had it not been for his baby-face good looks and stylish apparel.

The exquisite raven-haired girl sleeping in the recliner beside Boseak stirred. She woke with an exaggerated yawn exposing a tongue stud. White trash beautiful with a splash of alternative sexy. The girl looked up at him, smiled, and asked, “What’s your name again?”

Boseak honestly couldn’t recall which of his numerous alias names he’d given her. “Does it matter?” he replied, as his fingers danced across the face of his smartphone, connecting to UPS’s tracking page. There were five hundred imitation Visa and MasterCards en route to Odessa, Ukraine, and another three hundred cards were headed to Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. Nothing had been seized by U.S. Customs… today.

“Seriously,” she said, “are you someone famous?”

“Hardly,” he snorted, while tapping a dozen keys; logging onto Western Union’s website and checking the activity of several accounts. Multiple wires had arrived over the last few hours—totaling over $100,000. Not bad, he thought, for a guy who grew-up homeless on the streets of Miami.

The girl peered out the window at the lights of Sin City. “You sure look like someone that should be famous,” she giggled. “Like a rock star or someone.”

“I’m nobody,” he replied. Boseak hadn’t invented the underground world of cybercrime. He was just one of the few cyber scammers clever enough to crack the banking system, cunning enough to consistently slip through the authorities’ fingers and shrewd enough to make millions in the process.

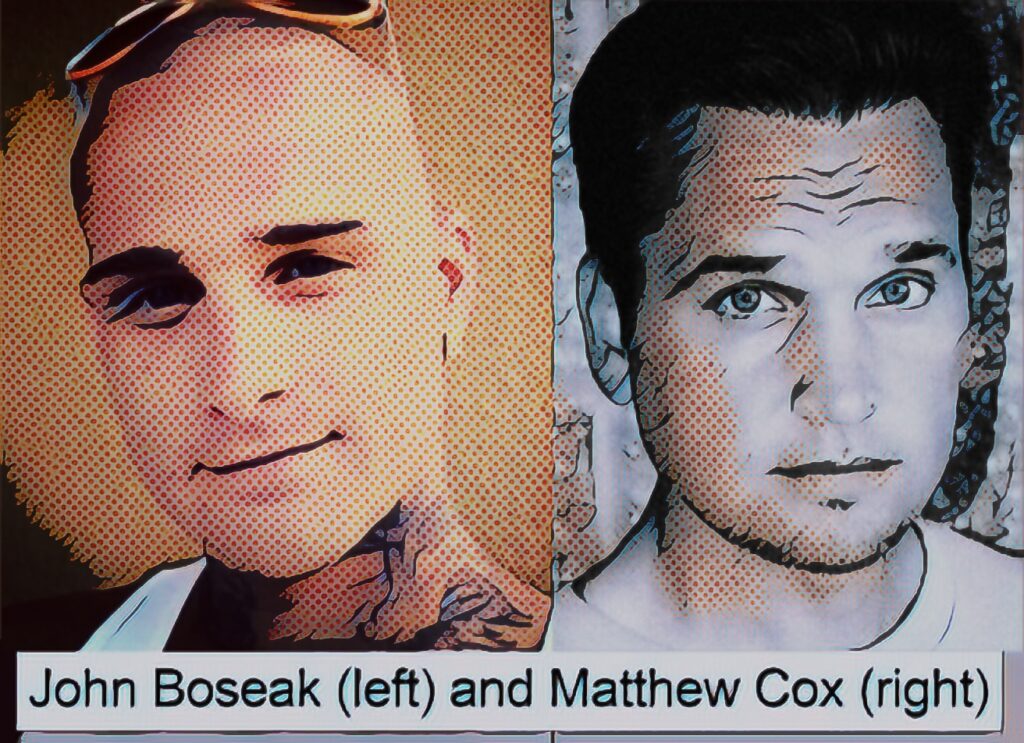

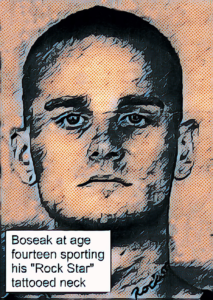

BOSEAK HAD ALWAYS wanted to be a rock star, he told me, during one of our many interviews regarding his story. He’d taken it so seriously, that as a teen, Boseak had “rock star” tattooed across his neck. “Unfortunately,” he says with a chuckle, “that’s not where my talents lie.”

He’s well spoken and polite. Quiet and unobtrusive. Unlike most of the tattooed thuggish inmates we’re surrounded by at the Federal Correctional Complex in Coleman, Florida. That’s where I met John Boseak, standing in line in the prison cafeteria. Holding our trays waiting to be served slop that the correction officers keep telling us is barbeque pork—I have my doubts.

I should tell you I’m an inmate serving nineteen and a half years for a major bank fraud; and I’m one hundred percent guilty. Some inmates do their time in the rec yard—walking the track and doing pushups. Others learn to play an instrument. I write true crime/memoirs. As a result, I hear a lot of stories. Some interest me and some don’t. But when I hear one as brazen as Boseak’s… I had to look into it.

So I ordered Boseak’s Freedom Of Information Act; reviewed the investigative reports, the indictments, the court transcripts, and numerous miscellaneous law enforcement documents—all of which corroborate his amazing story. I’m intrigued, and I agree to help write, Bent, Boseak’s autobiography. However, despite the documentation, what follows is largely a tale straight from the counterfeiter himself—an admitted scammer and conman.

At the age of seven, Boseak’s single mother moved him and his younger brother, Christopher, from Michigan to South Florida. The way Boseak tells it, Kendall—just south of Miami’s city limits—was a quiet little suburb made up of new homes with in-ground-pools and minivans; packed full of middle-class families with middle management dads and soccer moms, happily raising 2.3 average kids. “We… well… I never fit in there,” he admits.

While other kids’ parents were opening college funds, the Boseak brothers’ parents were arguing over child support payments. When other kids were writing letters to Santa Claus, they were signing up for the Toys For Tots program. While other kids laid in bed at night, dreaming about their futures, the Boseak brothers wondered where their next meal would come from.

Their mother worked full-time plus overtime, says Boseak. “We were completely unsupervised. It was inevitable I’d get in trouble.”

BOSEAK’S CRIMINAL CAREER started with Grand Theft Auto. The game was released on Sony Playstation in late 1997. Boseak and his gang of twelve-year-old friends spent most of their time sitting in front of the TV, stealing cars and out running the cops during high-speed pursuits through Vice City.

“I’m certain that’s what gave me the idea to start stealing bikes,” he recalls.

After one of his buddies bragged about stealing a bike and throwing it in the canal behind his house. Boseak suggested they steal a bike and sell it.

Billy, the alpha dog of the group, barked, “You won’t do it; you’re too scared.”

Boseak grabbed a set of bolt cutters, stole a bike from the mall, and sold it to a pawnshop. “The owner told me ‘If you come across anymore of these… bring ’em in’ and he gave me a wink. I remember feeling like I’d gotten a nanosecond glimpse of some criminal underworld.” In that fraction of a second… Boseak felt like he belonged.

Over the course of several months he stole over sixty-five bikes. He was eventually nabbed, after a Mission Impossible style caper where Boseak and a friend broke into Miami-McArthur Middle School’s bike pen, stealing fifteen bicycles. He was charged with grand theft.

Shortly after completing his probation Boseak was arrested for shoplifting tennis shoes in a JC Penny. “I was a pretty rotten kid,” says Boseak.

Eventually he ended up in the Teen Ranch Reform School. Three months into his sentence Boseak and another juvenile delinquent “escaped.”

The teen fugitives spent the next several months sleeping at friends’ houses and panhandling outside fast food restaurants. According to Boseak, couples make the best marks. He’d make puppy-dog eyes and plead, “Sir, can you spare some change?” or “Ma’am, I’m so hungry… Can you please buy me a ninety-nine cent cheeseburger?”

Men would stuff dollar bills into his outstretched hand, says Boseak, “and women would ask, ‘Sweetie, is your home-life really so bad you have to live on the street?’ I’d sniffle back some crocodile tears and tell them ‘My mom’s hooked on crack and my step-daddy… he touches me.’ We made out like bandits.”

BY THE TIME BOSEAK was recaptured in early 1999, his mother had moved back to Detroit with his younger brother, and the Juvenile Assistance Center couldn’t locate her. The fourteen-year-old was made a Ward of the State and placed in a juvenile homeless facility. “It was a horrible place… a warehouse,” Boseak muses. Something about the memory unsettles him, but all he’ll say is—”I ran away within a week.”

Months later he located his mother in Detroit. “I called her and explained the situation. I told her ‘I need you to come down here and get me… Tell the state I’m not their property’…” Unfortunately, when it came to her eldest son his mother was void of parental instinct. “She told me ‘you haven’t listened to me since the day you were born… You’re on your own kiddo.'”

HE BECAME PART OF the teen homeless subculture; thousands of “street kids” that live day to day by their wits and resourcefulness. According to Boseak, a typical day consisted of panhandling or dumpster diving. Sometimes they would walk the beaches and ask tourists if they had any “loose change” or “an extra cigarette.” On Sundays, Tuesdays, and Thursdays, they’d hit the soup kitchens at Commercial Boulevard and 6th Street. Then there was 7-Eleven, “every two weeks they’d restock their sandwiches, and throw out the old ones at midnight,” recalls Boseak. “Me and the gang were always in the alley waiting next to the dumpsters.”

At night, some of the kids would crash at friends’, while others slept in abandoned houses or buildings. Everyone had a secret cubbyhole. Boseak’s was the maintenance closet on the roof of a four-story mixed-use building in South Beach. “I’d sneak up to the roof, curl-up in my sleeping bag, and drift off to the sound of the humming rooftop air conditioners…” At the time, Boseak thought he had it made. “Hanging out with my friends on the beach, getting stoned, and staying out all night. No parents and no rules. I can’t say I missed having a normal family life. You can’t miss what you never had.”

There was always the risk of being arrested for trespassing, shoplifting… Weeks before Boseak started Garden High School, he and a friend were panhandling in front of a Taco Bell and getting nowhere. His stomach started growling, so he strolled into Super Walmart. “I snatched a steaming hot, pre-cooked, glazed chicken off the shelf,” says Boseak. He rushed into the large public restroom, passed several urinals and five toilet-stalls, and entered the last stall. “I was in the middle of devouring the chicken, when the manager banged on the outside of the door. He started yelling, ‘Open up kid! I know you’re in there!’ and I froze.”

His fingers were dripping with grease and his cheeks were stuffed full of white meat—a chipmunk perched on a porcelain throne. He dropped to the tile and slithered through the ten-inch gap at the bottom of the stall-divider as the manager screamed about “calling the cops!”

With the manager’s back to him, Boseak slinked out of the restroom and scurried through the grocery store.

“That was my life.”

BOSEAK BECAME INTERESTED in graphic design in early 2001, after meeting Mr. Johnson; a software engineer that volunteered at one of the homeless shelters. He saw a spark in the teen, Boseak didn’t know existed. Johnson made some calls to a friend at Miami Technical Institute and a week later the sixteen-year-old was enrolled in Microsoft Office Suite, Basic Web Design, and several other graphic design classes.

“The instructors told me I had ‘the patience of an artist’ and ‘an aptitude for problem solving,'” he says. “It was the first time in my life adults were telling me I was ‘talented’ and ‘gifted.’ Still… I had nothing in my pocket.”

The teen decided to apply his new skills to his current problem. His first true forgeries were McDonalds and Burger King gift certificates. However, he quickly switched to a newer version of the classic “ring drop.”

The teen scanned a Florida Lottery Ticket, then, using Photoshop he manipulated the date and numbers. “I’d find someone reading a newspaper at a Starbucks or a sidewalk restaurant and ask them ‘Can you check yesterday’s Play Four numbers?’ They’d rattle them off and I’d ask ‘Do I get anything if I’m close?’…”

The mark would look at the teen’s ticket and see that he had three out of the four winning numbers—a payout of anywhere from $800 to $1,200. “I was only sixteen, but I looked like I was twelve. So I’d tell the mark I was too young to cash the ticket, however… I was willing to give it to them, for half.”

Sometimes they’d say, “I don’t think so kid” or “No, something’s not right,” but most of the time the marks fork over the cash. “I ran the split ticket scam, on and off, for years… It kept me in Nikes and hamburgers.”

BY THE TIME BOSEAK GRADUATED high school there was a warrant out for his arrest on a petty theft charge and a juvenile missing persons report; filed by the staff at one of the shelters he refused to stay at. “My father worked for GM in Detroit and he’d been begging me to take a job at the plant. To get off the street… One day I was sitting on a bench and my tank went dry. All the things that had made life on the street so appealing just vanished.”

Boseak called his father that night and told him “I’ve had enough.”

BOSEAK WORKED on the assembly line at the Big Steel Division of General Motors; along with over 1,000 other factory workers, combining, gluing, and welding together ready-made parts along a series of conveyor belts—making Cadillacs.

He was eighteen-years-old living in a trendy loft, and driving a new heart-pounding 260 horsepower, black Cadillac CTS. “My brother Chris and I were actually in my CTS when he first mentioned ‘carding’ to me,” he says. Chris and his friends were buying credit card information from several websites and using the info to purchase electronics online. “But I didn’t want anything to do with it.” He had a great job and a sweet place to live. “I was done with crime.”

Then in December 2004, the line slowed down. By January 2005, Big Steel started cutting jobs. Boseak had been with GM less than two years, so logically, his position was among the first wave to be eliminated.

That’s when he called his brother and said, “Tell me about carding.”

THERE WAS A LARGE UNDERGROUND world of cybercriminals—hackers, scammers, fraudsters, and counterfeiters—working in conjunction with one another. Carder.net, DarkMarket.com, and CardersUnion.org had gobs of tutorials on different scams, step-by-step instructions on how to scam: Western Union, eBay, PayPal, and on and on. But the bulk of the websites were dedicated to defrauding banks through a variety of credit card frauds.

These international cyber scammers bought and sold “CVV2s*,” “dumps**,” and “fullz***.” The “carding forums” were the equivalent of the Super Walmart of fraud; selling everything from “plastic” to fake IDs; scammer software to carding equipment.

* Footnote: The physical information on the credit card: the card holder’s name, card number, expiration date, and the actual CVV2—the three digit security number of the back of the card

** Footnote: The information encoded on the magnetic strip located on the back of the credit card; consisting of the card holder’s name, card number, bank number, expiration date, and the CVV1—the encrypted security number known only to the bank

*** Footnote: A stolen identity’s full name, DOB, social security number—and in some cases the identity’s credit card info and billing address

They communicate through VPN (Virtual Private Network) servers, that mask their IP (Internet Protocol) address; or socket proxies, which bounce the IP address from one computer to another. Then there’s private messaging and ICQ chatting; all of which make the scammers virtually anonymous.

Using the handle “305scammer*,” Boseak purchased ten CVV2s for twenty dollars and started “virtual carding”—purchasing products online and shipping the merchandise to “drop addresses.” However, he quickly graduated to “in-store carding.” Whereby Boseak would order dumps, use an MSR206 reader/writer to encode the credit cards with the info, then physically enter stores and go on shopping sprees. “My brother and I started off encoding the back of gift cards… and buying Sony Playstations, Nintendo Game Cubes and Microsoft Xboxes, iPods and iPads and gobs of games,” says Boseak. “Then we’d put everything on Craigslist, get stoned and spend the rest of the day playing Hit Man and Metal of Honor.” Customers Western Union or Money Gram’ed them the cash.

* Footnote: 305 is the area code for Miami

Boseak began mastering a variety of scams by reading tutorials on multiple sites; fine-tuning his knowledge of retailers’ credit card fraud security procedures and red flags.

He met “Melmoman,” the author of several tutorials on multiple sites; the two developed a friendship and the veteran scammer introduced Boseak to a Russian vendor, selling quality plastic and fake IDs. Before long Boseak and Chris were carding high-end department stores for big-ticket items. In a single day the siblings hit a dozen department stores for a total of over $100,000. “My loft was wall-to-wall Calvin Klein jeans, Canali dress shirts, Citizens and Movado watches…”

IT’S A HORRIBLY EMASCULATING feeling to be scared of your girlfriend. According to Boseak, he’d managed to get involved with Brittney Baron, a voluptuous, blonde bombshell “model” for the website CollegeGirlsGoneWild.com**. She was serial killer crazy and by early 2005 she’d figured out her boyfriend was carding. “Brittney started blackmailing me,” laughs Boseak. “It started small, but eventually I was giving her a thousand bucks a week to keep her mouth shut… and buying her whatever she wanted.”

** Footnote: No affiliation with Girls Gone Wild

In May—after a huge fight, where Brittney threatened to call the cops regarding his carding operation—Boseak grabbed $30,000 and fled Detroit for Miami.

He entered the Art Institute and immersed himself in courses on: Graphic Illustration, Digital Image Manipulation, Dimensional Design, etc.

In June 2006, he was caught in Galleria Mall trying to use a counterfeit Platinum Visa to buy a $4,500 Rolex. The rent-a-cops placed the wiry twenty-one-year-old in a small room in the security office.

“They handcuffed me to this steel loop bolted to a table and left me,” Boseak tells me. He knew the police were en route. The security guards had taken the counterfeit card and fake ID but they didn’t have his name. “I glanced around the room and stopped at the drop-ceiling… I pushed the cuff up to my palm, squeezed my hand through the shackle, and slipped it off.”

He knew the hallway was on the other side of the holding cell’s wall. So, Boseak climbed onto the table, lifted one of the rectangular ceiling-panels and pulled himself into the three-foot-space. He crouched on top of the aluminum stud wall and used his Cadillac’s ignition key to cut a two-foot hole through the drywall. Several minutes later Boseak dropped down into the hallway and took off; escaping minutes before the police arrived.

His near arrest solidified the fact that, someday, he was going to prison. “At five-foot seven-inches and one hundred-and-thirty-five pounds, I couldn’t fight my way out of a wet paper bag,” admits Boseak. In addition, he possessed fair skin, blonde hair, and blue eyes, “features I feared certain inmates might find appealing. The kind of convicts that like to cuddle and don’t take no for an answer.”

He decided to toughen up his image by getting some serious ink laid down. Boseak wasn’t sure what he wanted when he walked into the tattoo-parlor. He told the tattoo artist he wanted to be taken seriously, “Think gangster.”

Boseak squeezed his eyelids shut and tightened his jaw as the artist ran the needle across his skin, puncturing and inserting the indelible color into his neck. When Boseak emerged from his inky baptism, he was covered in a jumble of precise designs and pictures; a cacophony of harsh Scandinavian deities and villainous Asian mythological creatures.

Prior to his metamorphosis, people seldom noticed him, he tells me. A homeless teen. An unemployment statistic. “Up to that point in my life, I’d been invisible.”

AFTER GRADUATING from the Art Institute in 2007, with a degree in Graphic Design, Boseak straightened up. He got a job as a graphic designer and a steady girlfriend. However, within a year, the economy was in free-fall. Businesses were closing down and unemployment lines were filling up. Boseak knew it was only a matter of time before he was out of work.

In June, Boseak’s brother moved to Miami. The two started carding department and electronics stores, from Ft. Lauderdale to South Beach.

On August 31, the siblings were in Walmart’s electronics department buying iPod accessories when the clerk glanced nervously at Chris and reached for the phone. Boseak looked at his brother, gave him “the nod,” turned toward the front of the store, and started walking. “I raced by the Walmart greeter,” says Boseak, “glanced over my shoulder and noticed Chris wasn’t there.”

As he stepped through the glass and aluminum automatic doors, Boseak heard the slapping of panicked feet on linoleum. Simultaneously, Chris screamed, “Run!” and blew by him as several rent-a-cops emerged out of the store.

They were on top of Boseak immediately. “Come here!” huffed one of the security guards and he grabbed Boseak’s shirtsleeve. He twisted to the left, yanked away, and bolted across the parking lot—losing the guards.

His brother wasn’t so lucky. Chris’ flip-flop blew out, and he stumbled to the asphalt. A fat guard dove on him and pinned Chris to the ground. Boseak bailed his brother out the next morning. Not wanting to face a possible prison sentence, Chris grabbed $20,000 and took off back to Michigan.

“My girlfriend insisted I stop carding.” According to Boseak, while researching opening his own brick and mortar graphics design company he came across a used Fargo HDP 5000 PVC printer on eBay for around $7,500. “It was the sexiest thing I’d ever seen.”

Within weeks Boseak had an Ariic auto-embosser, an AmStamp hot foil tipping machine, several MagTec MSR206 reader/writers and of course…the Fargo 5000.

“The real challenge wasn’t the mechanics,” Boseak explains, “It was the art. The graphic design of the cards and the security features.” Many of the bank logos had to be created in Photoshop. By far, the most difficult security feature was the embedded multi spec foil holographic image of Visa’s dove and MasterCard’s double globes. “After two days of scouring the Internet, I realized no one in the U.S., Canada, or Europe would make them. I was told ‘It’s illegal’ over and over.”

Boseak eventually found a Chinese fabricator on Alibaba to duplicate the holograms. “I don’t even think the Chinaman knew what he was making or why.”

He spent weeks designing dozens of logos and eventually all 50 states driver’s licenses and IDs. “It was an exhausting process.”

BY EARLY 2008, Boseak had established “USplastico” as one of the most credible plastics vendors in the cyber underground. He was on multiple carding forums, including the Russian-led Carder.su—the largest market place for compromised credit card data, counterfeit credit cards and IDs.

His minimum order was fifty pieces: twenty dollars for a blank and thirty dollars for an embossed card. Three hundred dollars per driver’s license or ID. Clients paid via Western Union or Money Gram—specifically due to their anonymity. However, eventually he opened a corporate account with Bank of America using the name Ryan Pearson—one of Boseak’s many false identities.

“I was making around thirty-to-forty grand a month,” says Boseak. He was shipping thousands of cards around the world—from Canada to Serbia. “It was more money than I’d ever seen.”

BOSEAK WAS RESTING in a big cushiony chair inside Barnes & Noble when he received an ICQ from “ShoulderSurfer,” a Russian that Melmoman had recommended him to. He wanted 5,000 Visa and MasterCards. Boseak had never heard of anyone ordering that many pieces. His largest order to date had been two hundred cards.

When the $100,000 wire appeared in his Bank of America account, Boseak says he screamed, “I’m rich bitch!”

Melmoman later explained that ShoulderSurfer worked for the Russian mob running teams of carders throughout Europe.

The day ShoulderSurfer received the cards he made a second order for 5,000—half blank and half encoded. A total of $125,000 worth of cards. Then another order came in, and another.

“The orders were no joke,” Boseak tells me. They required the plastics counterfeiter to design templates for dozens of European banks. Boseak had to order a second Fargo to keep up with the volume coming off the assembly line. “The money was amazing, but I was working eighteen hour days.”

By January 2009, Boseak had two high definition printers churning out over 10,000 pieces of plastic per month. USplastico’s Bank of America account had approximately one million dollars in it. He had almost $200,000 broken up between a couple dozen Western Union prepaid debit cards and another $100,000 in cash, stuffed into several Nike shoeboxes.

“Why quit a good thing?” replies Boseak, when I suggested he walk away. “I loved what I was doing. The smell of the ink, the feel of the warm plastic, the look of the finished product.”

SINCE ITS INCEPTION the U.S. Secret Service has been responsible for maintaining the integrity of the nation’s financial infrastructure and payment systems. As a result, literally every crime Boseak was committing fell under their jurisdiction.

To make matters worse, as Boseak filled orders, the Secret Service was conducting “Operation Open Market.” The largest undercover investigation of a carding forum since the FBI busted CardersMarket in 2007. Open Market’s sole purpose was to dismantle the Russian-led criminal forum Carder.su and arrest its administrators, members and vendors. According to Boseak, it didn’t take long before they became aware of USplastico.

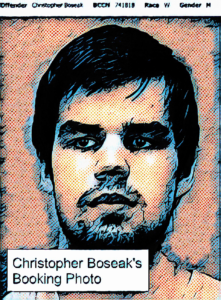

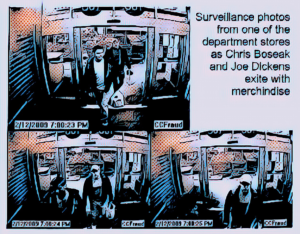

WHILE BOSEAK WAS BUSY CRANKING OUT plastic in Florida, his brother—now a fugitive—was up in Michigan running them up. Chris and a buddy, Joseph Dickens, were carding department stores all over Detroit—buying up accessories for the newest electronics and Xbox video games—and making a killing. Then, on February 12, 2009, the two were arrested after purchasing over $4,900 on a counterfeit Visa.

The officer recovered Chris’ fake ID and nearly two-dozen pieces of plastic.

Boseak tells me, he was working on the design for a Norwegian Bank when his mother called. “She bitched me out, like it was my fault Chris got arrested.”

Within a month Christopher Boseak was sentenced to six months in both Michigan and Florida—to be run concurrent—followed by two years of probation. Once Chris was released, he straightened-up, got a job and quit carding.

OCCASIONALLY, UPS and FedEx packages leaving the country got seized by Customs. “I wasn’t worried about them leading back to me,” says Boseak. He randomly dropped the parcels off at one of the hundred-plus UPS and FedEx drop-boxes scattered throughout Miami. Boseak used the bogus names of obscure pop culture villains like Anton Chigurh from No Country For Old Men or Jason Voorhees from Friday The 13th and American Psycho‘s Patrick Bateman. “Nothing led back to me.”

Eventually to trick Customs—Boseak set up multiple websites and answering services to computer parts refurbishing companies that didn’t exist. The cards were placed in wireless router cases, shrink-wrapped in clear plastic, and accompanied by corresponding invoices to one of his phantom companies. “Customs wasn’t a problem after that.”

TYPICALLY when conducting business Boseak logged onto the internet using a wireless wi-fi antenna—roughly the size of a large salad bowl—with a range of a quarter-mile. He’d tie into a neighbor’s wi-fi connection, thereby virtually eliminating law enforcement’s ability to pinpoint his exact location. He then connected to a VPN server, which masked his (or the neighbor’s) IP address. Once that was done he’d jump on his ICQ account—which was encrypted—and he was free to communicate with USplastico’s customers.

At one point however, the VPN server Boseak was using went down for several days. Instead of finding another VPN provider he continued logging into his ICQ account.

Days later, Boseak pulled into the apartment complex where he lived with his girlfriend; and noticed two Broward County Sheriff’s deputies and two other law enforcement types banging on doors.

The way Boseak tells it, he was stopped by a middle-aged, square jawed suit with a swathe of premature platinum white hair. According to Boseak, Secret Service Agent Dietrich Stortz* asked Boseak for his ID “and he wanted to know if I had a computer. I said, ‘Nope, never liked ’em.’… That was it.”

* Footnote: Name has been changed

Boseak didn’t make the connection between the VPN’s server going down and the Secret Service until days later. He was sitting in Barnes & Nobles’ art section “arguing with a customer over ICQ for… hours. I got up to grab a raspberry slush when I noticed several Miami-Dade Sheriff’s deputies and Secret Service agents headed straight for the front entrance,” says Boseak. Then he caught a glimpse of Stortz’s white hair and realized the VPN server had been compromised. “The most likely explanation was the customer I’d been arguing with was an agent trying to keep me online; allowing the Secret Service to track me to Starbucks’ wi-fi address.”

Boseak whipped around and exited the cafe, just as the officers walked in. They immediately began asking everyone with a laptop for their ID. “I scrambled back to the stacks and snatched my laptop off the chair I’d been sitting in; grabbed a large art book, slipped the jacket cover around the laptop, and placed it on a shelf.”

Fearing that Agent Stortz would recognize him; Boseak crouched low between several bookcases until Stortz and a deputy had passed. Then he strolled out of the bookstore. The incident had Boseak so upset, on the way home, he pulled off Interstate-95 and puked in the median. The next day he retrieved his laptop.

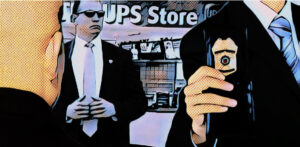

ROCK HILL, SOUTH CAROLINA, wasn’t so much a one-stoplight town as it was a two UPS Store town. There were no drop-boxes of any kind. Boseak and his girlfriend had moved to the city in mid 2009, in the hope of avoiding additional encounters with the Secret Service. Unfortunately, sometime in June, the elderly South Carolinian that worked behind the counter of Boseak’s local UPS Store started asking questions about the tattooed twenty-four-year-old shipping parcels to Russia, Colombia, Ukraine…

On July 3, 2009, Boseak walked into the UPS Store. He didn’t notice the two agents until one of them placed his hand on the counterfeiter’s shoulder and said, “Excuse me, Mr. Pearson?” Both of them were wearing charcoal suits and dark glasses. Average height and weight. “They looked like cliché’s of G-Men. I’d have laughed, had my name actually been Ryan Pearson.”

As it turned out, the elderly South Carolinian had been so curious about Boseak’s international shipments, he’d contacted the U.S. Postal Inspector, and consequently opened one of the parcels. Inside, he found 500 Visa and MasterCards.

The agents patted Boseak down; finding his car keys, but not the Ryan Pearson driver’s license and American Express card, which was sitting in the console of his Cadillac.

“You mind telling us your real name? We know you’re not Ryan Pearson.”

The final scene from the movie Blow flashed into his brain—Johnny Depp, playing George Jung, leaning back in his chair, surrounded by DEA agents—and Boseak knew it was over. “Fuck it,” he said, “Let’s do this… Boseak, my name’s John Boseak.”

They photographed and fingerprinted him in the back of the UPS Store. Then drove the counterfeiter to his townhouse and seized all the equipment in his lab: three laptops, two card printers, four external hard drives, an auto-embosser machine, several reader/writers, and his safe. Which according to Boseak had five hundred pieces of plastic and several miscellaneous cards. “One of which was Pearson’s corporate debit card connected to USplastico’s account—now containing $2.8 million.”

Specifically, regarding the account’s balance, and Boseak’s assertion that the Secret Service took possession of the debit card, we’re relying on Boseak’s word alone as to how the story unfolded. As Boseak tells it, the agents questioned him concerning his status as a Carder.su plastics vendor, but they never mentioned the corporate account.

The agents did suggest he was looking at ten years on the counterfeiting charges; and Boseak had no doubt he’d be facing much, much, more, once the agents discovered he’d provided the Russian mob in excess of 100,000 pieces of plastic, while raking in around $3.5 million. According to Boseak, as the words “ten years” faded from the air, he decided to run.

Shortly after the interview, Boseak was released pending his indictment. Before the Secret Service realized they had an account with several million in it, says Boseak, he drove to the closest Bank of America. “Using my Ryan Pearson driver’s license, I got several cashier’s checks totaling three hundred grand. I grabbed two hundred thousand in cash and a counterfeit driver’s license, social security card, and a Visa in the name Marcus Redding*.” He shoved the Pearson license and credit card into a Nike Air Jordon shoebox—not knowing if he’d ever need them again—and tossed everything in the trunk of his Cadillac. Twelve hours later he was in Miami.

* Footnote: Name has been changed

“I’D ALWAYS WANTED to be a rock star,” says Boseak; and now he was living like one. He was sleeping in a glass and steel skyscraper with tall ceilings, glossy hardwood floors, and amazing views of downtown Miami; he spent nearly two years on an alcohol fueled bender, while partying with the rich and famous; jet setting around the country in a Dassault Falcon 7X and a Gulfstream G-V.

He skied the slopes of Vail, did New Years in Time Square, and shopped on Wilshire Boulevard. Boseak joined the mile-high-club and abandoned half a dozen Cadillacs.

NOT JUST ANYONE can become a vendor on a major carding forum. Typically, vendors need several members or an administrator to vouch for their products and service. Boseak was down to $50,000 by February 2011, and he needed to get back on Carder.su and hookup with ShoulderSurfer.

He contacted Melmoman—who was now an administrator and moderator of Carder.su—however, because he’d disappeared after his arrest, Melmoman refused to allow Boseak back on the site. He’d devastated ShoulderSurfer’s European operation and left dozens of members’ orders unfilled. 305scammer: There has to be something you can do.

Melmoman: I’m willing to send some plastics business your way. And I’ll ICQ ShoulderSurfer and try and clear your name. But that’s it.

That night Boseak ordered the necessary counterfeiting equipment to put together a solid print shop. For extra money, he took on several “cash-out” partners**. True to his word, Melmoman shot him a dozen orders over the next few weeks and Boseak started churning out the cards.

** Footnote: An agreement between two scammers, whereby one provides encoded credit cards and IDs, and the other provides in-store carding services.

While the counterfeiter was shipping plastic around the world, the Secret Service was closing in. On August 17, 2011—based on Boseak’s arrest at the UPS Store in Rock Hill—a federal grand jury indicted him on three counts: possession of counterfeiting instruments and devices, wire fraud, and aggravated identity theft. Days later a warrant was issued for his arrest.

FINALLY! IN SEPTEMBER, Melmoman cleared Boseak’s name with ShoulderSurfer. Between the Russian, his cash-out partners, and a Carder.su vendor he was doing subcontract work for, Boseak says, he was “busy as fuckall.” To hear the counterfeiter tell it, his days consisted of sweating his ass off in his lab, while popping freshly printed Visa, MasterCard, and American Express cards into the hot foil tipping machine and burning the multi spec holograms into their PVC. Once that was done he’d slap them into the embosser and swipe the cards through a reader/writer, encoding each with a different Track. All of this was happening as both printers hummed away, spitting out plastic, while three box-fans struggled to circulate cool air over the state-of-the-art equipment.

As quickly as the money came in, Boseak transferred it onto dozens (what ultimately became over one hundred and fifty) of prepaid debit cards; all of which had been obtained using batches of anonymous fullzs’ info.

ON JANUARY 10, 2012, thirty-nine individuals connected with the Carder.su organization were indicted for participation and conspiracy to engage in RICO (Racketeer Influence Corruption Organization), trafficking in, and production of, false identification documents.

The name John Boseak wasn’t among the defendants… however, the indictment did include eleven John Does.

THE AMOUNT OF PACKAGES Boseak was shipping began to worry him. He widened the drop locations from Miami to Ft. Lauderdale, West Palm Beach, Coconut Grove, etc. Pushing the circumference outward, in the hope that the Secret Service wouldn’t be able to pinpoint his location. At regular intervals, Boseak would charter flights around the country to drop off packages and do a little partying.

In early 2012, he exited a private jet and stuffed four parcels into a FedEx drop-box at Vegas’ McCarran International Airport—three destined for eastern Europe and one for Canada—all were shipped using the name Keyser Soze.

While Boseak spent the weekend at the Palms with a stripper he’d met at Spearmint Rhino Gentleman’s Club, the eastern European parcels passed through Customs without incident; however, something sparked an inspection of the Canadian bound package. By the next morning Customs had discovered two hundred encoded credit cards and four North Carolina Driver’s Licenses. With help from FedEx they tracked the parcel’s origin back to the airport and requested assistance from the Clark County Sheriff’s Office.

Cool air rushed over Boseak and the stripper as they stepped into the terminal. Boseak immediately noticed the deputies standing near the private charters’ counter. “Mr. Redding!” barked one of the officers, “we need to talk to you.”

He was escorted to a windowless area reserved for private charters’ administration. “They wanted to know why I’d used an alias to mail the parcels,” says Boseak. His foot was bouncing like a jackhammer. “I told them ‘Those weren’t even my packages, my buddy Keyser asked me to drop ’em off.'”

The deputy scoffed and informed Boseak that Keyser Soze was the name of the villain in the movie The Usual Suspects. Then he leaned forward, keeping his eyes locked on Boseak’s, and growled, “But I think you know that…”

The deputies ran the name Marcus Redding—the name that appeared on Boseak’s counterfeit Alabama Driver’s License—through NCIC. Miraculously, nothing showed up. “They took my info—my Redding info—and told me I’d be hearing from Customs. But everything was fake… so, I never heard from anyone.”

ON MARCH 6, 2012, Secret Service agents throughout the country began a series of raids on the twenty-eight Operation Open Market defendants unlucky enough to be living in the Unites States. The agents kicked in the doors of nearly a dozen hackers’ and counterfeiters’ homes. They pounced on another half a dozen unsuspecting fraudsters and carders in mall parking lots, department stores, and in the driveways of their own residences. In addition, the agents manufactured ploys to lure the eleven indicted John Does into ambushes.

The way Boseak tells it, BeastiMan*—a part-time cash-out partner, he’d been working with for over six months—ICQed: I’ve got a Carder.su vendor that wants to sell 40,000 multicolored PVC cards [four boxes containing 10,000 cards] for $300. Do you want them?

* Footnote: Name has been changed

305scammer: Fuck yeah, I want them! Send me payment instructions and I’ll get you an address.

Boseak trusted BeastiMan enough to send his vendor three hundred dollars in Bitcoins, but not enough to give him his home address—where he now lived with his new wife, Rosalia. Instead, he obtained an address from Brickell Bayview HQ—a company specializing in virtual office administrational support for transient businesses.

While standing in the Brickell elevator, crowded with businessmen wearing expensive suits, Boseak noticed a square jawed man in the reflection of the stainless steel doors. Secret Service Agent Stortz—the same agent that had almost grabbed him in a Barnes & Noble years earlier—with his swathe of premature platinum white hair, was standing two suits behind him.

Instantly Boseak knew the UPS packages were a setup. A wave of heat enveloped him. Stortz however, didn’t seem to notice the counterfeiter. The elevator pinged, the doors whirled open, and Boseak exploded through the opening; rushed past HQ’s office and stepped into a law firm down the hallway.

“HQ was located directly in front of the elevators,” says Boseak. In a stroke of luck, a courier stepped into the law firm. “I paid the guy to pickup the UPS parcels.” As the courier retrieved the packages from HQ’s receptionist, Boseak slipped out of the law firm and into the elevator. “I remember being disappointed Stortz hadn’t confronted the courier in HQ.”

By the time Boseak exited Brickell Bayview, he’d decided his sighting of the Secret Service agent had been a coincidence, and completely unrelated to the delivery. So he decided to wait for the courier and retrieve the packages.

“He exited the lobby with the UPS boxes and before I could approach him, Stortz and two other agents came from out of nowhere—with their weapons drawn—yelling, ‘Secret Service! Get on the ground!’ They cuffed the courier and dragged him off.”

By March 22, the Secret Service had arrested nineteen of the Operation Open Market defendants. Nine of the John Does had eluded them. Boseak doesn’t know if Melmoman was one of them, but he never spoke with him again.

On November 30, Boseak’s luck ran out. He and his wife were pulled over by the Temple Terrace Police. As cruisers and officers surrounded their Cadillac, Boseak turned to his wife—knowing he was about to be arrested—and said, “The first thing they’re gonna do is go to our townhouse and search it. (Rosalia’s eyes widened slightly. Her husband’s entire counterfeiting lab was sitting in their house.) Get rid of everything.”

It wasn’t until Boseak was brought before a judge that he learned he’d been arrested for his South Carolina counterfeiting charge and not Operation Open Market. He was released on bond a week later, on the condition he’d report to the probation office, and submit to regular drug testing.

“When I got home I noticed the counterfeiting equipment was gone. I asked my wife where she’d put it… She said, ‘I got rid of it… I threw it away.'”

Rosalia had paid two of their neighbor’s kids to drag over $30,000 worth of counterfeiting equipment to the complex’s dumpster. “What about the cards?!” snapped Boseak, in a fit of panic. “The Western Union cards?!” containing nearly all his illicit funds.

“You said, ‘get rid of everything…'” Along with around 10,000 multicolored PVC cards she’d thrown out over 150 prepaid debit cards, containing a combined total of over one million dollars; and she’d gotten rid of his laptop…with all the fullzs’ info on it.

“Oh my fucking God!” There was no replacing the cards. The money was gone.

BASED ON THE FEDERAL Sentencing Guidelines Boseak’s attorney informed him he was facing between eight to ten years. Plus, two extra-years for aggravated identity theft. She told him he needed to prepare himself for the very real possibility he’d be spending the next decade in prison.

Things were looking bleak. Boseak started smoking weed all day and drinking excessively. Then, on February 1, 2013, he failed a urinalysis test. Three months later, he was arrested by the U.S. Marshals and transported to Lexington County Jail, South Carolina.

According to Boseak, in the summer of 2013, his attorney showed up at the jail with a plea agreement. “Just before I signed,” he says, “I said something about the nosy old man at the UPS Store and my attorney asked, ‘What old man?'” Boseak explained how the elderly South Carolinian had opened the parcel and found the plastic.

“I thought the Secret Service had a warrant?”

“I don’t think so…”

She quickly gathered up her things. “I’m going to check on something,” she said, “and I’ll get back with you.”

A week later the lawyer was back. As a result of the warrantless search, she’d convinced the U.S. prosecutor to drop the possession of counterfeiting instruments and devices, and wire fraud charges. “I got you two years on the aggravated identity theft.”

A week before his sentencing Boseak’s attorney and two Secret Service agents showed up to talk. “I thought, This is it, they’re gonna ask me about Ryan Pearson’s corporate account with the $2.5 million and the $300,000 I took off with… But they never did.” It was much worse. The agents wanted to know about Boseak’s time as a vendor on Carder.su. How long had he been on the website? Had he ever been to Russia? Did he know any of the other vendors or administrators? Boseak told the agents he hadn’t been on the site since his arrest in 2009.

“We know you were on the site as recently as last year,” snorted one of the agents.

“No,” sputtered Boseak, as acid flooded into his stomach and he fought the urge to vomit. “No, that’s not true.”

“I think you’re lying. I think you’re one of the John Does we’ve been looking for—”

At that point Boseak’s attorney stopped the interview.

September 11, 2013, John Boseak was sentenced to twenty-four months; to be served at the Federal Correctional Complex in Coleman, Florida. That’s where I met him.

AT THE TIME, IT APPEARED that Boseak had lost the money, his wife, and his freedom, while managing to dodge the Operation Open Market indictment.

“There’s no evidence,” he says, when I asked if he was worried about the Secret Service. “I’m probably not one of the John Does anyway…” Then, a mischievous grin tugs at the corners of his lips and he almost whispers, “You know, the greatest trick the Devil ever pulled was convincing the world he didn’t exist;” quoting Kevin Spacey’s iconic role as Roger “Verbal” Kint, aka Keyser Soze, from the movie The Usual Suspects.

The recidivism rate for white-collar criminals is high—somewhere around thirty percent—and for a career cyber scammer like Boseak… well, there’s no ceiling. “What’re your plans for the future?”

“I’m going straight,” he replies sincerely. “It’s not like I can’t do somethin’ else. I’m not irrevocably bent. I can straighten up.” I’m almost convinced until he chuckles. “Of course… they never did find that money.”

Based on our interviews, I knew the Ryan Pearson license and credit card were tucked inside a Nike shoe box; and that box was sitting with the rest of Boseak’s clothes, safely stored in his soon-to-be-ex-wife’s parents’ spare room. “You think the money’s still there?”

“If things don’t work out for me on the street… I’m sure as shit gonna find out.”

In early October 2014, Boseak was released to the Dania Beach Halfway House in Ft. Lauderdale, Florida. During the writing of Bent we emailed constantly and spoke on the phone several times a week. Sometime in April 2015, I called his cell. There were voices in the background. I asked where he was and he said, “I’m at the mall.”

“What’re you doing at the mall?” I knew he didn’t have any money. Despite working full-time, plus overtime, it had taken Boseak five months to save the $2,000 necessary to rent an apartment in Overtown—one of Miami’s roughest neighborhoods. It was my understanding that things had not been working-out for him.

He laughed. “I’m just doin’ what I do, bro.” He was carding and I knew, soon, he’d be counterfeiting. I warned him to be careful. Not to get arrested.

“Don’t worry about me, just keep writing.”

Within a month he’d stopped returning emails and answering his phone. By August his cell had been disconnected. I can’t tell you why he broke contact, but if I had to venture a guess, I’d say that sometime in the summer of 2015, Boseak stepped into one of the many pristine branches of Bank of America in the greater Miami area. He placed his Ryan Pearson driver’s license and American Express card on the counter, and asked the teller to check the status of his corporate account.

She glanced at the photo on his license and shot him a polite smile. I like to think her eyes lingered over the tattooed images that covered his arms and neck, and asked, “Are you someone famous… like a rock star or someone?” Regardless, I’m fairly certain Boseak walked out of that bank with a cashier’s check for over $2.5 million.

That’s what I think happened. What I know happened, is that in July 2015, John Boseak stopped reporting to his federal probation officer. By October 2, 2015, the court had issued a warrant for his arrest, and at this very moment the U.S. Marshals are looking for him.

Roughly around the same time I was wondering if he’d risked it all and gone for the money, I received an email through a mutual friend that simply read: I’ve spoken with your boy Ryan P… He’s alive…